What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

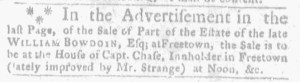

“In the Advertisement in the last Page … the Sale is to be at the House of Capt. Chase, Innholder in Freetown.”

A correction to an advertisement that appeared on the final page of the February 3, 1774, edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter appeared on the second page. It advised, “In the Advertisement in the last Page, of Part of the Estate of the late WILLIAM BOWDOIN, Esq; at Freetown, the Sale is to be at the House of Capt. Chase, Innholder in Freetown (lately improved by Mr. Strange) at Noon, &c.” The original advertisement stated that a tract of land “is to be Sold at the House of Mr. Strange, Innholder in Freetown.” The revision correctly acknowledged that Chase now occupied and operated the inn formerly belonging to Strange. Bowdoin’s executors likely also hoped that it prevented prospective bidders from missing the sale if they went to Strange’s current establishment instead of Chase’s house.

Why not avoid that confusion by updating the advertisement itself? The answer to that question requires knowing more about the process of producing newspapers on manual presses in the eighteenth century. Weekly newspapers usually consisted of four pages created by printing two pages on each side of a broadsheet and then folding it in half. Printers typically printed the first and fourth pages first. As the ink dried, they set type for the second and third pages. That meant that the newest or more significant content did not necessarily appear on the front page! Instead, advertisements sometimes filled the first and last page, with news items and editorials on the center pages.

For the February 3 edition, advertisements ran in the first column of the first pages and news received from New York in the other two columns. The estate notice appeared on the final page. On January 27, the first time the executors inserted it in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter, the advertisement ran on the first page. From one issue to the next, the compositor transferred type already set from one page to another. By the time the executors contacted the printing office about the error, it had already been replicated once again. Presumably the first and fourth pages for the new issue had been printed, leaving Richard Draper, the printer, to resort to a separate notice on another page to offer the clarification.

The same advertisement, with the same error, ran in the Boston Evening-Post on January 24. Bowdoin’s executors did not spot the error in time to submit a correction before the January 31 edition, so it appeared once again. That correlates with a correction for the February 3 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter arriving at the last minute to make it into that issue. In the next issue of the Boston Evening-Post, published February 7, the estate notice ran with revised copy. Similarly, the February 10 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Lettercarried the advertisement once again, this time with revised copy. Given sufficient time, printers and compositors did revise advertisements when their customers made such requests. When they did not have time, they deployed other strategies for updating their readers.