What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Some of the above-mentioned Lawns and Gauzes are perhaps the most genteel of any ever imported into North-America.”

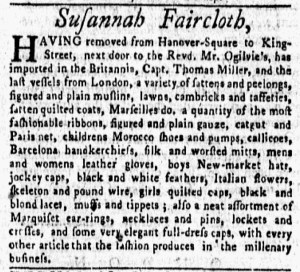

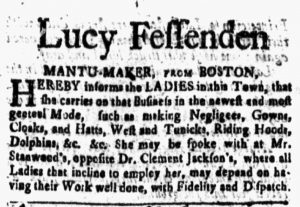

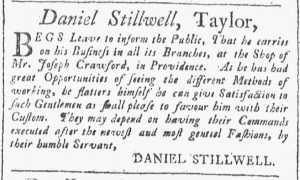

Several merchants and shopkeepers placed advertisements promoting imported goods in the December 10, 1771, edition of the Essex Gazette. With the exception of the notice from John Cabot and Andrew Cabot with its text running upward diagonally, most of those advertisements looked quite similar at a glance. The name of the purveyor of the goods, set in a larger font, functioned as a headline, an introduction outlined the origins of the merchandise and the location of the shop or warehouse, and dozens of items appeared in a catalog of current inventory.

Some advertisers, however, attempted to distinguish their notices from others by incorporating additional appeals to prospective customers. John Andrew, for instance, informed readers that they could expect good bargains at his shop at the Sign of the Gold Cup. “Those who favour him with their Custom,” he confided, “may depend upon being served with good Pennyworths, as he is determined to be undersold by none.” Elsewhere on the same page, Samuel Cottman described his prices as “Extremely cheap,” while John Gould and Company declared that they set prices “as low as at any Store in the Province.” Andrew made it clear that customers could expect competitive prices from him.

Rather than price, John Grozart made an appeal to fashion in the nota bene that enhanced his advertisement. He drew attention to certain textiles, declaring that “Some of the above-mentioned Lawns and Gauzes are perhaps the most genteel of any ever imported into North-America.” Those fabrics were not merely fashionable, Grozart suggested, but superlative in their fashionableness. Customers could not go wrong in purchasing them, especially if they wanted to impress their friends and acquaintances. Folsom and Hart advertised wigs “made in the present Taste,” but did not make claims nearly as bold as Grozart did about his wares as he attempted to incite curiosity among readers.

Neither Andrew nor Grozart included images in their advertisements. The copy had to do all the work of enticing prospective customers to visit their stores. To that end, they each devised an additional appeal to enhance the otherwise standard format of their newspaper notices, trusting that consumers practiced the close reading necessary to detect the differences among the advertisements in the Essex Gazette.