What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

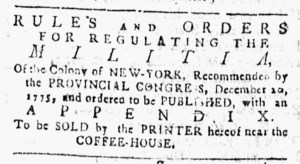

“RULES AND ORDERS FOR REGULATING THE MILITIA, Of the Colony of NEW-YORK.”

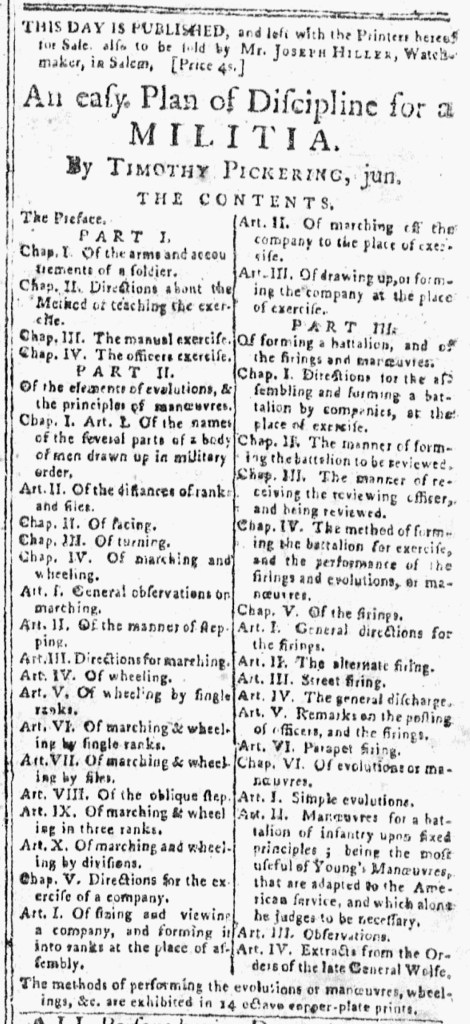

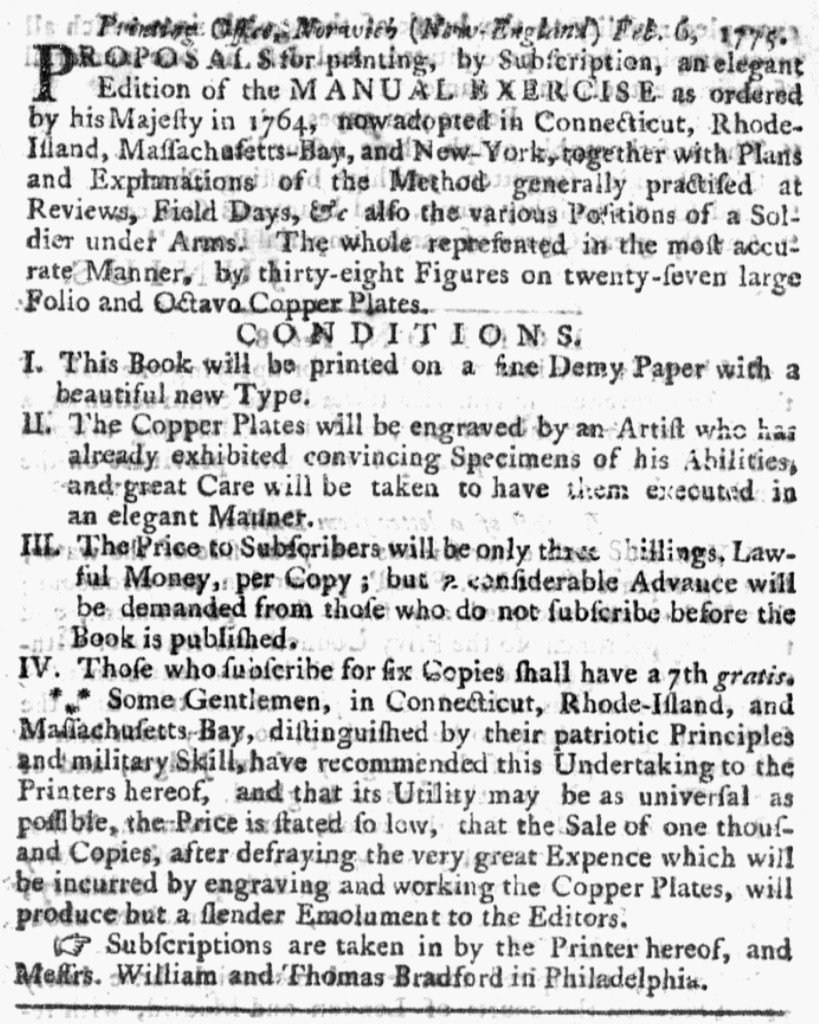

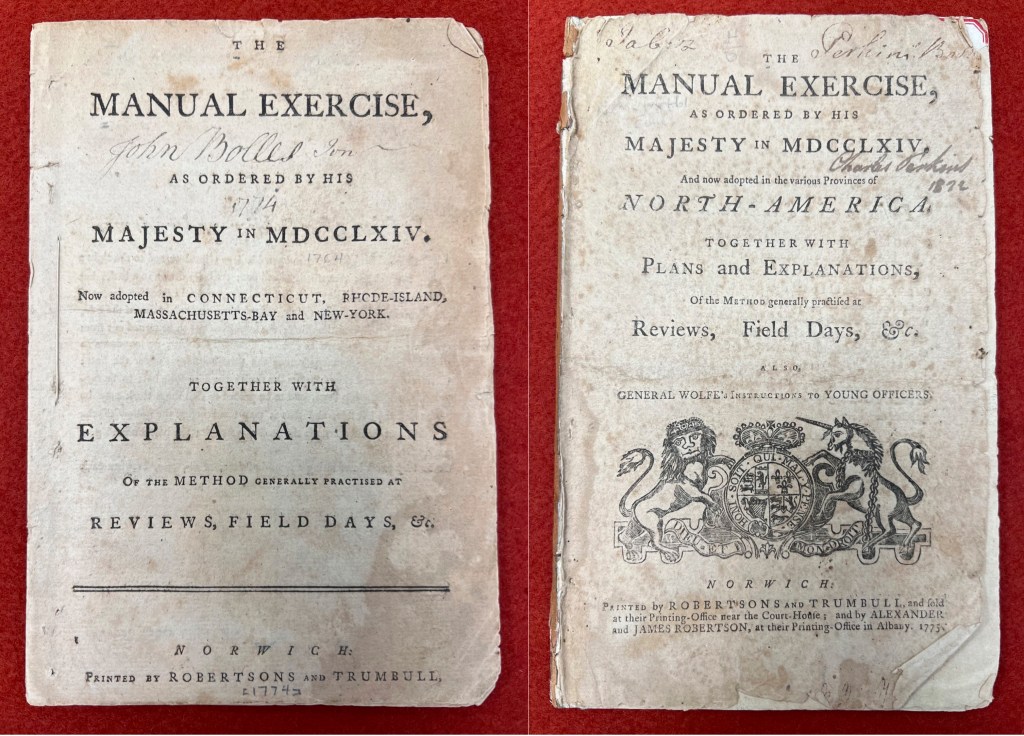

Advertisements for military manuals began appearing regularly in many American newspapers in 1775 and 1776. They appeared most frequently in New England, where the first battles of the Revolutionary War occurred, and in Philadelphia, where the Second Continental Congress met, but not solely in those places. On January 18, 1776, John Holt, the printer of the New-York Journal, ran an advertisement for “RULES AND ORDERS FOR REGULATING THE MILITIA, Of the Colony of NEW-YORK, Recommended by the PROVINCIAL CONGRESS, December 20, 1775, and ordered to be PUBLISHED, with an APPENDIX.”

That pamphlet presents a bibliographical mystery. On September 24, 1775, the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercurycarried the “RULES and ORDERS for regulating the Militia of the Colony of New-York, recommended by the Provincial Congress, August 22, 1775,” filling almost two columns on the first page and spilling onto the second page. By then, Holt had been advertising a twelve-page pamphlet featuring the “RULES AND ORDERS” for nearly a month. His first notice appeared in the August 31 edition of the New-York Journal. He may not have appreciated Hugh Gaine’s decision to disseminate the same content for free, potentially undercutting sales of the pamphlet, yet the pamphlet offered a different format that readers, especially those who had cause the consult the manual regularly, likely found more convenient. Gaine presented information as a service to the public, while Holt packaged the same content for practical use by officers and others.

The advertisements for Holt’s first edition of the “RULES AND ORDERS” did not mention an appendix. That first appeared in his advertisement from January 18, 1776, along with an assertion that the “PROVINCIAL CONGRESS” adopted the “RULES AND ORDERS” on December 20, 1775, rather than August 22, 1775. Had the provincial congress revisited the issue and recommended the same (or revised) “RULES AND ORDERS” after just four months? Or did the new advertisement feature an error in the date? What, if anything, did the appendix contain that was not part of the original pamphlet? Unfortunately, no copy of a pamphlet with a title that includes the date December 20, 1775, survives. Holt regularly inserted advertisements for it in the New-York Journal for three months, suggesting that he did indeed stock such a pamphlet (but not revealing how many he sold). How and whether that pamphlet differed from the first one remains a mystery.