What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“SOAP and CANDLES as usual.”

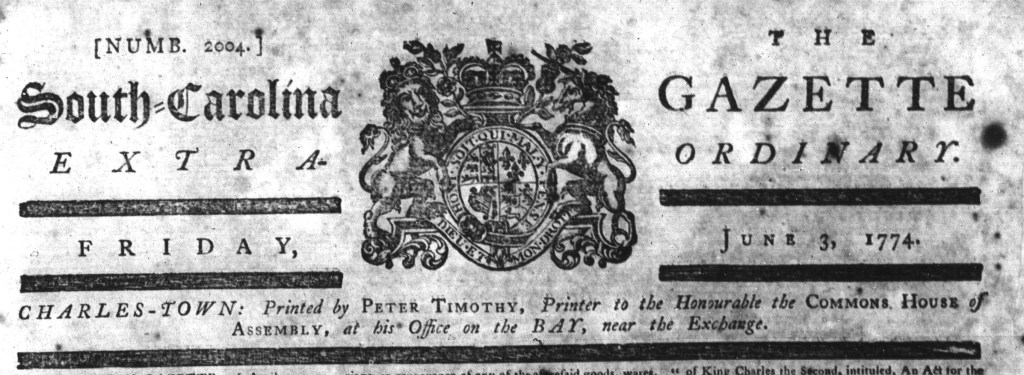

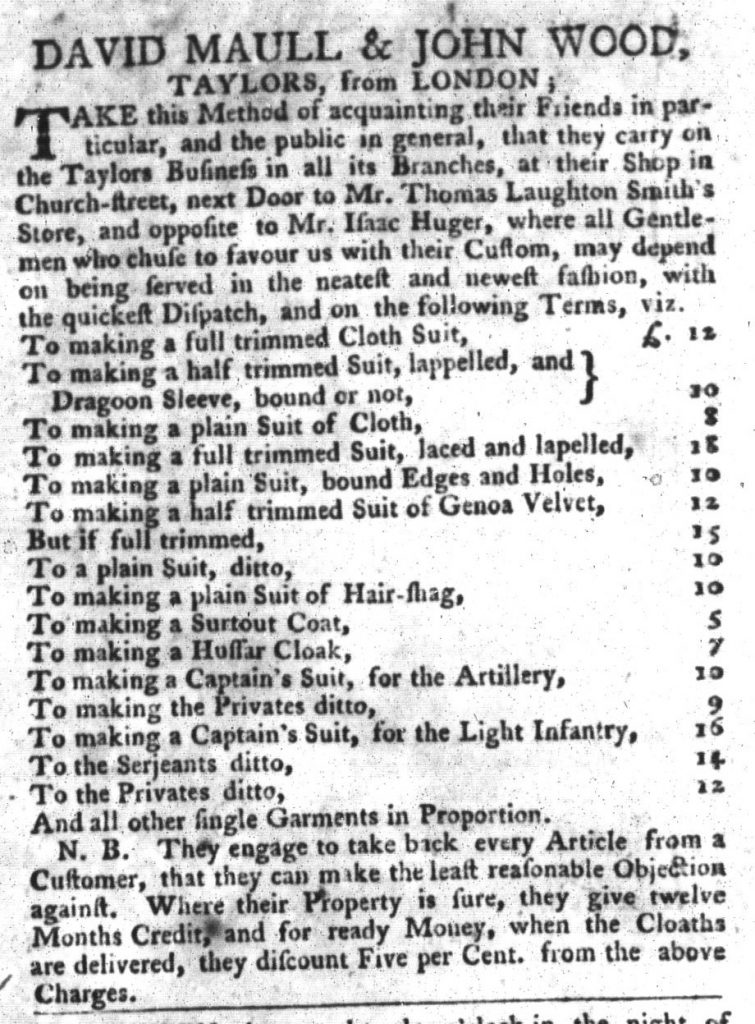

It was an exceptionally rare Sunday edition that carried John Benfield’s advertisement for “RUM of all Sorts” and “SOAP and CANDLES as usual,” Ann Durffey’s advertisement offering an enslaved man for sale, and a handful of other advertisements. Charles Crouch usually published the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal on Tuesdays, but news of recent events merited a broadside extraordinary edition on Sunday, July 9.

Throughout the colonies, printers produced issues of their weekly newspapers on every day from Monday through Saturday, many of them choosing which day according to when postriders arrived with weekly newspapers from other towns. They allowed just enough time to select and reprint news updates, editorials, and letters about current events. None, however, published their weekly newspaper on Sundays. Some occasionally distributed supplements or postscripts at some point during the week, but not on Sundays. That made Crouch’s South-Carolina Gazette Extraordinary for “SUNDAY EVENING, June 9, 1775” truly extraordinary. The Adverts 250 Project has so far examined advertising from January 1, 1766, through July 9, 1775. I believe this is the first advertisement from a newspaper published on a Sunday included in the project in nearly a decade.

What prompted Crouch to rush to press with a broadside edition printed on only one side of the sheet? The Extraordinary included news of the Battle of Bunker Hill, including articles and letters that originated in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Newport, Rhode Island; and Philadelphia. The news filled two entire columns and spilled over into a second. A short update with borders composed of ornamental type to draw attention, ran just above the advertisements that accounted for half of the final column. Although the dateline, “CHARLES-TOWN, JULY 9,” suggested local news, it carried a grave update about recent events in Massachusetts. “LETTERS from Rhode-Island mention,” Crouch reported, “That there were only 1200 Provincials in the Engagement mentioned under the Cambridge Head, and near 5000 of the King’s Troops; and that the celebrated Dr. Jospeh Warren, was among the Slain of our Brethren” at the Battle of Bunker Hill. When Crouch decided to deliver that news as soon as he could after receiving it, he also disseminated advertisements that would not otherwise have circulated on a Sunday. Benfield advertised “SOAP and CANDLES as usual,” yet there was nothing usual about the Extraordinary that carried his advertisement.