What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“All work sent home as soon as done by the return of post.”

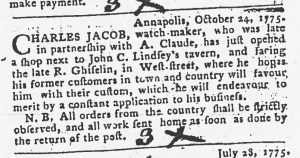

After his partnership with Abraham Claude ended, watchmaker Charles Jacob opened his own shop in Annapolis in the fall of 1775. He placed an advertisement in the Maryland Gazette in hopes that “his former customers in town and country will favour him with their custom,” though he also intended for the notice to draw the attention of new customers. Mentioning both his partnership with Claude and the clientele they had established demonstrated to prospective new customers that Jacob had the experience to serve them well. In addition, he pledged “constant application to his business” or, in other words, an industriousness that customers would find more than satisfactory.

For the convenience of customers who lived outside Annapolis, Jacob provided an eighteenth-century version of mail order service. In a nota bene, he stated that “orders from the country shall be strictly observed, and all work sent home as soon as done by the return of the post.” In other words, he gave the same attention to watches sent to him to clean or repair as if the customer had visited his shop. He did not give priority to customers who resided in Annapolis, nor did he delay returning watches to their owners when he finished working on them. Prospective customers did not need to worry that their watches might end up sitting on a workbench or tucked away in a drawer and forgotten while Jacob attended to other projects. Instead, he ran an orderly shop.

Jacob may have occupied the same location where he and Claude previously kept shop. In their earlier advertisements, including one in the October 1, 1773, edition of the Maryland Gazette, they gave their address as “opposite Mr. Ghiselin’s, in West-Street. In his new advertisement, Jacob declared that he “has just opened a shop next to John C. Lindsey’s tavern, and facing the late R. Ghiselin, in West-street.” A familiar location may have helped him retain some of the customers that frequented the shop when he ran it in partnership with Claude.