What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A TREATISE … on the treatment of wounds and fractures, with a short APPENDIX on camp and military hospitals.”

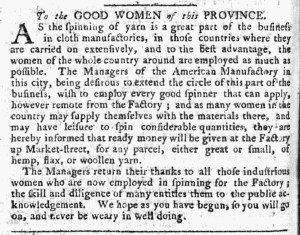

Even before the battles at Lexington and Concord, advertisements for military manuals appeared in colonial newspapers. The number of manuals available to the public and the frequency of the advertisements both increased following the outbreak of hostilities. Yet not all the manuals on the market addressed military discipline and maneuvers. In the December 16, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, George Weed promoted “A TREATISE, entitled plain and concise practical remarks on the treatment of wounds and fractures, with a short APPENDIX on camp and military hospitals, principally designed for the use of young military surgeons, in North-America. By JOHN JONES, M.D. Professor of Surgery, King’s College, New-York.” As was often the case when advertising books, Weed did not generate advertising copy but instead used the lengthy title of the book to promote it in the public prints. He likely sold copies of an edition printed by John Holt in New York. The treatise apparently met with such success that Robert Bell, a prominent printer and bookseller in Philadelphia, decided to publish another edition in 1776.

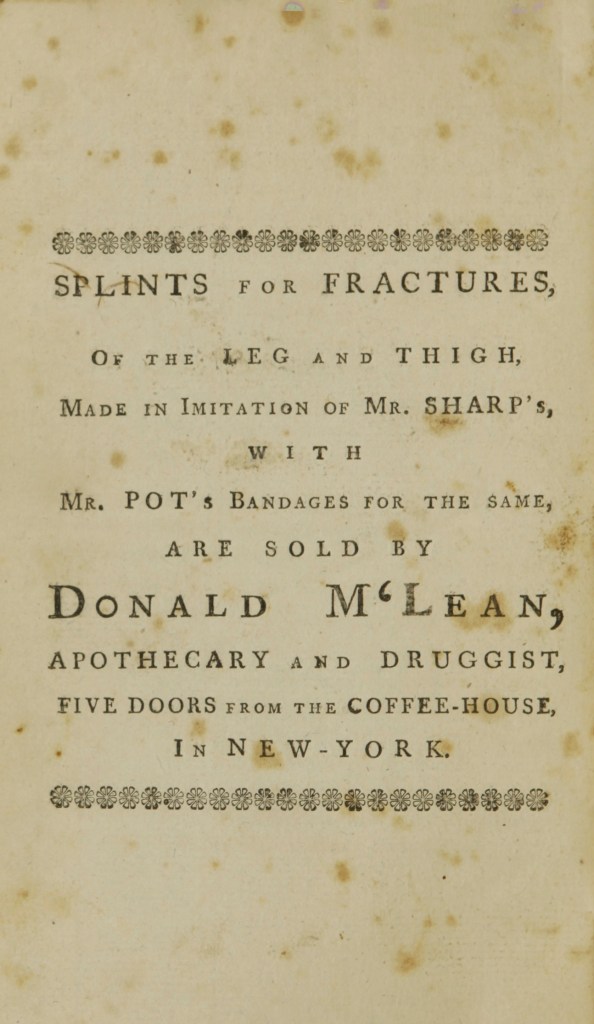

The book itself became a vehicle for distributing additional advertising. Printers and booksellers frequently inserted their own advertisements in books, pamphlets, and almanacs, yet that was not the case with this medical treatise. Instead, it featured an advertisement from a medical practitioner that resonated with the contents of the book. After the treatise and appendix, a full-page advertisement informed readers that “SPLINTS FOR FRACTURES, OF THE LEG AND THIGH, MADE IN IMMITATION OF MR. SHARP’S, WITH MR. POT’S BANDAGES FOR THE SAME, ARE SOLD BY DONALD M ‘LEAN, APOTHECARY AND DRUGGIST, FIVE DOORS FROM THE COFFEE-HOUSE, IN NEW YORK.” Two lines of fleurettes, one above and below, adorned the advertisement. Today, readers expect to encounter promotions for books and related products incorporated into books by publishers, yet that marketing strategy was not invented by the modern publishing industry. Instead, it dates to the eighteenth century and earlier as printers, booksellers, and other entrepreneurs devised many kinds of advertising media. The Adverts 250 Project focused primarily on advertisements that appeared in eighteenth-century newspapers for several reasons, including their abundance and frequency, yet early Americans encountered many forms of advertising, including broadsides, billheads, catalogs, trade cards, and advertisements inserted in books.