What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

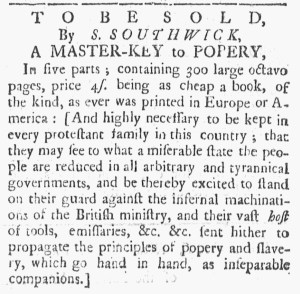

“A MASTER-KEY to POPERY … highly necessary to be kept in every protestant family.”

As the imperial crisis intensified in the summer of 1774, Solomon Southwick, printer of the Newport Mercury, peddled an American edition of A Master-Key to Popery. For many months, Southwick circulated subscription proposals in his own newspaper and several others in New England, seeking to generate sufficient interest to make publishing the book a viable venture. He took it to press in 1773 and distributed to subscribers the copies they had reserved. Apparently, he produced surplus copies that he offered for sale at his printing office, perhaps anticipating opportunities to disseminate the assertions made by Antonio Gavin, formerly a “secular Priest in the Church of Rome, and since 1715, Minister of the Church of England.” Who better than a priest who converted to Protestantism to reveal the true workings of the Catholic Church?

Southwick addressed the subscription proposal to “all Protestants of every Denomination, throughout America, and all other Friends to religious and civil LIBERTY.” He considered an American edition necessary because “POPERY has lately been greatly encouraged, by the higher Powers in Great-Britain, in some Parts of America, and the West-Indies” and “if successful must prove fatal and destructive to every Liberty, Civil and Religious, which is dear to a rational Being.” To guard against that, Southwick offered the book as a “more full Account of the wicked and abominable Practices of the Romish Priests, than any Piece ever printed in this Country.” He echoed those sentiments when he advertised the book once again in the summer of 1774. He promoted it as “highly necessary to be kept in every protestant family in this country; that they may see to what a miserable state the people are reduced in all arbitrary and tyrannical governments.” In turn, they would “stand on their guard against the infernal machinations of the British ministry, and their vast host of tools, emissaries, &c. &c. sent hither to propagate the principles of popery and slavery, which go hand in hand, as inseparable companions.” Puritans in New England and their descendants had long reviled Catholicism. Within living memory, they had fought against (and defeated) Catholics in New France during the Seven Years War, often suspicious that Catholic agents had infiltrated their colonies. In publishing and marketing A Master-Key to Popery, Southwick fanned the flames of anti-Catholic sentiment.

His new effort to sell the book occurred as Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in response to the Boston Tea Party. When his advertisement appeared in the July 25, 1774, edition of the Newport Mercury, Boston’s harbor had already been closed and blockaded for nearly two months since the Boston Port Act went into effect and the colonies were learning of other legislation. The text of the Massachusetts Government Act filled the first two pages of that issue. In addition, colonial newspapers had recently published reports that Parliament considered the Quebec Act. Colonizers anticipated that it would pass; indeed, a few weeks later they received word that the king had given royal assent to both the Quebec Act and the Quartering Act. Among its various provisions, the Quebec Act allowed for residents to practice Catholicism freely and allowed the Catholic Church to impose tithes. It also granted land in the Ohio Country to the province of Quebec, frustrating British colonizers who intended to settle there or earn fortunes as land speculators. Crown and Parliament seemed to favor Catholic enemies that colonizers in New England had helped to fight and defeat.

Southwick seemingly saw publishing A Master-Key to Popery as part of the information campaign that he waged against British authorities and their allies, “tools,” and “emissaries.” Readers had their own responsibility to engage with what he published, both in the book and in his newspaper. Among the local news in the July 25 edition of the Newport Mercury, Southwick reported that in the previous week he “received a considerable number of new subscribers” who “have stepped forth, at this time, not merely as friends to him, but as friends and supporters of the just and absolute rights of the colonies.” For Southwick and many other colonizers, anti-Catholicism played a role in interpreting the political landscape and expressing their patriotism.