What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

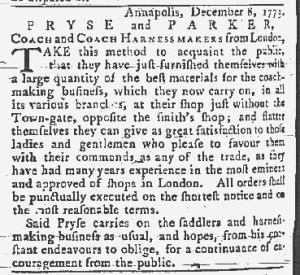

“They have had many years experience in the most eminent and approved of shops in London.”

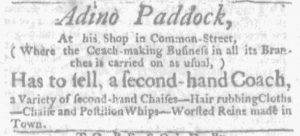

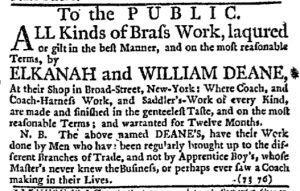

The partnership of Pryse and Parker constructed coaches and other sorts of carriages as well as harnesses at their shop in Annapolis. In December 1773, they placed an advertisement in the Maryland Gazette to inform prospective customers that they “just furnished themselves with a large quantity of the best materials for the coach-making business.” They introduced themselves as “from London,” though that did not necessarily mean that they were recent arrivals in Annapolis. After all, some artisans continued to burnish their London credentials for years after they set up shop in colonies. Pryse and Parker’s advertisement did not indicate how long they had pursued their trade in town, though a brief note at the end advised that Pryse “carries on the saddlers and harness-making business as usual, and hopes … for a continuance of encouragement from the public.” That suggested that Pryse had been in Annapolis long enough to gain some familiarity, even if the partnership with Parker was relatively new. Just over a year earlier, Pryse did indeed advertise on his own.

No matter how long they had been making carriages in Annapolis, Pryse and Parker considered it helpful to their marketing efforts to tout their connections to the most cosmopolitan city in the empire. In addition to identifying themselves as “from London,” they trumpeted that “they have had many years experience in the most eminent and approved of shops in London.” Although they stated that they “flatter themselves they can give as great satisfaction to those ladies and gentlemen who please to favour them with their commands, as any of the trade,” Pryse and Parker thought that the time they labored in those “most eminent and approved of shops in London” should distinguish them from their competitors. They expected that the local gentry who could afford to purchase and maintain coaches and carriages would place a premium on acquiring those items from artisans with the kind of background they boasted. Even as colonizers protested against the Tea Act and other measures enacted by Parliament, many of them continued to consider links to London a selling point when engaging the services of artisans.