What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“I am sorry that I have drank any Tea.”

Ebenezer Punderson had the misfortune of appearing in an advertisement placed in the Norwich Packet by the local Committee of Inspection in the issue that carried the first newspaper coverage of the battles of Lexington and Concord. The committee accused him of drinking tea in violation of the Continental Association, disparaging the First Continental Congress, and refusing to meet with the committee to discuss his conduct. In turn, the committee advised the public not to carry on any “Trade, Commerce, Dealings or Intercourse” with Punderson.

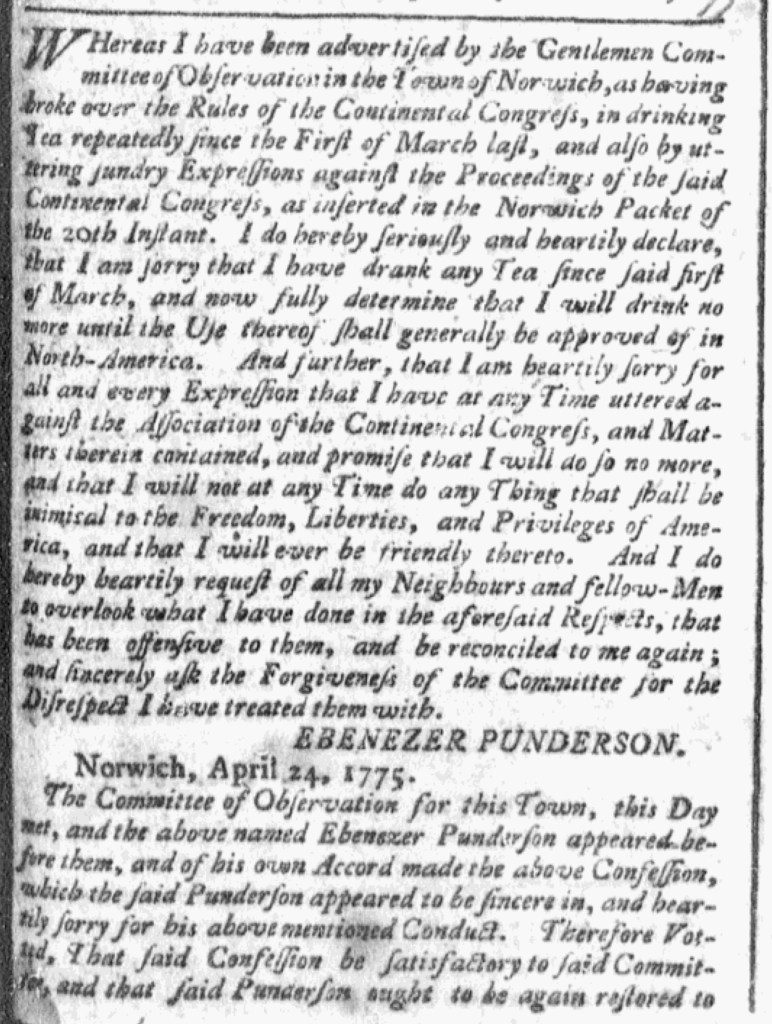

Perhaps Punderson would have weathered that sort of public shaming under other circumstances, but news of events at Lexington and Concord made his politics even more unpalatable and his situation more dire. From what ran in the newspaper, it did not take him long to change his tune, meet with the committee, and publish an apology for his behavior. In a missive dated four days after the committee’s advertisement, Punderson reiterated the charges against him and “seriously and heartily” declared the he was “sorry I have drank any Tea since the first of March” and “will drink no more until the Use thereof shall generally be approved in North-America.” In addition, he apologized for “all and every Expression that I have at any Time uttered against the Association of the Continental Congress.” Furthermore, Punderson pledged that he “will not at any Time do any Thing that shall be inimical to the Freedom, Liberties, and Privileges of America, and that I will ever be friendly thereto.” He requested that his “Neighbours and fellow-Men to overlook” his transgression and “sincerely ask[ed] the Forgiveness of the Committee for the Disrespect I have treated them with.”

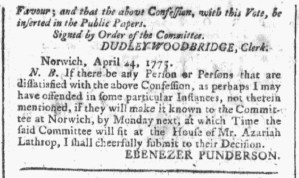

Punderson apparently convinced the committee to give him another chance. Dudley Woodbridge, the clerk, reported that Punderson “appeared before them, and of his own Accord made the above Confession” and seemed “heartily sorry for his … conduct.” In turn, the committee voted to find Punderson’s confession “satisfactory” and recommended that he “be again restored to Favour” in the community. The committee also determined that “the above Confession, with this Vote, be inserted in the Public Papers,” perhaps less concerned with restoring Punderson’s good name than the example his recantation set for other Tories. When the notice appeared in the Norwich Packet, Punderson inserted an additional note that extended an offer to meet with anyone “dissatisfied with the above Confession” and asserted that he would “cheerfully submit” to any further decisions the Committee of Inspection made in response.

Yet what appeared in the Norwich Packet did not tell the whole story. According to Steve Fithian, Punderson “attempted to flee to New York but was captured and returned to Norwich where he spent eight days in jail and only released after signing a confession admitting to his loyalist sympathies.” He did not stay in Norwich long after that. “Several weeks later he fled to Newport, Rhode Island and boarded a ship which took him to England where he remained for the entire Revolutionary War.” Apparently, he convincly feigned the sincerity he expressed, well enough that the committee accepted it. While imprisoned, Punderson wrote a letter to his wife about his ordeal. After arriving in England, he published an account with a subtitle that summarized what he had endured: The Narrative of Mr. Ebenezer Punderson, Merchant; Who Was Drove Away by the Rebels in America from His Family and a Very Considerable Fortune in Norwich, in Connecticut. Just as the Committee of Inspection used print to advance a version of events that privileged the patriot cause, Punderson disseminated his own rendering once he arrived in a place where he could safely do so.

**********

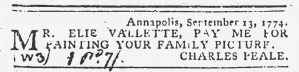

The Committee of Inspection’s notice appeared with the advertisements in the April 20, 1775, edition of the Norwich Packet. Punderson’s confession, however, ran interspersed with news items in the April 27 edition. It may or may not have been a paid notice, but it was certainly an “advertisement” in the eighteenth-century meaning of the word. At the time, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, an advertisement was a “(written) statement calling attention to anything” and “an act of informing or notifying.” Advertisements often delivered local news in early American newspapers. Punderson definitely made news as the imperial crisis became a war.