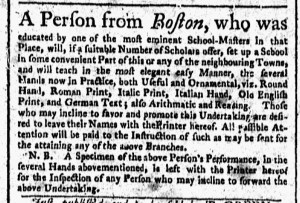

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A Person from Boston … will teach … the several Hands now in Practice.”

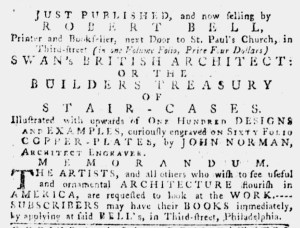

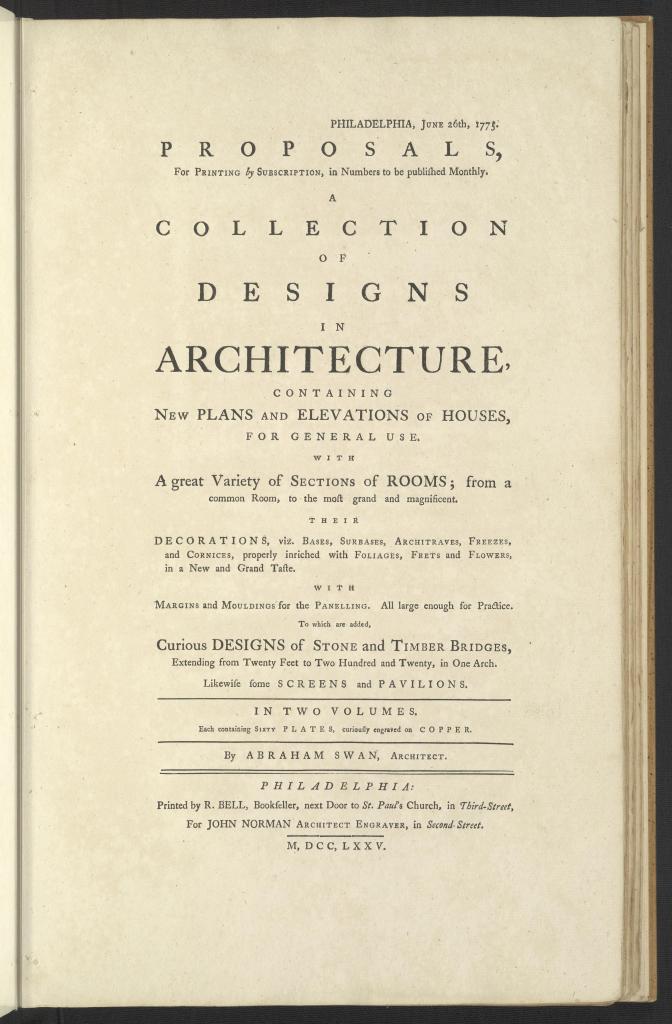

A “Person from Boston” sought to open a school in southwestern Connecticut in the summer of 1775. He placed an advertisement in the Connecticut Gazette in hopes of reaching prospective pupils and their families, stating that he would commence instruction in New Haven “or any of the neighbouring Towns” if a sufficient number of “Scholars” signed up for lessons. In addition to reading and arithmetic, he taught “the several Hands now in Practice, both Useful and Ornamental,” including “Round Hand, Roman Print, Italic Print, Italian Hand, Old English Print, and German Text.”

The schoolmaster did not give his name, instead merely identifying himself as a “Person from Boston, who was educated by one of the most eminent School-Masters in that Place.” He asked that those “who may incline to favor and promote this Undertaking … leave their Names with the Printer” of the Connecticut Gazette. Timothy Green, the printer, likely did more than keep a list of names of interested students. He served as a surrogate for the anonymous schoolmaster. Even though residents of New Haven and the vicinity did not know the “Person from Boston,” they did know Green and could ask him for his impressions of the man, whether he seemed reputable and capable of the instruction he proposed. Furthermore, the unnamed schoolmaster left “A Specimen of the above Person’s Performance, in the several Hands mentioned” at the printing office “for the Inspection of any Person who may incline the forward the Undertaking.” Anyone who visited the printing office for that purpose could chat with Green about the “Person from Boston” as they examined the “Specimen.”

They might have learned that he was a refugee from Boston who left the city following the battles at Lexington and Concord. When the siege of Boston commenced, Governor Thomas Gage and the Massachusetts Provincial Congress negotiated an agreement that allowed Loyalists to enter the city and Patriots and others to depart. Other refugees from Boston resorted to newspapers advertisements to attract customers and clients after taking up residence in new towns. It may have been a similar situation for the “Person from Boston” who found himself in New Haven at the beginning of the Revolutionary War.