What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

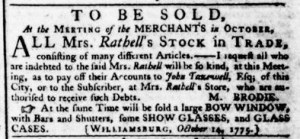

“Will be sold a large BOW WINDOW, with Bars and Shutters, some SHOW GLASSES, and GLASS CASES.”

In the spring of 1775, Catherine Rathell, a milliner in Williamsburg, advertised her intention to “dispose of my Goods” and go to England “till Liberty of Importation is allowed.” The Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement devised by the First Continental Congress in protest of the Coercive Acts, disrupted trade for merchants, shopkeepers, and others who sold imported goods. When she first placed her advertisement, Rathell and the rest of the residents of Williamsburg had not yet received word of the battles at Lexington and Concord. The outbreak of hostilities may have prompted her to adjust her plans because she did not wait until she sold all her merchandise to depart. Instead, she left her wares in the hands of Margaret Brodie, a mantuamaker who had worked with Rathell since 1771, to sell “At theMEETING of the MERCHANTS in OCTOBER.” The milliner did not return to Williamsburg. Unfortunately, she died when the ship taking her to England got caught in a hurricane and sank.

Brodie’s advertisement in the October 14, 1775, edition of John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette concerned more than just selling Rathell’s remaining merchandise. It also called on those indebted to Rathell to settle accounts with Brodie. A short note at the end of the notice, marked with a manicule to draw attention, noted that “a large BOW WINDOW, with Bars and Shutters, some SHOW GLASSES, and GLASS CASES” would be sold at the same time as “Mrs. Rathell’s STOCK in TRADE.” That provides a glimpse of Rathell’s merchandising strategies. By the early eighteenth century, bow windows became popular features of shops in London, so common that some critics complained about the way that they jutted into the street and made it more difficult for pedestrians to pass. Yet that was one of the intended purposes, causing prospective customers to slow down and view the merchandise on display. In addition, bow windows offered more space for displaying goods than windows flush with exterior walls. Some American retailers, including Rathell, adopted this strategy for marketing their wares. Rathell also invested in glass cases to showcase some of her merchandise for visitors to her shop. She could protect valuable items from shoplifters while still making them visible to entice customers. Similarly, the bars on shutters on the bow window protected goods from burglars when the shop was closed. Without contemporary visual images of American shops, Rathell’s advertisement helps reconstruct their interiors and the experience of shopping in eighteenth-century America.