What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

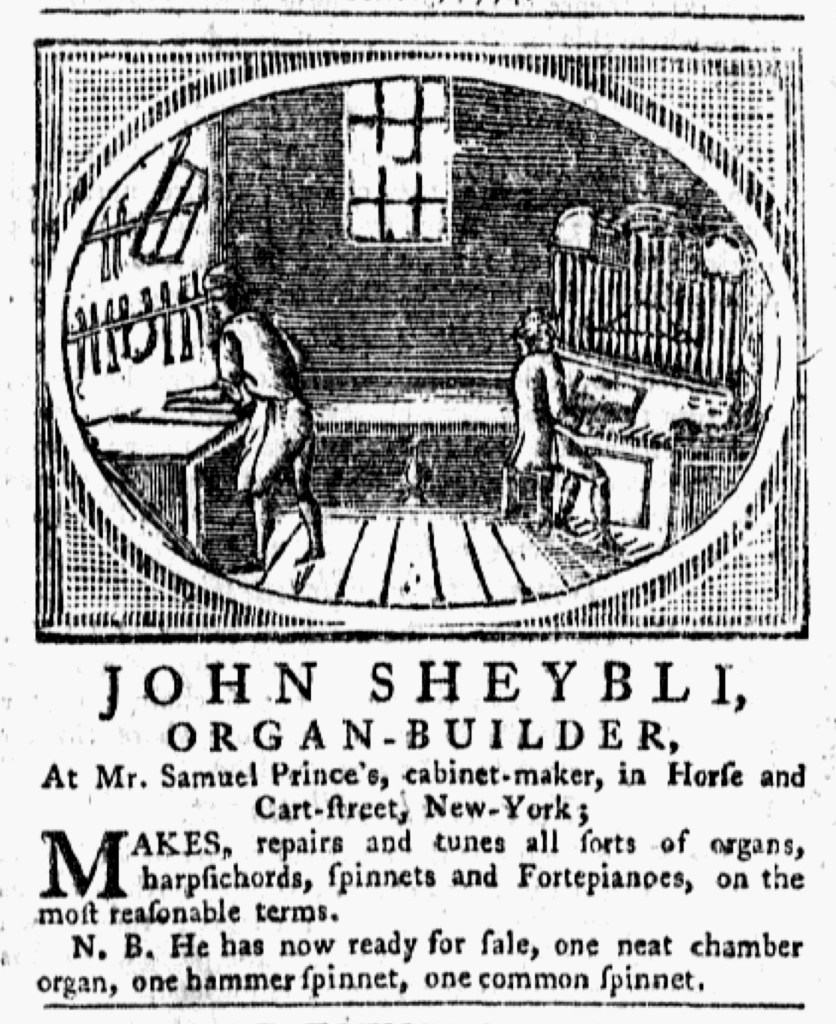

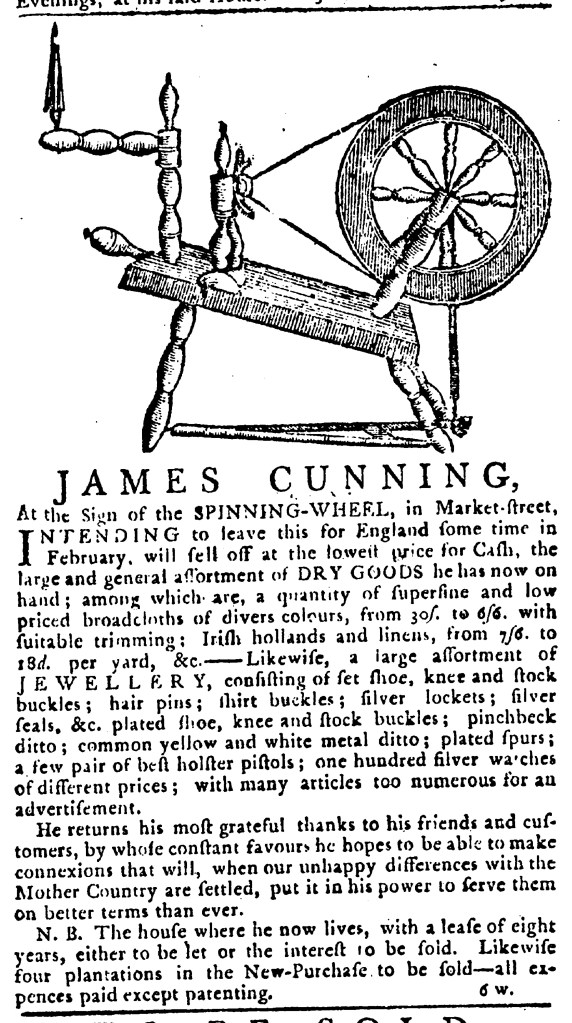

“The Sign of the SPINNING-WHEEL.”

James Cunning ran a shop “At the Sign of the SPINNING-WHEEL” in Philadelphia in the early 1770s, occasionally advertising in the local newspapers. In the fall of 1774, he made plans to depart for England the following February. His preparations included running a new notice and selling his remaining merchandise “at the lowest price for Cash.” He did not indicate why he planned to leave Philadelphia or how long he would be away, but he did state that during his time on the other side of the Atlantic that he “hopes to be able to make connexions that will, when our unhappy differences with the Mother Country are settled, put it in his power to serve [his customers] on better terms than ever.” Neither Cunning nor readers knew that armed conflict between the colonies and Britain would erupt in Massachusetts in April 1775 or that the “unhappy differences” would be settled with a war for independence that would last eight years.

They did know, however, that the imperial crisis had intensified to the point that delegates from twelve colonies convened the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in September and October 1774. They also knew that meeting resulted in the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement intended to unify the colonies. That pact was scheduled to go into effect on December 1, the day after Cunning’s advertisement made its first appearance in the Pennsylvania Journal. Envisioning the difficulty ahead, the shopkeeper may have decided to make the best of the situation by liquidating his inventory and making plans for what he hoped would be a better future.

Given the stakes, Cunning sought to increase the chances that readers would take note of his advertisement. To that end, he included a woodcut that depicted a spinning wheel, the same device that marked the location of his shop. He had incorporated that image into advertisements he placed in October 1771 and December 1772. More recently, including in an advertisement in the December 6, 1773, edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, he did not feature a visual image. When he decided to visit England, Cunning either remembered where he had stored the woodcut or managed to find it after some searching, determined to use it to his advantage during difficult times. A nick in the spindle reveals that it was the same woodcut from his earlier advertisements, collected from the printing office where John Dunlap published the Pennsylvania Packet and later delivered to the printing office where William Bradford and Thomas Bradford published the Pennsylvania Journal. The shopkeeper intended, at least one more time, to get a return on the investment he made when he commissioned the woodcut.