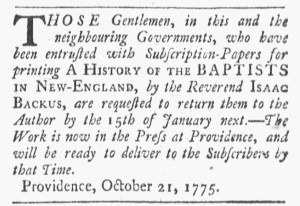

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“THOSE Gentlemen … who have been entrusted with Subscription-Papers … are requested to return them.”

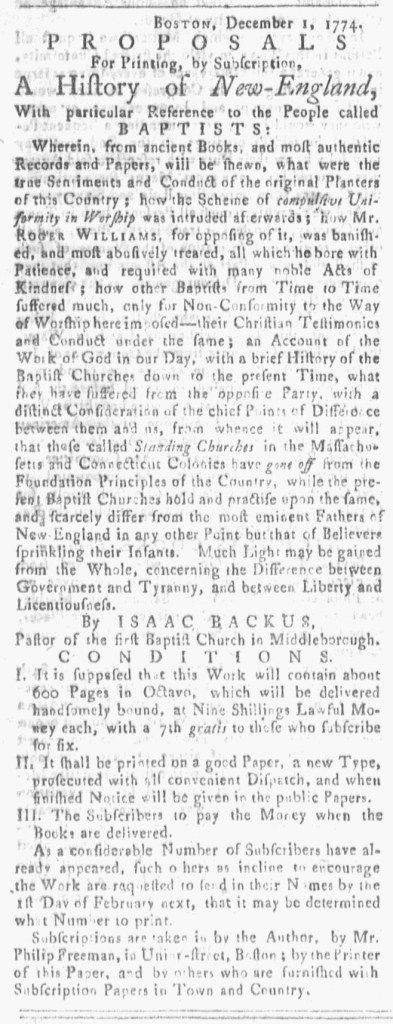

Among the various advertisements in the October 21, 1775, edition of the Providence Gazette, one requested that “THOSE Gentlemen, in this and the neighbouring Governments [or colonies], who have been entrusted with Subscription-Papers for printing A HISTORY OF THE BAPTISTS IN NEW-ENGLAND … return them to the Author,” Isaac Backus, “by the 15th of January next.” Backus, a Baptist minister, advocate for religious liberty, and one of the founders of Rhode Island College (now Brown University), previously announced this project in an advertisement in the Providence Gazette ten months earlier in December 1774. At that time, he indicated that “Subscriptions are taken in by the Author, by Mr. Philip Freeman, in Union-street, Boston; by the Printer of this Paper, and by others who are furnished with Subscription Papers in Town and Country.”

Like many other authors and printers, neither Backus nor John Carter, the “Printer of this Paper” who apparently planned to publish the History, went to press without first having an idea how many copies to produce to make the venture viable. They disseminated subscription proposals to garner interest, asking those who wished to reserve copies to sign the subscription papers entrusted to local agents in their towns. The combination of subscription proposals and subscription papers served two important functions, inciting demand and gauging the market. Despite that level of sophistication, Backus did not write directly to the local agents who oversaw the subscription papers “in Town and Country” but instead ran a newspaper advertisement and expected local agents to see it and respond according to the directions in the notice.

Backus originally instructed that prospective subscribers should “send in their Names” by February 1, 1775, “that it may be determined what Number to print,” but the project had stalled as the imperial crisis intensified. His new advertisement extended the deadline by nearly a year, though this time he reported that the “Work is now in the Press at Providence, and will be ready to deliver to the Subscribers by that Time.” That seems to have been another miscalculation since the first of three volumes did not appear until 1777, printed by Edward Draper in Boston rather than by Carter in Providence. The book had a circuitous path to publication. Backus attempted to use newspaper advertisements to keep subscribers informed, but factors beyond his control intervened.