What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“THE MODERN RIDING-MASTER … Adorned with sixteen neat engravings.”

When Robert Aitken “PUBLISHED, PRINTED and SOLD” an American edition of Philip Astley’s “THE MODERN RIDING-MASTER, or a KEY to the KNOWLEDGE of the HORSE and HORSEMANSHIP,” he placed an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Evening Post. In marketing the manual, he emphasized Astley’s celebrity, identifying him as a “Riding-master, late of his Majesty’s royal light dragoons.” Aitken also promised that the manual included “several necessary rules for young horsemen.” To that end, he declared that The Modern Riding-Master “may be considered as an useful Vade-Mecum” or handbook “for gentlemen of every rank and profession, whether civil or military.” As printers and booksellers often did in their advertisements, Aitken copied the section headings to provide an overview of the contents. The manual began with “Necessary precautions in purchasing a horse” and attention “Of the bridle and saddle,” continued with “The art of riding, and reducing a horse to proper obedience,” and also covered how “To mount the horse; with a variety of directions for the training and better government of this useful animal” and “Necessary directions on a journey.”

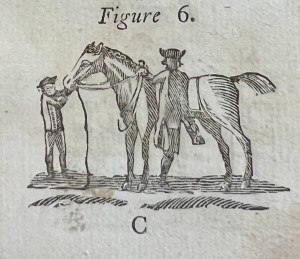

In addition to these directions, the manual featured “sixteen neat engravings descriptive of this manly exercise.” Aitken exaggerated a bit. The handbook did indeed have sixteen illustrations, but they were woodcuts integrated into the text rather than copperplate engravings printed separately. Those images “Adorned” the text, as Aitken stated, but they were not of the same quality as engravings. Still, they provided useful visual aids for readers. To draw the attention of prospective customers, Aitken submitted one of those woodcuts, Figure 6, to accompany his advertisement in the Pennsylvania Evening Post. It depicted a rider placing his “left Foot in the Stirrup” as he prepared to mount a horse held steady by an attendant. Aitken made savvy use of the woodcut, reusing it in an advertisement once he finished printing the manual. It was the only visual image in his notice in the Pennsylvania Evening Post, a newspaper that did not even have a device in its masthead. The woodcut gave a preview of what readers could expect if they purchased Astley’s manual.