What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

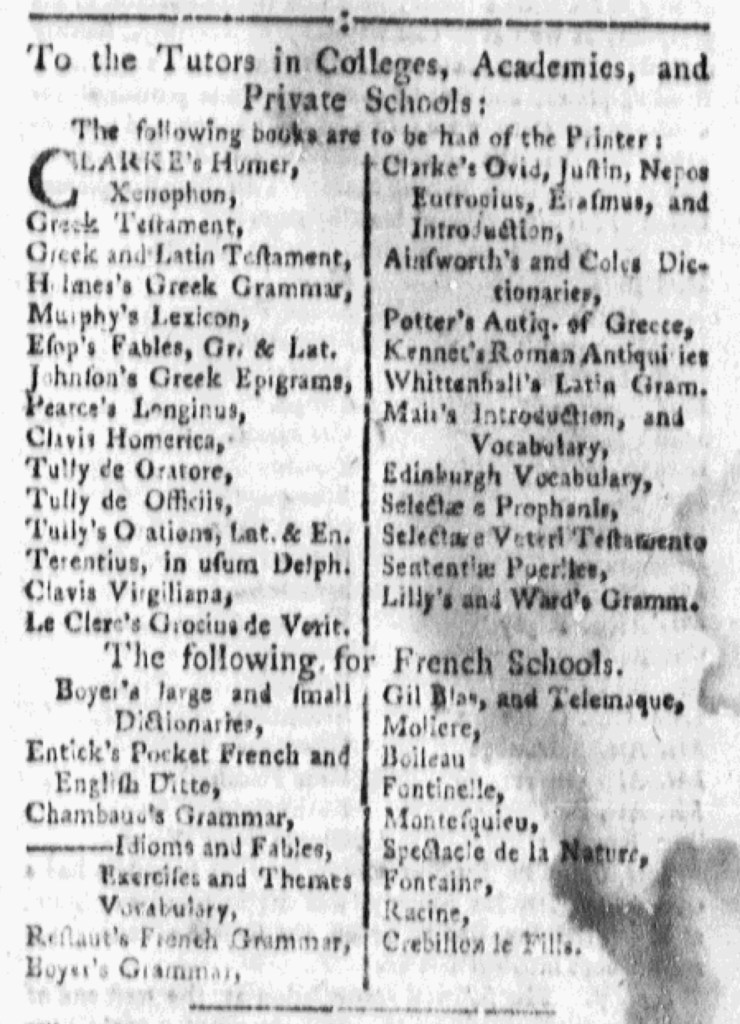

“To the Tutors in Colleges, Academies, and Private Schools.”

James Rivington, the printer of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, sold books as an additional revenue stream rather than relying solely on subscriptions and advertisements. Such was the case with other printers throughout the colonies, their printing offices doubling as bookstores. Rivington’s newspaper often carried advertisements for books, pamphlets, and almanacs that he stocked. He printed some of them, acquired others from other colonial printers, and imported most of them from England. Some advertisements featured a single title. The November 16, 1775, edition, for instance, featured an advertisement for “A DICTIONARY OF THE Holy Bible” that included the prints, size, and number of volumes along with a description of the contents. Other advertisements listed multiple titles without providing additional information.

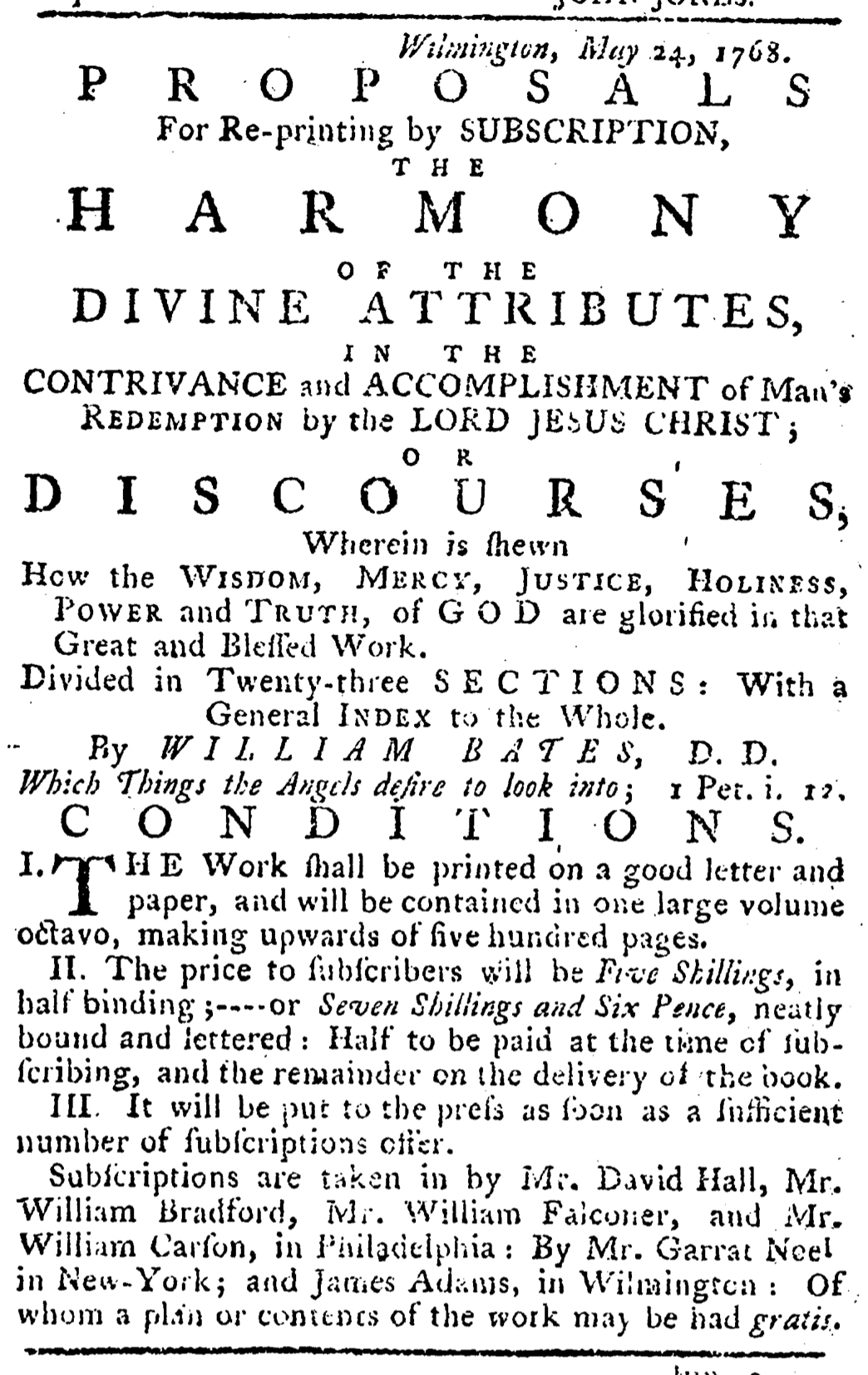

On occasion, Rivington ran advertisements that promoted books and pamphlets with a common theme. With a headline proclaiming, “The American Controversy,” an advertisement published in February 1775 listed ten pamphlets “published on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.” He deployed the same strategy in another notice that ran on November 16, this time addressing “the Tutors in Colleges, Academies, and Private Schools.” He then gave the titles of more than two dozen books he considered suitable for classrooms, such as “CLARKE’s Homer,” “Greek and Latin Testament,” “Esop’s Fable, Gr[eek] & Lat[in],” “Tully’s Orations, Lat[in] & En[glish],” “Ainsworth’s and Coles Dictionaries,” “Whittenhall’s Latin Gram[mar],” and “Lilly’s and Wards Gramm[ar].” Rivington implied that those books should have been familiar to tutors. In addition to those titles, he devoted the final third of the advertisement to books “for French Schools,” including “Boyer’s large and small Dictionaries,” “Entick’s Pocket French and English [Dictionary],” “Chambaud’s Grammar,” “[Chambaud’s] Exercises and Themes,” “Moliere,” and “Montesquieu.” While Rivington usually marketed most books and pamphlets to general audiences and prospective customers of all backgrounds, especially when his advertisements consisted of catalogs of books available at his printing office, he occasionally attempted to boost sales by directing particular kinds of readers to carefully curated lists of titles. In this case, tutors and schoolmasters did not need to pore over lengthy lists of books and pamphlets not relevant or not appropriate to their lessons when Rivington presented a specialized catalog for their convenience.