What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“An unwearied Pedlar of that baneful herb TEA.”

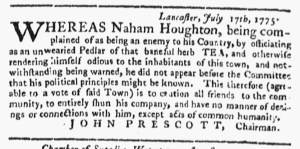

Naham Houghton of Lancaster, Massachusetts, went too far and there had to be consequences. An advertisement in the August 16, 1775, edition of the Massachusetts Spy gave an abbreviated account of what occurred. According to John Prescott, chairman of the local Committee of Inspection, there had been complaints that Houghton behaved as “enemy to his Country, by officiating as an unwearied Pedlar of that baneful herb TEA, and otherwise rendering himself odious to the inhabitants of this town.” Prescott did not elaborate on the other infractions. Selling tea was enough to get Houghton into hot water.

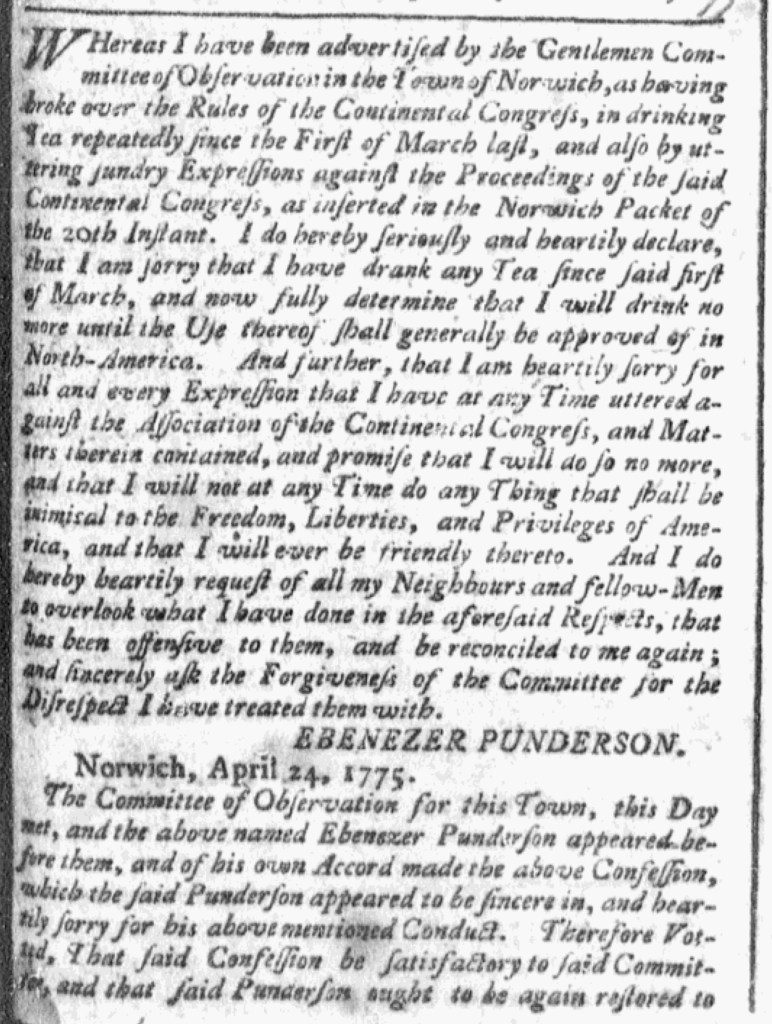

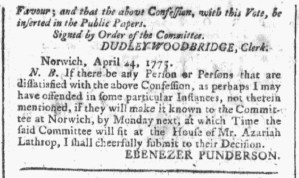

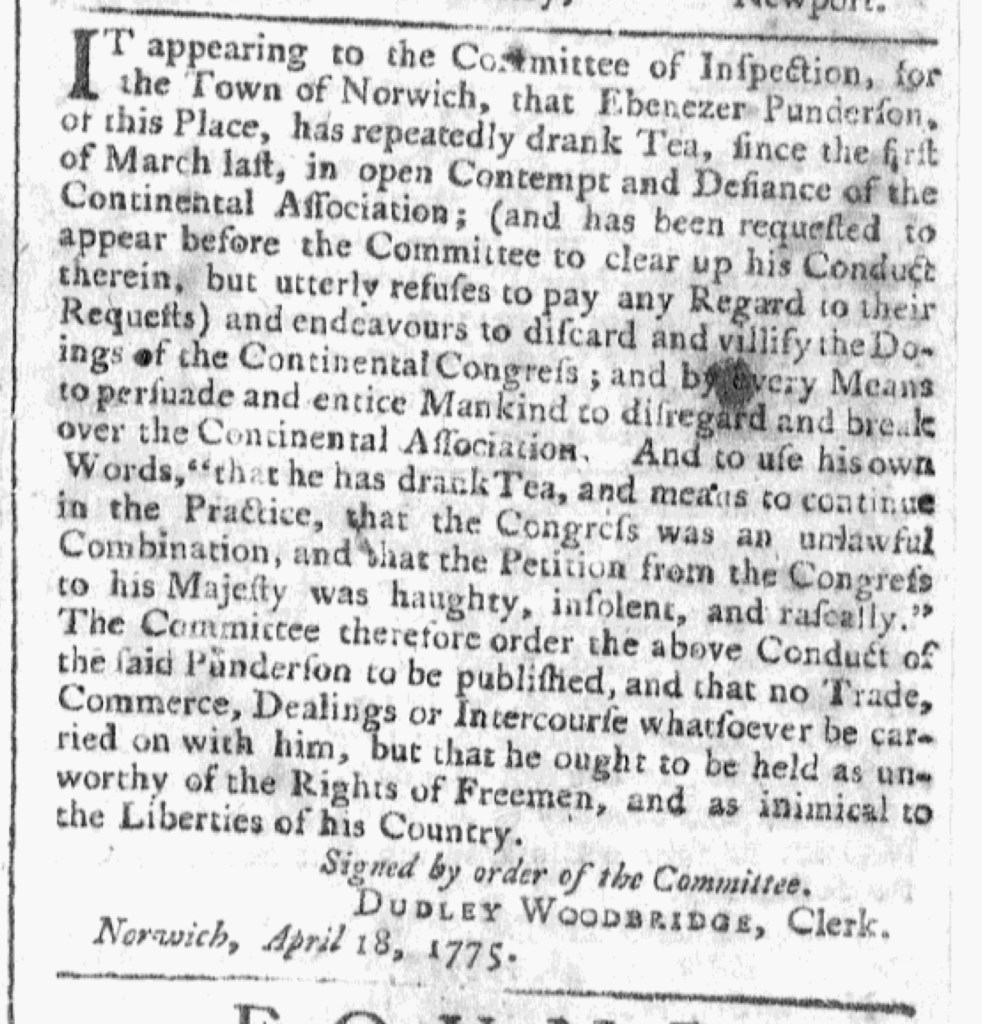

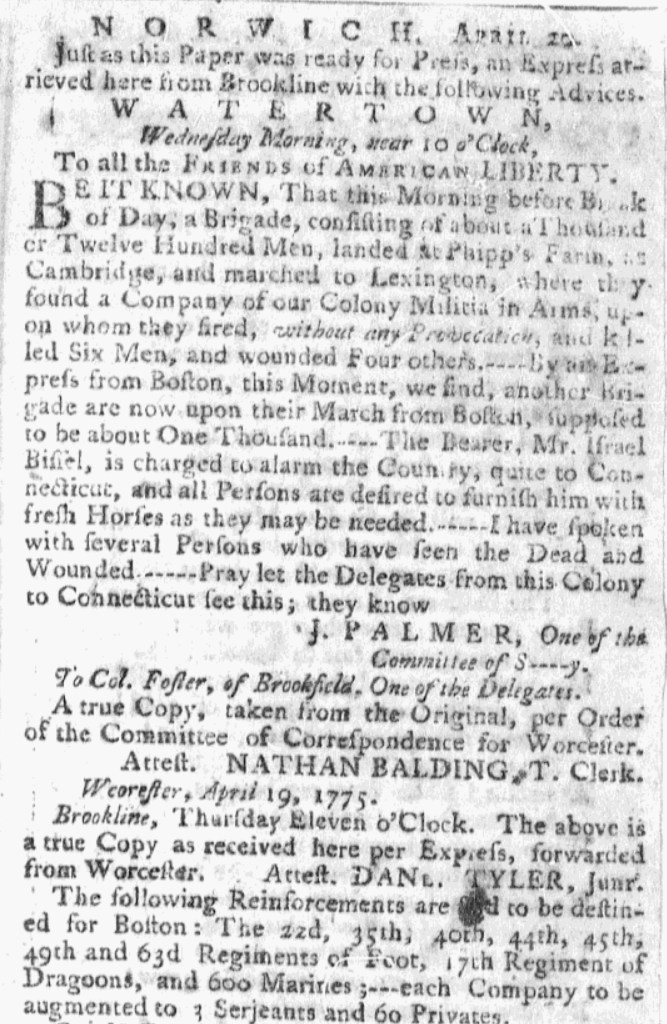

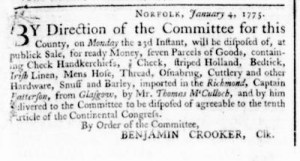

That violated the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement devised by the First Continental Congress in response to the Coercive Acts imposed by Parliament in retribution for the Boston Tea Party. The eleventh article outlined an enforcement mechanism, stating that a “Committee be chosen in every County, City, and Town” to monitor compliance with the pact. When a majority determined that someone committed a violation, they would “cause the truth of the case to be published in the Gazette, to the End that all such foes to the rights of British America may be publickly known and universally condemned as Enemies.” In turn, the rest of the community would “break off all Dealings with him, or her.”

The committee in Lancaster apparently sought to work with Houghton in seeking an explanation for his actions, but to no avail. Prescott reported that Houghton refused to “appear before the Committee that his political principles might be known” even though he had been warned. Neither the committee nor the town tolerated such defiance. The town voted “to caution all friends to the community, to entirely shun his company,” as the Continental Association instructed, “and have no manner of dealings or connections with him, except acts of common humanity.” Selling tea continued to resonate as a political act, yet it was only one of many offenses that made Houghton “odious” to his neighbors. At the same time that others suspected of Tory sympathies confessed their errors and used newspaper advertisements to rehabilitate their reputations, Houghton steadfastly refused to bow to such pressure exerted by the Committee of Inspection. He instead became the subject of an advertisement that made clear, far and wide, that he was not in good standing in his community.