What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“AN ORATION … to commemorate the bloody Tragedy of March 5th 1770.”

In the spring of 1771, patriots marked the first anniversary of the “BLOODY TRAGEDY” now known as the Boston Massacre with “AN ORATION Delivered … at the Request of the Inhabitants of the Town of Boston … By JAMES LOVELL.” That started an annual tradition, with Joseph Warren giving the oration in 1772, Benjamin Church in 1773, and John Hancock in 1774. Gathering for the oration became an annual ritual. So did publishing and marketing it.

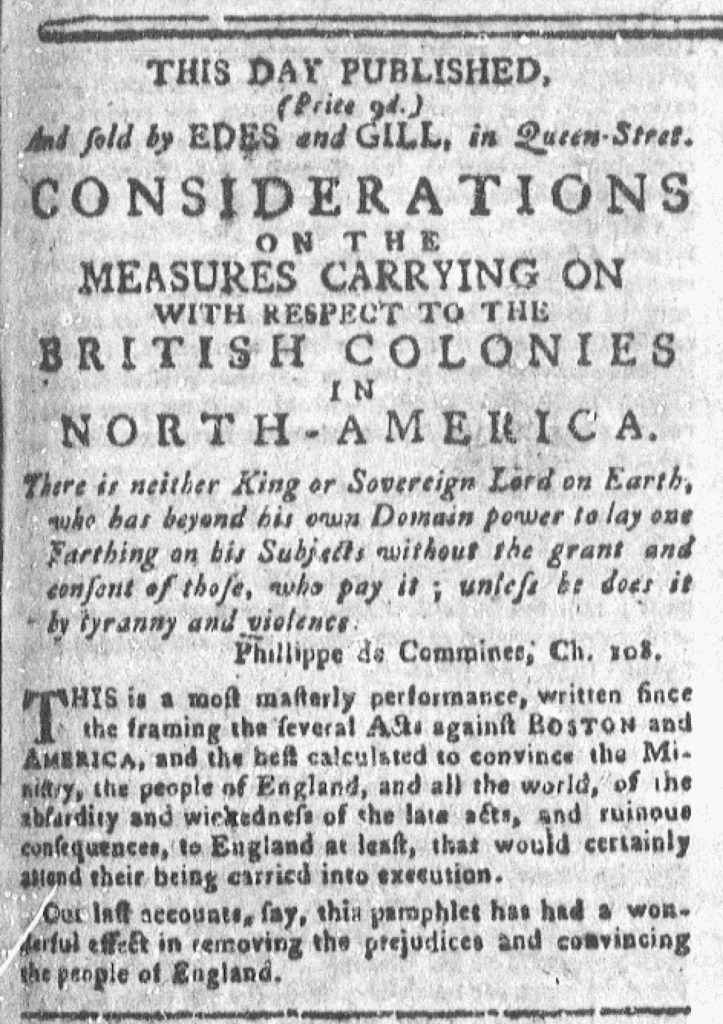

For the fifth anniversary, the “ORATION … to commemorate the bloody Tragedy of March 5th 1770” was once again “delivered by JOSEPH WARREN.” Less than two weeks later, advertisements in the March 17 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter informed readers where they could acquire copies. One indicated that Benjamin Edes and John Gill, the printers of the Boston-Gazette, sold the oration, implying that they also published it. According to the imprint, Edes and Gill printed the address in partnership with Joseph Greenleaf, the proprietor of the Royal American Magazine.

Another advertisement gave readers another option: “In the MASSACHUSETTS SPY, of this Day is published, the WHOLE of the ORATION, delivered by JOSEPH WARREN, Esq; on March 6th , 1775, to commemorate the bloody Tragedy of March 5th, 1770.” Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy, did indeed devote three of the four columns of the third page of his newspaper to Warren’s oration. In an introduction, he reported that it was “this day published, in a pamphlet” and available for sale in addition to appearing in the newspaper. The printer offered multiple ways for readers to engage with the oration. He (and Edes and Gill and Greenleaf) also offered consumers an opportunity to purchase a commemorative item. Readers who previously purchased the orations by Lovell, Warren, Church, and Hancock on previous anniversaries may have been motivated to add to their collections.

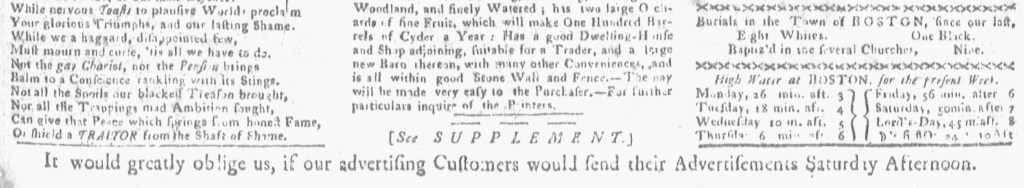

The printer of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter gave the advertisements a privileged place, likely intended to increase the chances that readers took note of them. They appeared one after the other immediately after the weekly account of local marriages and deaths. That meant that the advertisements served as a transition between news items and paid notices. Readers who perused the news yet merely glanced through the advertisements may have been more likely to take note of these first notices as they realized that the remainder of the page featured advertising. A manicule also helped call attention to them, signaling their importance in a town experiencing the distresses of the Boston Port Act and the other Coercive Acts.