What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

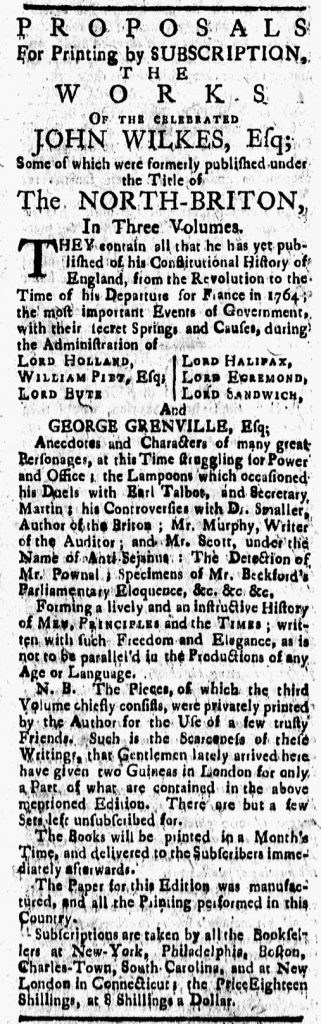

“Subscriptions are taken by all the Booksellers.”

A subscription notice for “THE WORKS OF THE CELEBRATED JOHN WILKES” appeared among the advertisements in the January 13, 1769, edition of the New-London Gazette. The advertising copy exactly replicated that of a notice published in the New-York Journal a month earlier, with one exception. Like other subscription notices, it informed prospective customers where to submit their names to reserve a copy: “Subscriptions are taken by all the Booksellers at New-York, Philadelphia, Boston, Charles-Town, South-Carolina, and at New London in Connecticut.” The previous advertisement did not list New London. It had been added to the subscription notice in the New-London Gazette to better engage local readers.

Whether including New London or not, both versions of the subscription notice invoked the concept of what Benedict Anderson has famously described as “imagined community.” Print culture contributed to a sense of community among readers dispersed over great distances by allowing them to read the same newspapers, books, and pamphlets, all while imaging that their counterparts in other cities and towns were simultaneously reading them and imbibing the same information and ideas. This subscription notice envisioned readers in Boston and Charleston and place in between all purchasing and reading the same book. Anderson argues that imagined community achieved via print played a vital role in the formation of the nation. Wilkes, a radical English politician and journalist, had become a popular figure in the colonies during the imperial crisis. The subscription notice for his works appeared while the Townshend Act was in effect, at the same time that many colonists mobilized nonimportation agreements in protest and the New-Hampshire Gazette was printed on smaller sheets because the publishers refused to import paper from England that would require them to pay duties.

The slightly revised version of the subscription notice had the capacity to even more effectively invoke the idea of an imagined community among colonists. It did not limit the collection of subscriptions to the four largest port cities, the places with the most printers and the most newspapers. Instead, by listing New London with Boston, Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia, the subscription notice expanded the sphere of engagement by making the proposed book more accessible on the local level for readers and prospective subscribers in New London and its environs. Reading Wilkes was not just for colonists in urban settings. Instead, it was an endeavor for colonists anywhere and everywhere.