What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

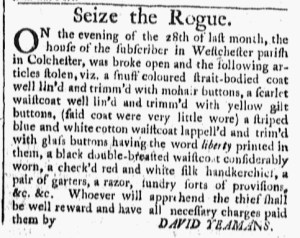

“SEIZE the ROGUE!”

Most articles in eighteenth-century newspapers did not have headlines. Considering that most issues consisted of only four pages and most newspapers were published just once a week, printers did not have the space to include short summaries of the content. They expected subscribers and others would engage in practices of intensive reading, working their way through the articles, letters, and other “intelligence” that appeared in their newspapers. Some regular features did have headlines, such as “THOMAS ALLEN’s Marine List” and the “POET’S CORNER” in the Connecticut Gazette, but most articles did not.

Advertisers, on the other hand, sometimes devised headlines for the notices they paid to insert in early American newspapers. Quite often their names served as the headline. Such as the case for an advertisement placed by Nathan Bushnell, Jr., in the June 9, 1775, edition of the Connecticut Gazette. He ran the same advertisement in the New-England Chronicle, deploying the name of the service he provided, “CONSTITUTIONAL POST,” as a secondary headline. Elsewhere in the Connecticut Gazette, an advertisement intended to raise funds for “Building a Meeting-House, for Public Worship” in Stonington deployed a headline to inform readers that it contained the “Scheme of a LOTTERY” that listed the number of tickets and the available prizes.

John Holbrook of Pomfret intended to attract attention with the headline for his advertisement: “SEIZE the ROGUE!” Holbrook explained that a “noted thief” had stolen various items from his house during the night of April 28, 1775. He described “a large silver WATCH with a silver-twist chain, a clarat colour’d coat lately let out at the sides and at the outsides of the sleeves, a jacket near the same colour, both of them lined, … [and] a psalm book with the names of Asa Sharper and Caleb Sharpe in it,” along with other pilfered items. Holbrook offered a reward to “Whoever brings said villain … with the above articles” or a smaller reward for just “the said thief without the articles.” Given the amount of time that had passed, there was a good chance that the thief had fenced or sold the stolen items, giving some colonizers greater access to consumer culture through what Serena Zabin has termed an informal economy. Whatever the fate of the watch, coat, and psalm book, Holbrook used a lively headline to increase the chances that readers would take note of his advertisement. He did so at a time that editors and others employed in printing offices did not yet craft headlines for most of the news they published.