What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

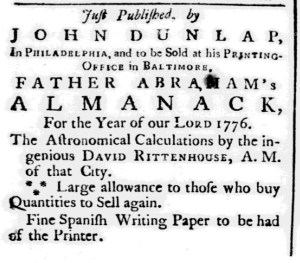

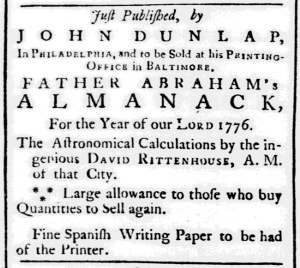

“FATHER ABRAHAM’s ALMANACK, For the Year of our LORD 1776.”

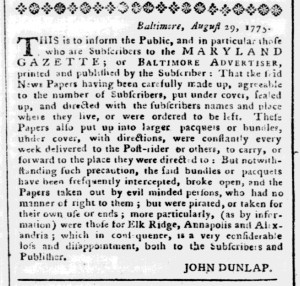

John Dunlap, the printer of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, apparently had surplus copies of “FATHER ABRAHAM’s ALMANACK, For the Year of our LORD 1776,” that he hoped to sell in the middle of February of that year. Although the “Astronomical Calculations by the ingenious DAVID RITTENHOUSE” for the first six weeks of the year were no longer of use to readers, the rest of the contents still had value. Hoping to move some or all the remaining copies out of his printing office in Baltimore, Dunlap once again placed an advertisement that had first appeared in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette in October, well before the new year began and readers would refer to the calendars and astronomical calculations in the handy reference manual. Prospective customers knew that the phrase “Just Published” at the beginning of the advertisement merely meant that copies were available to purchase, not that the almanacs just came off the press.

In addition to operating a printing shop and publishing a newspaper in Baltimore, Dunlap also ran a printing shop in Philadelphia. It was there, according to his advertisement, that he had printed the almanac and then sent copies to his printing office in Baltimore. He had also advertised the almanac in the newspaper he published in Philadelphia, Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. He did not, however, continue running advertisements for the almanac in that newspaper in February 1776. Perhaps he sold out of copies in Philadelphia. After all, he established his printing office and newspaper there before his second printing office and newspaper in Baltimore. Consumers in Philadelphia and its hinterlands had greater familiarity with Dunlap, the printer, and Rittenhouse, the astronomer and mathematician who did the calculations for the almanac. Alternately, Dunlap may not have continued advertising the almanac in the newspaper published at his printing office in Philadelphia because that location received a heavier volume of advertisements. The printer may have determined that the revenue generated from advertisements submitted by customers outweighed any potential revenue from advertising the almanac once again. With limited amount of space in each issue, delivering news also took precedence over yet another advertisement for the almanac. Dunlap and those who labored in his printing offices may have had other reasons for continuing to advertise the almanac in Baltimore but not in Philadelphia. Whatever the explanation, the advertisement in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette became a familiar sight to readers over the course of several months.