What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“EXTRACTS from the Votes and Proceedings of the AMERICAN CONTINENTAL CONGRESS.”

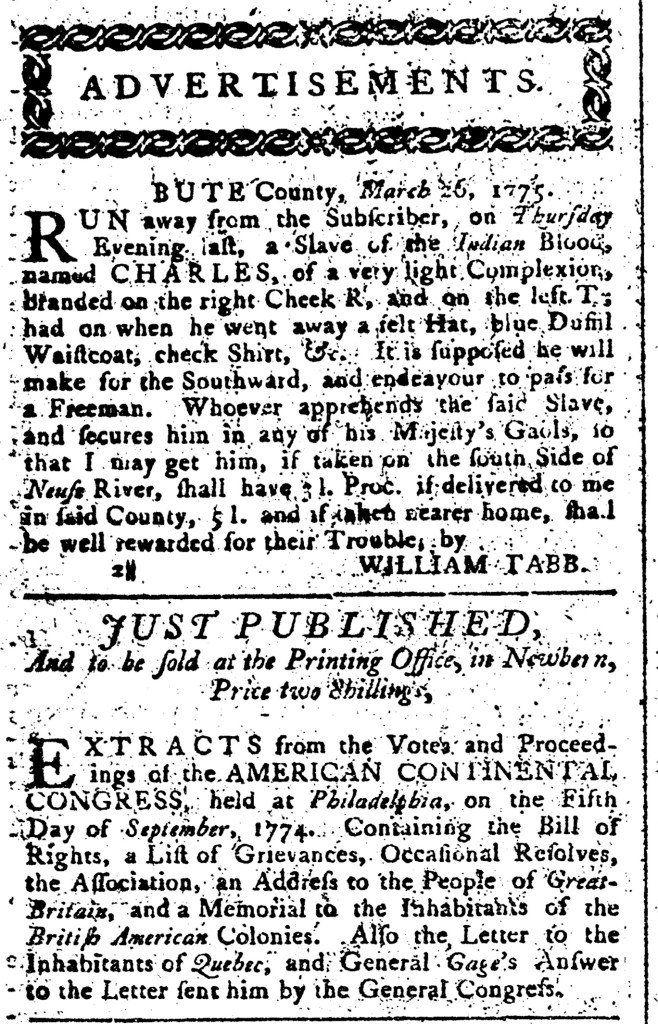

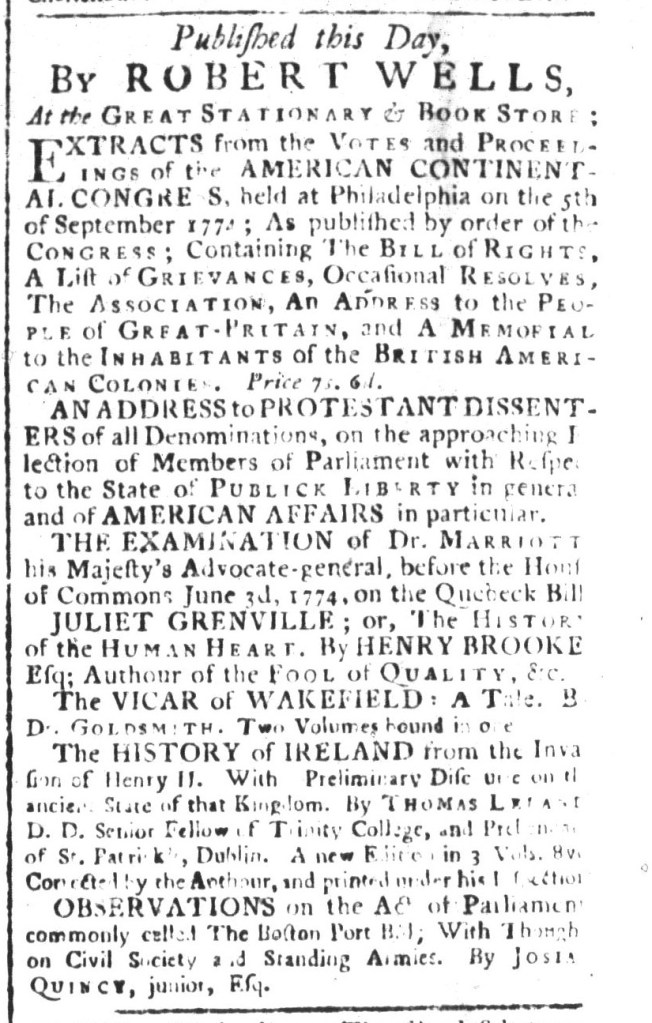

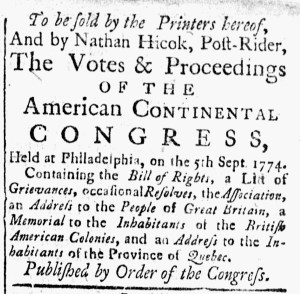

When they perused the July 7, 1775, edition of the North-Carolina Gazette, readers encountered an advertisement that proclaimed, “JUST PUBLISHED, And to be sold at the Printing Office … EXTRACTS from the Votes and Proceedings of the AMERICAN CONTINENTAL CONGRESS, held at Philadelphia, on the Fifth Day of September, 1774.” The Extracts, however, were not “JUST PUBLISHED,” though James Davis certainly had them for sale at the printing office in New Bern. The Adverts 250 Project previously featured this advertisement’s appearance in the April 7, 1775, edition of the North-Carolina Gazette. Few issues of that newspaper survive, preventing a complete reconstruction of when the advertisement ran. Only seven issues, all from 1775, are available via America’s Historical Newspapers, the most comprehensive database of digitized eighteenth-century newspaper. Davis’s advertisement for the Extracts did not run on March 24, but appeared on April 7, May 5, and May 12. It was not in the June 30 issue, yet it returned for the July 7 and July 14 issues.

It is not clear how often the advertisement ran between May 12 and June 30, but Davis did not insert it in the issue immediately before the one that delivered several important updates that might have influenced him to believe that readers who had not yet purchased the Extracts would have increased interest in the “Bill of Rights, a List of Grievance, Occasional Resolves,” and “General Gage’s Answer to the Letter sent him by the General Congress.” The Extractsdocumented the meeting of the First Continental Congress in the fall of 1774. When the advertisement ran on July 7, 1775, the Second Continental Congress had been meeting for nearly two months. That issue included an update that “By Letters from the Congress of the 19th of June, we are informed, that Col. Washington, of Virginia, is appointed General and Commander in Chief of all the American Forces.” It also delivered news of the Battle of Bunker Hill, acknowledging that the account received in the printing office was “very imperfect, and must leave us in Suspence till a further Account of this most momentous Affair arrives.” Indeed, that “imperfect” account inaccurately claimed that “General Burgoyne fell … and was interred in Boston with great Funeral Pomp.” As he sorted through newspapers and letters arriving from the north, Davis apparently believed that the news he selected for publication would spark new interest in his remaining copies of the Extracts from the First Continental Congress.

As had been the case in the April 7 edition, that advertisement ran alongside another that described an enslaved man who liberated himself by running away from his enslaver. In this instance, “a Negro Slave … named JEM,” was a fugitive from slavery who might have been “harboured or kept out by his Wife, named Rachel.” James Biggleston, Jem’s enslaver, suspected that Jem was “lurking in the Neighborhood” of the plantation where Rachel was enslaved. Biggleston offered a reward for the capture and return of Jem in a nota bene at the end of the advertisement, though the main body of the notice consisted of a warrant signed by “Two of his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace” that authorized that “if the said Jem doth not surrender himself, and return home immediately … that any Person or Persons may kill and destroy the said Slave … without Impeachment or Accusation of any Crime or Offence … or without incurring any Penalty.” Most readers of the North-Carolina Gazette and other newspapers compartmentalized the contents of those publications. They did so to such an extent that the juxtaposition of colonizers demanding freedom from oppression and enslaved people seeking liberty did not register as a contradiction.