Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Lemuel Gustine, who was committed on Suspicion of counterfeiting New-York Money.”

Advertisements in colonial newspapers often delivered news to readers, supplementing the news that printers selected to appear elsewhere in their publications. Colonizers who perused the September 5, 1772, edition of the Providence Gazette, for instance, learned of the death of Joshua Spooner, “late of Providence, Carpenter,” in an estate notice placed by John Smith. They also found details about lotteries approved by the General Assembly for the purposes of raising funds “to build a Town Wharff in Warwick” and “for the repairing the Meeting House in the Town of Barrington; and also for the purchasing and opening some Highways in said Town.” Another advertisement informed readers that Peter Heynes, “SCHOOLMASTER from DUBLIN,” planned to open an evening school with a term that ran from October 10 through April 10.

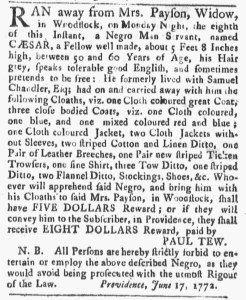

Advertisements also delivered news about crimes and their perpetrators. Paul Tew, the sheriff, ran an advertisement about Lemuel Gustine, who had been committed to “his Majesty’s Goal in Providence … on Suspicion of counterfeiting New-York Money.” That notice previously appeared in the August 22 and August 29 editions. Disseminating news in the form of an advertisement had the advantage of keeping it in the public eye for longer durations. It also reached readers who only occasionally perused newspapers and might have missed an article that ran only once in an issue they did not read. Tew described Gustine, noting both the clothing he wore at the time he made his escape and a distinctive “cut on the Forehead in the Cherokee Mode.” Gustine had been born in Saybrook, Connecticut. The sheriff suspected that he was headed in that direction. No matter where Gustine may have been at the time Tew’s advertisement spread the news of his escape from the jail in Providence jail for the third time, readers in Rhode Island, western Connecticut, and southern and central Massachusetts had access to information about his alleged crime, his appearance, and the reward for capturing and returning the fugitive to the sheriff. Both Tew and the public had an interest in repeatedly disseminating news about criminals via advertisements in colonial newspapers.