What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

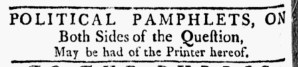

“POLITICAL PAMPHLETS, ON Both Sides of the Question.”

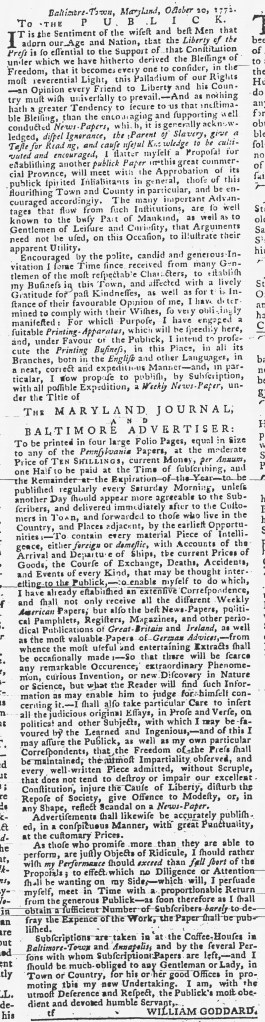

When he launched the Pennsylvania Ledger in the winter of 1775, James Humphreys, Jr., distributed proposals declaring that it would be a “Free and Impartial News Paper, open to All, and Influenced by None.” With high hopes for operating an impartial press as the imperial crisis intensified, he soon advertised “POLITICAL PAMPHLETS … on Both Sides of the Question” in February 1775. Several months later, he ran a notice advising that “POLITICAL PAMPHLETS, ON Both Sides of the Question, May be had of the Printer hereof” in the May 20 edition. Doing so required both courage and commitment, especially considering recent events.

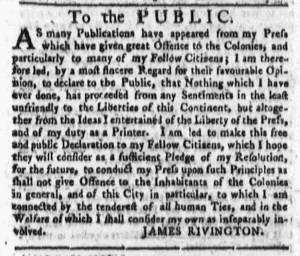

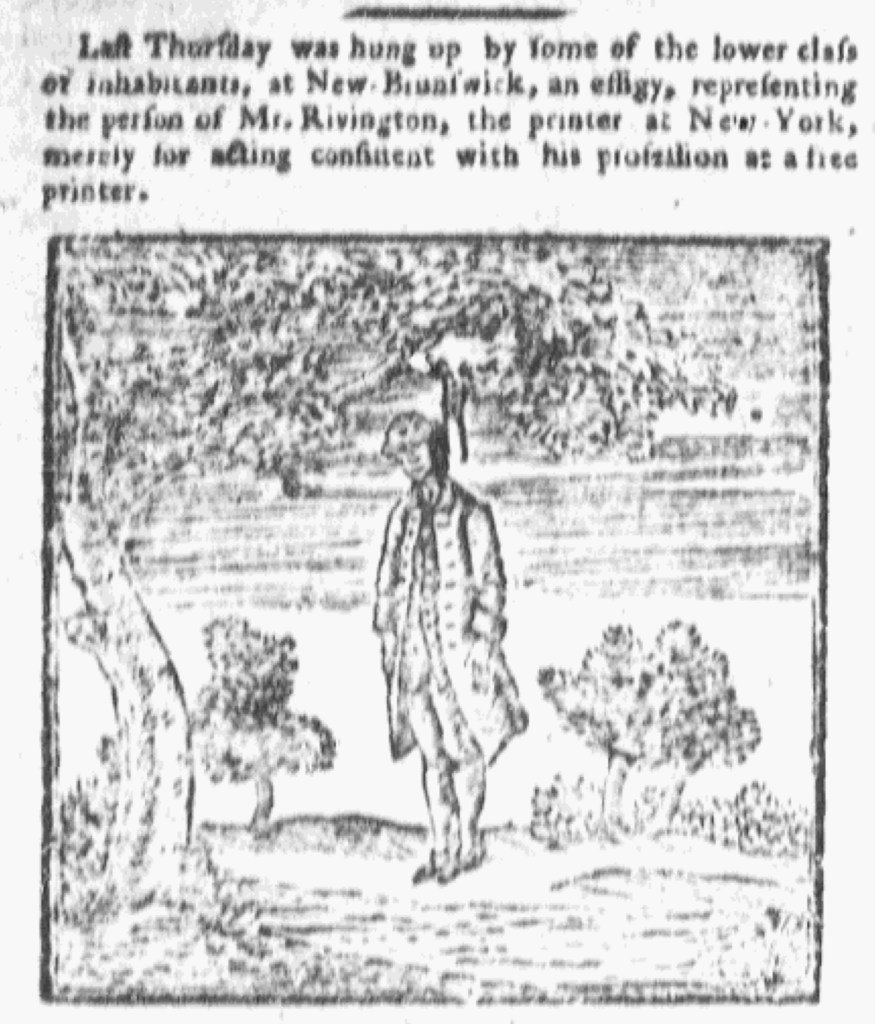

Humphreys published that advertisement a month after the battles at Lexington and Concord. The siege of Boston continued, yet he did not allow news of the battles or the siege to dissuade him from hawking pamphlets on “Both Sides of the Question.” Perhaps more significantly, James Rivington, the printer who also published pamphlets “on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain” at his “OPEN and UNINFLUENCED PRESS” in New York, had been hung in effigy in New Brunswick, New Jersey, by colonizers dissatisfied with what they considered his Loyalist sympathies. Rivington covered that event in his newspaper, Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, even including a woodcut depicting the scene. Given that printers exchanged newspapers with their counterparts in other cities and towns, Humphreys likely read about the effigy; even if he did not, he almost certainly heard about it. Even more recently, Rivington published a notice in which he acknowledged that “many Publications have appeared from my Press which have given great Offence … to many of my Fellow Citizens,” asserted that “Nothing which I have ever done, has proceeded from any Sentiments in the least unfriendly to the Liberties of this Continent,” and pledged “to conduct my Press upon such Principles as shall not give Offence to the Inhabitants of the Colonies.” Despite his effort to clarify that he had not pursued a political agenda but instead followed his “duty as a Printer” to encourage “the Liberty of the Press,” the Sons of Liberty attacked his home and office on May 10. Rivington took refuge on a British naval vessel. Assistants continued publishing the newspaper, inserting his notice about his true intentions twice more. Rivington had already discontinued advertising political pamphlets representing both sides of what he had previously called “The American Controversy” and “THE AMERICAN CONTEST.”

Although Humphreys advertised political pamphlets from “Both Sides” on May 20, word of what happened to Rivington may have prompted him to reconsider his courage in the weeks and months that followed. He discontinued that advertisement. In the next issue, he marketed only one pamphlet for sale at his printing office, The Group, a satire by Mercy Otis Warren that depicted a “SCENE AT BOSTON.” That publication unabashedly supported the American cause. A week later, that advertisement appeared on the first page of the Pennsylvania Ledger (as it had in the May 20 edition that carried the advertisement for political pamphlets on the final page), next to an advertisement for a multi-volume set of Political Disquisitions recommended for “all the friends of Constitutional Liberty, whether Britons or Americans.” Still, the editorial perspective of the Pennsylvania Ledger, according to Isaiah Thomas, “was under the influence of the British government” and Humphreys eventually “refused to bear arms in favor of his country, and against the government of England.”[1] He experienced sufficient difficulty that he suspended the newspaper at the end of November 1776. In May 1775, a year and a half earlier, he grappled with what kinds of publications he would promote among the advertisements in his newspaper, first forging ahead with notices for pamphlets representing multiple perspectives and then emphasizing those that supported the American cause, perhaps doing so in hopes of avoiding the treatment that Rivington received.

**********

[1] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 398.