What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

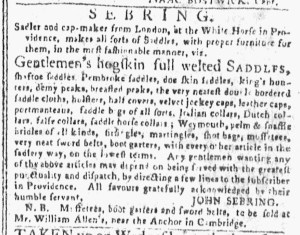

“SEBRING, Sadler and cap-maker from London, at the White Horse in Providence.”

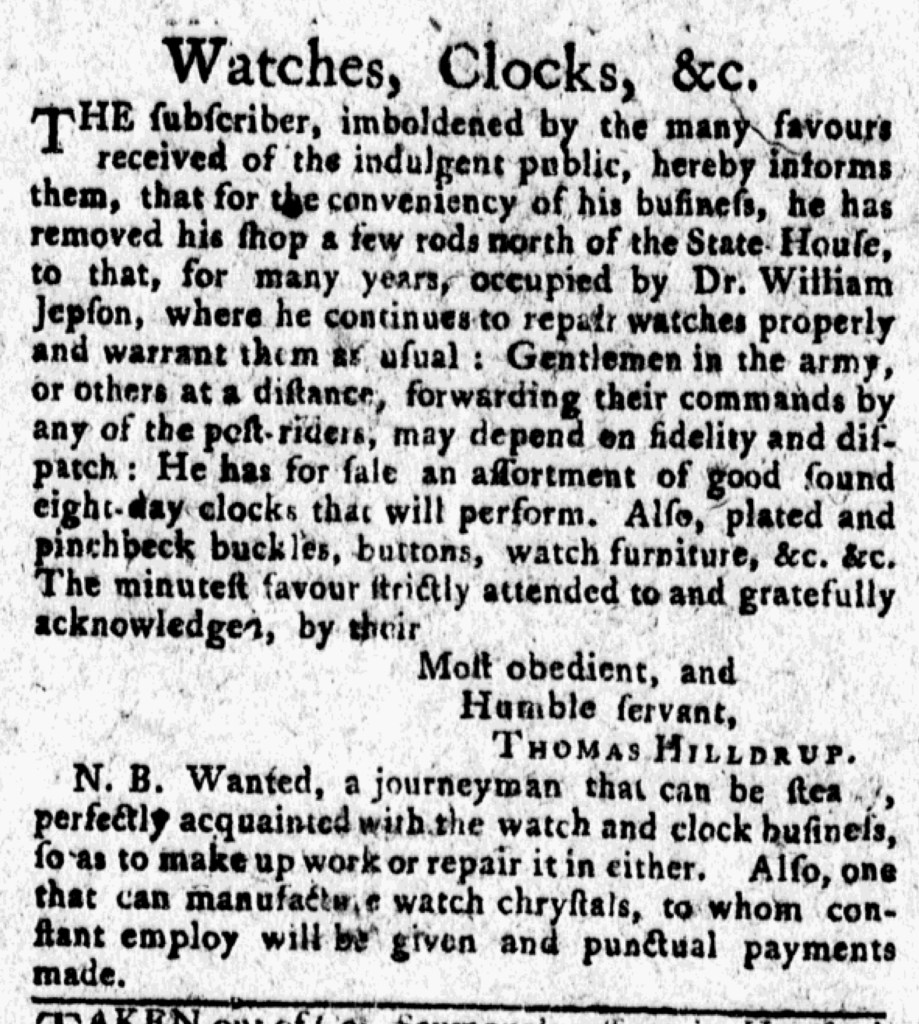

After migrating to the colonies from England in the early 1770s, John Sebring occasionally placed advertisements in the Providence Gazette, offering his services as a “Saddler, Chaise and Harness Maker.” Though he remained in Providence at the beginning of the Revolutionary War, he saw an opportunity to advertise in the New-England Chronicle, printed in Cambridge, in January 1776. As the siege of Boston continued, he introduced himself to readers as a “Sadler and cap-maker from London.” Even though it had been more than three years since he left the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the British Empire, he continued to stress his connection to it. Prospective customers, after all, associated both skill and taste with artisans who had trained in London or gained experience working there. Sebring also deployed one of the signature elements of his advertisements, using solely his surname rather than his full name as the headline. That initial proclamation, the mononym “SEBRING,” suggested celebrity and an established reputation.

In this advertisement, Sebring declared that he “Makes all sorts of Saddles, with proper furniture for them, in the most fashionable manner.” Practical was good, but stylish was even better! He listed a variety of items that he made “at the White Horse in Providence,” the location featured in his newspaper notices since he first began advertising, and then advised that “Any gentleman wanting any of the above articles may depend on being served with the greatest punctuality and dispatch, by directing a few lines” to him. Sebring had previously confined his advertisements to the Providence Gazette, but he apparently believed that the disruptions of the war opened new markets to him. American officers and soldiers gathered in Cambridge and nearby towns, many of them dispatched from distant places. As they would have been unfamiliar with local artisans, Sebring presented his workshop to supply saddles and other equipment via a mail order system. In a nota bene at the conclusion of the advertisement, he offered a chance to examine some of his wares before placing orders for customized items. “Mussetees [or musette bags, lightweight knapsacks used by soldiers], boot garters and sword belts,” Sebring stated, “to be sold at Mr. William Allen’s, near the Anchor in Cambridge.” Sebring apparently recruited a local agent to help him break into a new market.

**********

Clarification: Readers of the New-England Chronicle did not encounter this advertisement in the issue distributed on January 4, 1776. It should not have been the featured advertisement on January 4, 2026. Here’s how the mistake happened.

The format for the date in the masthead of some colonial newspapers confuses modern readers. That’s because some newspapers published weekly did not state only the date on which the newspaper was published but instead indicated the week that it covered. The New-England Chronicle was one of those newspapers. Rather than giving “January 4, 1776” as the date, the masthead for that issue stated, “From THURSDAY, Decem. 28, 1775, to THURSDAY, January 4, 1776.” For the issue published on January 11, the masthead stated, “From THURSDAY, January 4, to THURSDAY, January 11, 1776.”

While America’s Historical Newspapers associates the correct publication date with the issues of the vast majority of newspapers in the database, a couple newspapers use the date for the beginning of the week rather than the publication date. When an undergraduate research assistant downloaded digital copies of all American newspapers published in 1776, I neglected to warn him that was the case for the New-England Chronicle. I compounded the error by not looking at the masthead closely enough when I consulted the issue for January 4-11 to select an advertisement to feature on January 4. I only noticed the problem after publishing the entry.

Since advertisements for consumer goods and services typically ran for multiple weeks, I hoped that Sebring’s advertisement also appeared in the December 28 – January 4 issue. If that had been the case, I would have simply cropped the image from that issue and substituted it in this entry. However, Sebring’s notice made its first appearance in the January 4-11 issue.

I decided that the next best solution was updating the date in the citation that accompanies the image of Sebring’s advertisement and adding this clarification. It provides insight into the process of conducting research with digitized sources … and a warning about the importance of attention to detail. I have more than a decade of experience working with digitized eighteenth-century newspapers. I initially saw what I expected to see, not what was actually there, and only discovered the error when I took a closer look at the newspapers as I continued production of this project. Fortunately, I caught the error quickly and updated the filenames for the downloaded newspapers accordingly. In addition to this clarification, I am also making small adjustments to the Slavery Adverts 250 Project to adhere to the dates advertisements about enslaved people were published in the New-England Chronicle.