What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Unfashionable [lace] … taken to pieces and made into fringe.”

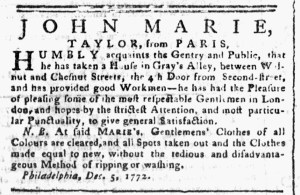

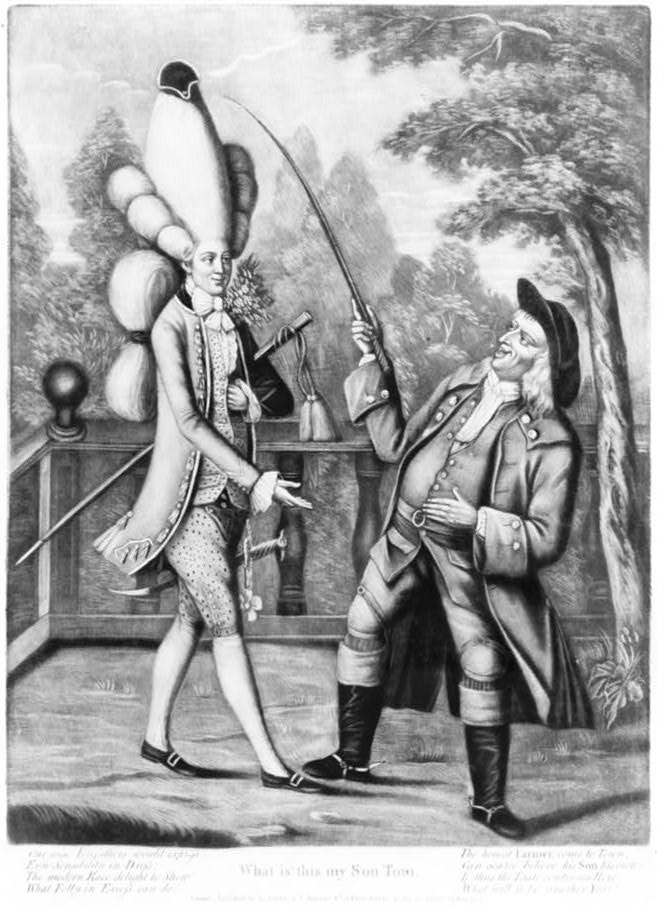

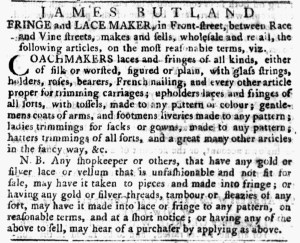

In the summer of 1775, James Butland, a “FRINGE and LACE MAKER, in Front-street” in Philadelphia, placed a new advertisement in some of the city’s newspapers. A few months earlier, he assured “the public, that no advantage shall be taken on account of the troubles between Britain and America” and “he retails his goods cheaper than ever they were in this country before.” In other words, he did not raise his prices for the fringe and lace he made in Philadelphia once the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement adopted in protest of the Coercive Acts, went into effect. In his new advertisement, he reminded readers that he “makes and sells … COACHMAKERS laces and fringes of all kinds … and every other article proper for trimming carriages; upholders [upholsterer’s] laces and fringes of all sorts, with tossels, made to any pattern or colour; … hatters trimmings of all sorts, and a great many other articles in the fancy way.”

In a nota bene that constituted a significant portion of this advertisement, Butland sought other business by proposing an eighteenth-century version of upcycling, the transformation of unwanted or undesirable items into fashionable new ones. “Any shopkeeper or others, that have any gold or silver lace or vellum that is unfashionable and not fit for sale,” he suggested,” may have it taken to pieces and made into fringe.” Furthermore, anyone “having gold or silver threads, tambour or sleazies of any sort, may have it made into lace or fringe to any pattern.” Tambour, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, could have referred to either a kind of fine gold or silver thread or a kind of embroidery that Butland deconstructed for the materials. Sleazies, a corruption of Silesia, referred to a kind of thin woven cloth originally from Silesia and used for making clothing in Britain and the colonies in the eighteenth century. Butland did this work “on reasonable terms, and at a short notice,” promoting both price and efficiency. Even if readers were not interested in incorporating upcycled fringe into their own wardrobes or décor, Butland still wanted any castoffs that they wished to sell to him. With the Continental Association still in place and the uncertainty about when trade with Britain might resume following the outbreak of hostilities in Massachusetts in April, Butland may have needed materials to continue his business.