What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

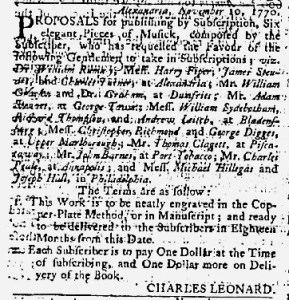

“PROPOSALS For PRINTING by SUBSCRIPTION.”

In the summer of 1771, James Humphreys wished to publish an American edition of William Robertson’s History of Scotland during the Reigns of Queen Mary and of King James VI, perhaps inspired in part by Robert Bell’s efforts to publish an American edition of Robertson’s History of the Reign of Charles the Fifth, Emperor of Germany. To that end, Humphreys adopted a method pursued by Bell and other printers and publishers when they wished to gauge interest and incite demand for a publication. He distributed a subscription notice, calling on subscribers to reserve copies in advance. The number of subscribers determined the viability of a publication.

Such endeavors depended on regional, rather than local, markets. Humphreys promoted the project in his own city, Philadelphia, but he also placed “PROPOSALS For PRINTING by SUBSCRIPTION” in newspapers published elsewhere, including in the July 15, 1771, edition of the Boston-Gazette. He listed the printers of that newspaper, Benjamin Edes and John Gill, as local agents who accepted subscriptions, but also noted that “the different Printers and Stationers on the continent” handled subscriptions in other places. Such projects often depended on cultivating networks of local agents.

In the “CONDITIONS,” Humphreys specified that the two volumes of Robertson’s History would go to press “as soon as three hundred subscribers have given their names.” To entice prospective buyers, he pledged that the “names of the subscribers [would] be printed in the beginning of the first volume.” As a result, subscribers received more than just the books; they also received recognition as members of a learned community who simultaneously supported American publications as alternatives to imported books. Humphreys charged one dollar per volume, two dollars total, as well as the “expense of sending them to distant places.” Unlike some other subscription projects, however, he did not collect money in advance to secure the commitments made by subscribers and offset initial costs for producing the books. Instead, he declared, “No money is expected but on delivery of the books.” He likely hoped to attract more subscribers by not requiring a down payment.

Unfortunately for Humphreys, his marketing efforts apparently did not yield the necessary number of subscribers to move forward with the project. He acknowledged Bell’s “lately published beautiful History of CHARLES V. Emperor of Germany” in the subscription notice. Rather than creating an opening for another printer to publish an American edition of one of Robertson’s other works, Bell and his aggressive marketing campaign in newspapers throughout the colonies may have saturated the market.