What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

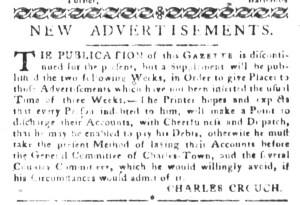

“THE PUBLICATION of this GAZETTE is discontinued for the present.”

It was the last issue of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, though Charles Crouch, the printer, may not have known it at the time. The “NEW ADVERTISEMENTS” in the August 1, 1775, edition began with an announcement that the “PUBLICATION of this GAZETTE is discontinued for the present,” suggesting that the printer might revive it at a later time. For now, he promised that “a Supplement will be published the two following Weeks, in Order to give Places to those Advertisements which have not been inserted the usual Time of three Weeks.” Perhaps Crouch did distribute those supplements, but extant copies have yet to be located. However, a nearly complete run of issues from the newspaper’s founding on December 17, 1765, through its last regular issue nearly a decade later does survive. In 1908, A.S. Salley, Jr., noted, “The Charleston Library Society possesses an almost complete file of Crouch’s paper, only twenty-five numbers being missing from the ten years of the file.”[1] Four decades later, Clarence Brigham did not record any missing issues in the Charleston Library Society’s collections in his History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820.[2] Perhaps in the intervening years the Charleston Library Society acquired copies of those missing issues.

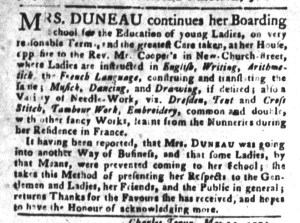

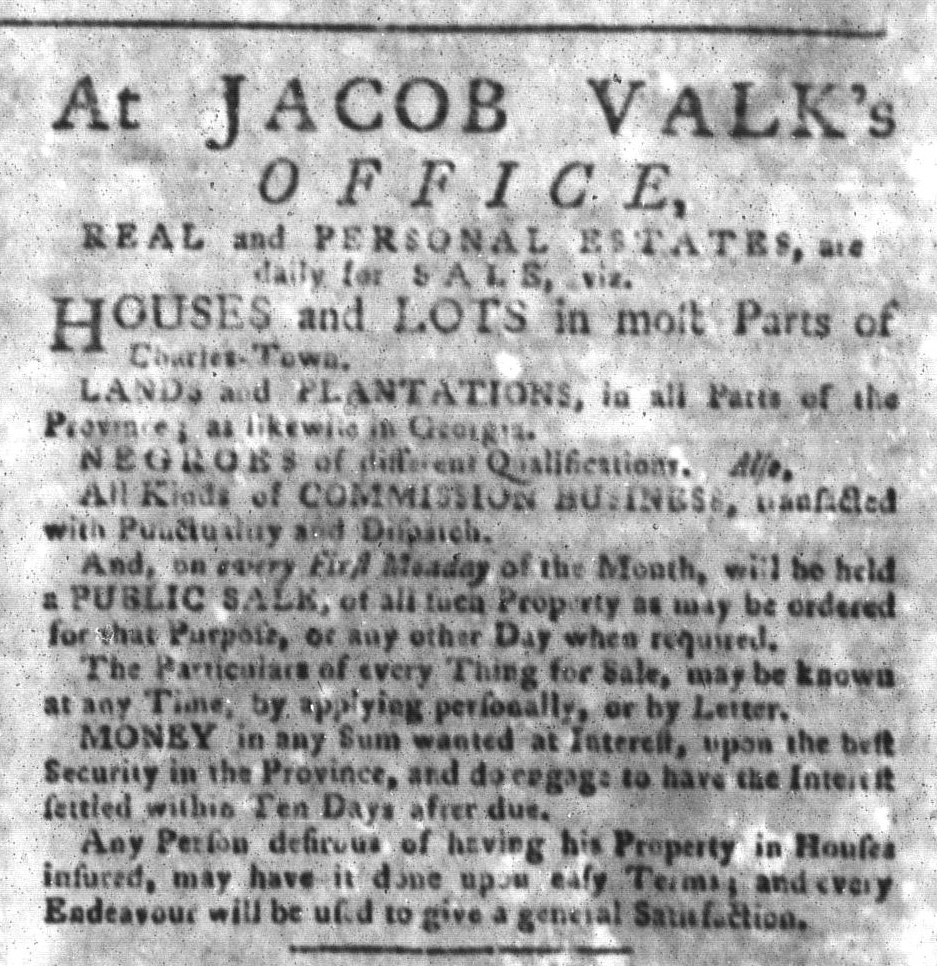

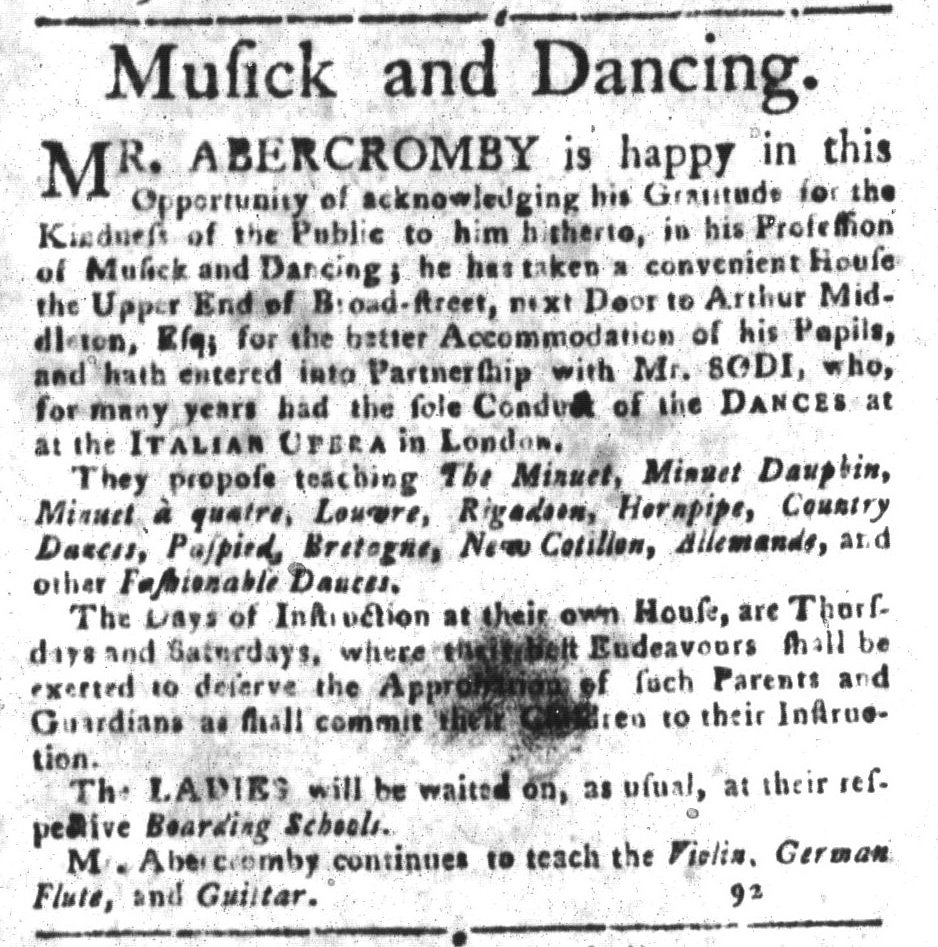

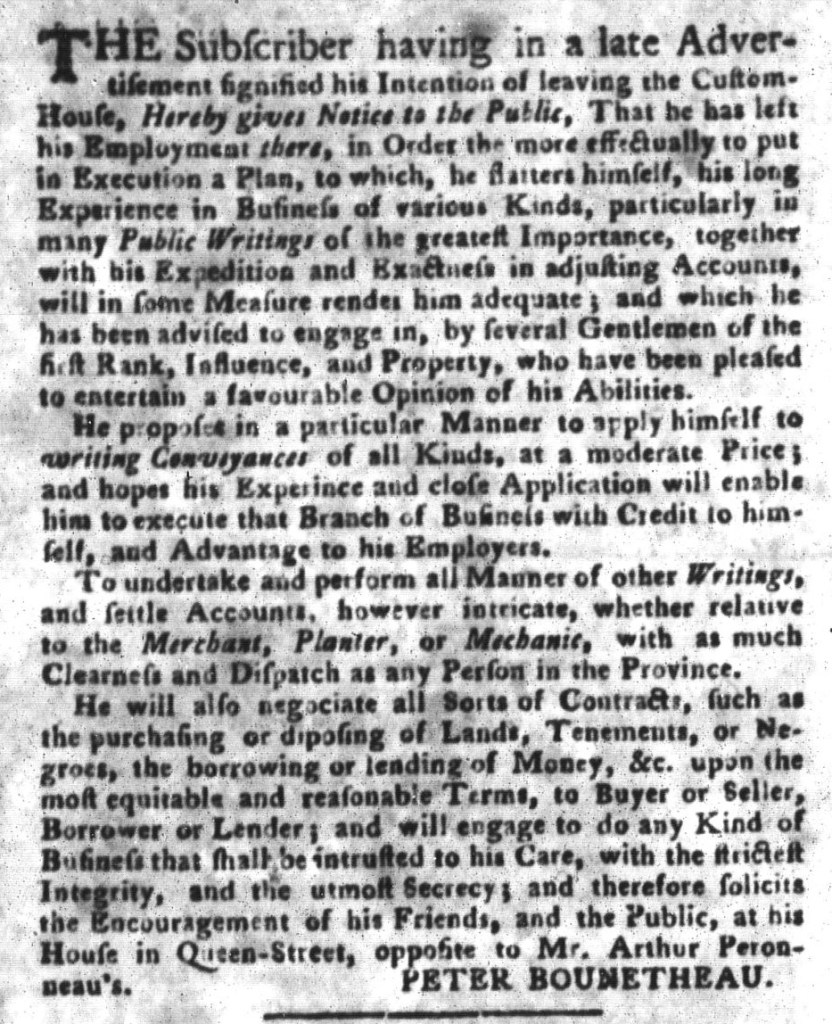

Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy who later penned The History of Printing in America in 1810, wrote a short history of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. The newspaper, he explained, “was established in opposition to the British American stamp act … and was published without stamps.” That garnered acclaim from the public, earning Crouch a reputation as a “sound whig” or patriot. “The general opposition of the colonies to the stamp act induced the public to patronize this Gazette. It immediately gained a large list of respectable subscribers, and a full proportion of advertising customers.” Crouch did not leave that to chance. He included “Gazette” in the title, like the printers of the South-Carolina Gazette and the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, “in order to secure certain advertisements, directed by law to be ‘inserted in the South Carolina Gazette.’” In addition to those notices, Crouch’s newspaper also carried a variety of advertisements for consumer goods and services as well as notice presenting enslaved people for sale or offering rewards for the capture and return of enslaved people who liberated themselves by running away from their enslaver. Each sort of advertisement represented a lucrative revenue stream for the printer. Among its competitors in Charleston, Thomas asserted, Crouch’s newspaper was the only one that “appeared regularly.”[3] Others sometimes had gaps in publication.

Even though Crouch hoped to resume publishing the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, he did not have the opportunity. In late August 1775, he boarded a vessel headed to Philadelphia. He sought supplies for his printing office, especially paper that had grown scarce. The ship was lost at sea. Thomas stated that Crouch’s widow published the newspaper for a short time, but Salley clarifies that Ann Crouch “revived her husband’s paper under the name of The Charlestown Gazette” in 1778 and “conducted it until the capture of Charles Town by the British in 1780.”[4] A few issues have survived and been digitized for greater access by scholars and the public. The Adverts 250 Project will examine those at the appropriate time. For now, the demise of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journalcertainly had ramifications in Charleston and beyond. In August 1775, readers in South Carolina had one less source of news and one less publication for disseminating advertisements.

**********

[1] A.S. Salley, Jr., “The First Presses of South Carolina,” Proceedings and Papers (Bibliographical Society of America) 2 (1907-1908): 66.

[2] Clarence Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820 (Worcester, Massachusetts: American Antiquarian Society, 1947), 1039.

[3] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 571, 582.

[4] Salley, “First Presses of South Carolina,” 65-66.