What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A General and compleat assortment of muffs and tippets in the newest taste.”

As winter approached in 1774, Lyon Jonas, a “FURRIER, from LONDON,” took to the pages of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury to advertise the “General and compleat assortment of muffs and tippets in the newest taste” available at his shop on Little Dock Street. He also “manufactures and sells gentlemens caps and gloves lined with furr, very useful for travelling,” “trims ladies robes and riding dresses,” and “faces and lappels gentlemens coats and vests.” In addition to those services, Jonas “buys and sells all sorts of furrs, wholesale and retail.”

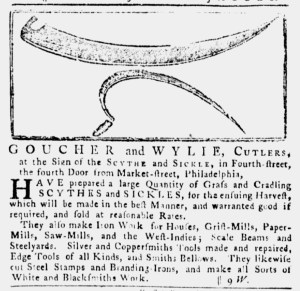

To attract attention to his advertisement, the furrier adorned it with a woodcut that depicted a muff and a tippet (or scarf) above it with both enclosed within a decorative border. It resembled, but did not replicate, the woodcut that John Siemon included in his advertisements in the New-York Journal, the Pennsylvania Chronicle, and the Pennsylvania Journal three years earlier. That image did not include a border, but perhaps whoever carved Jonas’s woodcut recollected it when the furrier commissioned an image to accompany his notice.

Whatever the inspiration may have been, Jonas’s woodcut represented an additional investment in his marketing efforts. First, he paid for the creation of the image. Then, he paid for the space it occupied each time it appeared in the newspaper. Advertisers paid by the amount of space rather than the number of words. The woodcut doubled the amount of space that Jonas required in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, incurring additional expense. Jonas presumably considered it worth the cost since the woodcut distinguished his notice from others. In the November 21 edition and its supplement, five other advertisements featured stock images of ships and Hugh Gaine, the printer, once again ran an advertisement for Keyser’s “Famous Pills” with a border composed of ornamental type. Beyond that Jonas’s notice was the only one with an image as well as the only one with an image depicting an aspect of his business and intended for his exclusive use. Readers could hardly have missed it when they perused the pages of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury.