What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

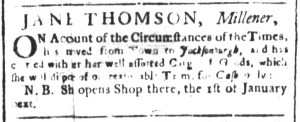

“JANE THOMSON, Millener, ON Account of the Circumstances of the Times, has moved from Town to Jacksonburgh.”

In December 1775, Jane Thomson, a milliner, had been running a shop in Charleston and occasionally placing newspaper advertisements for several years. She likely followed news from Massachusetts about the hostilities that commenced at Lexington and Concord the previous April as well as updates from the meetings of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. She probably knew that residents of urban ports beyond New England felt anxious that the British would target their homes next, prompting some to move to the countryside for better security. She apparently experienced the same anxiety and charted a new course accordingly. In the December 22 edition of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, the only newspaper still being published in the colony at the time, she announced that “ON Account of the Circumstances of the Times” she “has moved from Town [or Charleston] to Jacksonburgh,” nearly fifty miles to the west. Thomson informed readers that she “has carried with her her well assorted [illegible] of Goods, which she will dispose of on reasonable Terms for Cash only.” She planned to open her shop in her new location on January 1, 1776.

Thomson’s notice will be one of the last advertisements from the South-Carolina and American General Gazette featured on the Adverts 250 Project. The newspaper continued publication until the end of February 1781, with some suspensions due to the Revolutionary War, and a complete run through December 1779 has been preserved buy the Charleston Library Society. However, issues for 1776, 1777, 1778, and 1779 have not been digitized for greater accessibility. In producing the Adverts 250 Project and the Slavery Adverts 250 Project, I have relied on the South Carolina Newspapers collection from Accessible Archives (now part of History Commons), yet that coverage ends with the issue for December 22, 1775. Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers has five more issues (September 4, 1776; April 10, 1777; February 19, June 4, and October 1, 1778) that I will incorporate into the project at the appropriate times, but the Adverts 250 Project and the Slavery Adverts 250 Project will not offer the same sustained look at advertising and the intersections of commerce, politics, and everyday life in Charleston during the Revolutionary War as I have attempted to provide for the period of the imperial crisis that ultimately led to that war. The stories of that important urban port have always been truncated according to which advertisements I selected to feature. Now they will be absent altogether.