What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

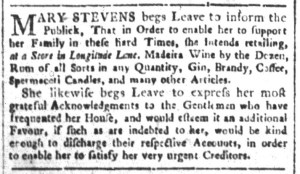

“In Order to enable her to support her Family in these hard Time, she intends retailing … Gin, Brandy, Coffee.”

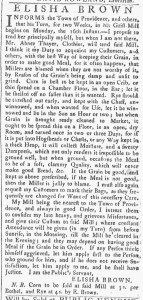

Women regularly advertised goods and services in early American newspapers. Mrs. Miller, a milliner, for instance, ran an advertisement in the August 18, 1775, edition of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette. Like many advertisements placed by female entrepreneurs, it did not differ from others placed by their male counterparts. Mary Stevens also placed an advertisement in the same issue of that newspaper, though she deployed a marketing strategy more often used by women than by men. She announced that she planned to open a store to retail wine, rum, gin, brandy, coffee, candles, and “many other Article.” She did so, she declared, “in Order to enable her to support her Family in these hard Times.” Rather than promote the quality or variety of her wares or promise exemplary customer service, some of the most common marketing strategies of the era, Stevens made her ability to support her family the primary reason that prospective customers should visit her store. Many readers would have known more details than Stevens revealed in her advertisement, details that would have made her even more sympathetic.

Whatever her circumstances, Stevens had apparently conducted another sort of business for some time. She devoted the second half of her advertisement to expressing “her most grateful Acknowledgments to the Gentlemen who have frequented her House.” Again, many readers would have known whether Stevens took in boarders or prepared meals or served coffee in the parlor while her patrons discussed business and current events. She served those “Gentlemen” on credit, but “these hard Times” made it necessary to ask them to “discharge their respective Accounts, in order to enable her to satisfy her very urgent Creditors.” Men very often placed newspaper notices that called on associates to settle accounts, but rarely did they invoke the urgency that Stevens conveyed in her advertisement. Even more rarely did they refer to supporting their families. As a woman in business, Stevens may have been able to exercise a small amount of privilege in framing her advertisement in this manner, though the necessity that led her to do so did not suggest that she benefited from many advantages when it came to participating in the marketplace.