What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“An Elegy to the memory of the American Volunteers who fell … April 19, 1775.”

During the era of the American Revolution, advertisements for almanacs frequently appeared in newspapers from New England to Georgia each fall. Such was the case in the Pennsylvania Journal in 1775. James Adams, a printer in Delaware, inserted a notice that announced that he “JUST PUBLISHED … The WILMINGTON and PENNSYLVANIA ALMANACKS, For the year of our LORD, 1776.”

Adams followed a familiar format for advertising almanacs. He indicated that both editions included “the usual astronomical calculations” that readers would find in any almanac as well as a variety of other enticing contents. The Pennsylvania edition included “Pithy Sayings” for entertainment and “Tables of Interest at six and seven per cent” for reference as well as the “Continuation of William Penn’s Advice to his Children” and the “Conclusion of Wisdom’s Call to the young of both sexes.” Adams published a portion of those pieces in the almanac for the previous year, anticipating that readers would purchase the subsequent edition for access to the essays in their entirety. The almanac for 1776 also suggested “Substitutes for Tea,” certainly timely considering that the Continental Association remained in effect. Colonizers sought alternatives while they boycotted imported tea.

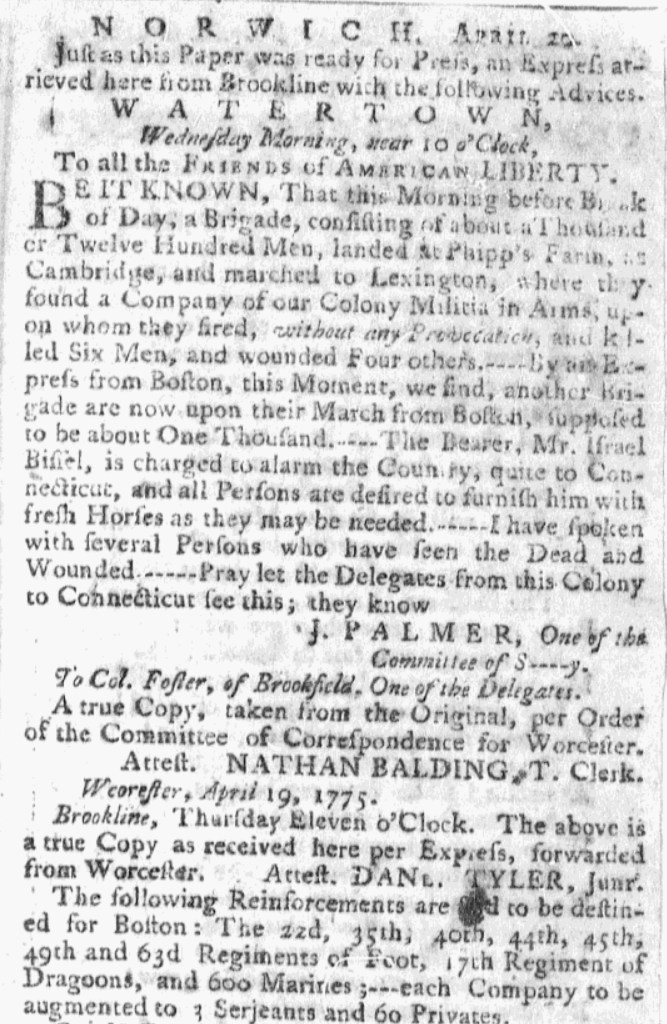

Current events played an even more prominent role in the Wilmington Almanack. It featured an “Elegy to the memory of the American Volunteers, who fell in the engagement between the Massachusetts-Bay Militia and the British Troops, April 19, 1775.” Six months after the battles at Lexington and Concord, Adams memorialized the minutemen who had died for the American cause during the first battles of the Revolutionary War. In addition, the almanac featured “The Irishman’s Epistle to the Officers and troops at Boston,” “Liberty-Tree,” and “A droll Dialogue between a fisherman of Poole, in England, and a countryman, relative to the trade of America, and proposed victory over the Americans.” Adams did not elaborate on those items, perhaps intentionally. Presenting the titles of the pieces without further elaboration was standard practice in advertisements for almanacs, but in this case the printer may have intended to stoke curiosity that would lead to more sales. For both almanacs, a concern for current events and a burst of patriotism influenced the contents and their marketing.