What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Fechtman undertakes to make stays and negligees, gowns and slips, without trying, for any lady in the country.”

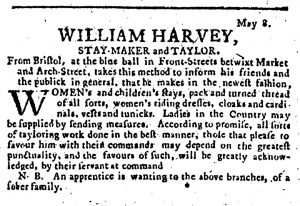

Christopher Fechtman, a “STAY and MANTUA-MAKER from LONDON,” promoted his services in an advertisement in the supplement to the December 29, 1767, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. After noting his change of address, he launched several appeals intended to incite demand for his services and instill a preference for obtaining stays, mantuas, and other items from him rather than his competitors.

Fechtman offered a guarantee of sorts, pledging to “give entire satisfaction to those who favour him” with their patronage. He did so with confidence, underscoring his own “knowledge of the business.” Yet Fechtman did not labor alone in his shop. He also employed “some experienced hands, who understand their business to the utmost dexterity.” Artisans commonly noted their skill and expertise in eighteenth-century advertisements. Fechtman assured potential customers that his subordinates who might have a hand in producing their garments were well qualified for the task. He staked his own reputation on that promise.

The staymaker also proclaimed that he would “work at a lower rate than any heretofore,” hoping to entice prospective clients with lower prices. High quality garments produced by skilled workers did not necessarily have to be exorbitantly expensive. Quite the opposite: Fechtman indicated that his prices beat any his competitors had ever charged.

Finally, Fechtman offered his services to women who resided in Charleston’s hinterland, widening his market beyond those who could easily visit his shop on Union Street while they ran other errands around town. To that end, he played up the convenience of procuring his services, noting that he could “make stays and negligees, gowns and slips, without trying, for any lady in the country.” His female clients did not need to visit his shop for a fitting. Presumably they forwarded their measurements when submitting their orders from a distance; tailors and others who made garments sometimes included instructions to send measurements with orders in their advertisements.

Fechtman competed with other stay- and mantua-makers in Charleston, a busy port city. To distinguish his garments and services from the competition, he resorted to several marketing strategies in his advertisement. He emphasized skill and expertise, both his own and that of the “experienced hands” who labored in his shop. He also offered low prices as well as convenience to clients unable to visit his shop for fittings. In the process, he encouraged prospective clients to imagine acquiring “stays and negligees, gowns and slips” from him, stoking demand and desire for his wares.