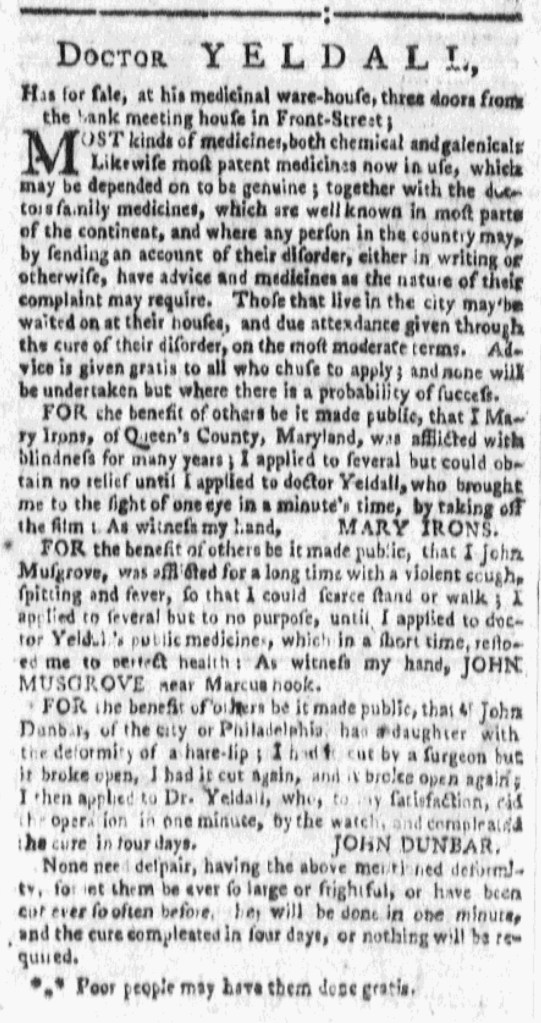

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“The doctors family medicines, which are well known in most parts of the continent.”

Doctor Yeldall ran his advertisement for remedies available “at his medicinal ware-house” on Front Street in Philadelphia in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer at the same time that it appeared in the Pennsylvania Ledger. He did, after all, claim that the “doctors family medicines” that he produced as an alternative to other patent medicines were “well known in most parts of the continent” and advised that “any person in the country may, be sending an account of their disorder … have advice and medicines as the nature of their complaint may require.” Yeldall operated the eighteenth-century version of a mail order pharmacy. Advertising in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer: Or, the Connecticut, Hudson’s River, New-Jersey, and Quebec Weekly Advertiser placed his notice before the eyes of many more prospective patients. In addition to selling medicines, Yeldall also performed medical procedures. Two of the four testimonials in the original advertisement described restoring sight “by taking off the film” from a patient’s eye and repairing “the deformity of a Hare-Lip.” New York was close enough to Philadelphia that Yeldall may have expected that some prospective patients who exhausted their options in one place would travel to Philadelphia in hopes that he would successfully treat them.

The advertisements in the two newspapers were nearly identical. The use of capital letters and italics varied, likely the result the decisions made by compositors in the two printing offices. That was usually the case when advertisers submitted the same copy to multiple newspapers. The version in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer lacked the longest of the four testimonials that ran in the Pennsylvania Ledger. The compositor might have removed Alexander Martin’s description of how Yeldall “recovered me to my perfect health” after being “afflicted with a consumptive disorder for upwards of three years” in the interest of space. Yeldall’s advertisement ran at the bottom of the final column on the third page of the June 22, 1775, edition of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, making it one of the last items inserted during the production of that issue. The compositor, lacking space for the entire advertisement, may have simply removed one of the testimonials. The notice still made the point that Yeldall supposedly cured several patients who “could obtain no relief” until they sought medical care from him.