What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

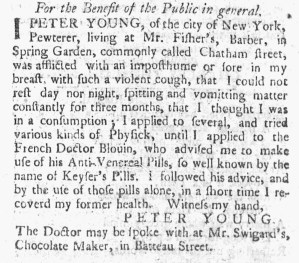

“I applied to the French Doctor Blouin, who advised me to make use of his Anti-Venereal Pills.”

Peter Young, a pewterer in New York, went through quite an ordeal. According to the advertisement he placed in the January 17, 1776, edition of the Constitutional Gazette, he “was afflicted with an imposthume or sore in my breast, with such a violent cough, that I could not rest day or night.” In addition, he was “spitting and vomitting matter constantly for three months,” so much so that he thought he “was in a consumption.” Young sought out medical assistance from several providers and “tried various kinds of Physick,” but none of them could alleviate the disorder that he suffered … at least not until he “applied to the French Doctor Blouin.” That doctor advised Young “to make use of his Anti-Venereal Pills, so well known by the name of Keyser’s Pills.” The pewterer followed Blouin’s advice and “by the use of those pills alone, in a short time [he] recovered [his] former health.”

According to the advertisement’s header, Young inserted his testimonial in the Constitutional Gazette “For the Benefit of the Public in general.” Beneath his signature, a note advised, “The Doctor may be spoke with at Mr. Swigard’s, Chocolate Maker, in Batteau Street.” The advertisement gave no indication about who added that note. It could have been Young or it could have been John Anderson, the printer of the Constitutional Gazette, out of his own desire to assist the public. Most likely, Blouin added that detail and engineered publishing the testimonial while seeking to make it appear that Young published it independently. After all, if Young pursued that course on his own, solely “For the Benefit of the Public in general,” that made the recommendation even more noteworthy for readers who hoped for relief from similar symptoms. Blouin previously placed advertisements in the Constitutional Gazette, introducing himself and his pills “TO THE PUBLIC.” Young’s testimonial supplemented his previous marketing efforts.