What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“He will publish No. I. of a News-Paper … THE NEW-YORK PACKET; OR THE AMERICAN ADVERTISER.”

The American Revolution resulted in an explosion of print. The disruptions of the war led to the demise of some newspapers, but others continued, joined by new publications during the war and, especially, even more newspapers after the war ended. The major port cities had one or more newspapers before the Revolutionary War. Many minor ports also had a newspaper. Once the new nation achieved independence, printers commenced publishing newspapers in many more towns. Thoughtful citizenship depended in part on the widespread dissemination of news. Samuel Loudon’s New York Packet was part of that story.

In December 1775, Loudon announced that he “will publish No. I. of a News-paper, (To be continued weekly)” on Thursday, January 4. He initially advertised in other newspapers printed in New York, but by the end of the month others carried his proposals, including the Connecticut Journal, published in New Haven, and the Pennsylvania Gazette, published in Philadelphia. Newspapers circulated far beyond their places of publication. Printers wanted them to supply content for their own newspapers. The proprietors of coffeehouses and taverns acquired them for their patrons. Merchants used them for updates about both commerce and politics. Loudon had a reasonable expectation of attracting subscribers beyond New York. A nota bene at the end of his advertisement in the Connecticut Journal noted that “Subscriptions [were] taken by the Printers, and all the Post Riders,” a network of local agents that assisted in distributing Loudon’s newspaper.

To entice potential subscribers, Loudon explained that he “is encouraged to undertake this arduous work by the advice and promised literary assistance of a numerous circle of warm friends to our (at present much distressed) country.” That signaled to readers that Loudon supported the American cause. It also offered assurances that he had the means to acquire sufficient content to publish a weekly newspaper. To that end, Loudon pledged “to do everything in his power to render it a complete and accurate NEWS-PAPER, that the Public may thereby receive the earliest intelligence of the state of our public affairs, and of the several interesting occurrences which may occasionally happen whether at home or abroad.” In the spirit of newspaper providing the first draft of history, the printer declared that he “flatters himself that the NEW YORK PACKET, will influence every discerner of real merit, who may encourage the work, to preserve it in volumes, as a faithful Chronicle of our own time.”

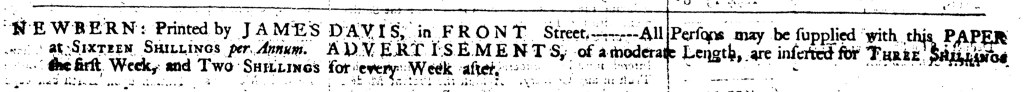

In addition to expressing such ideals, Loudon also tended to the business aspects of establishing a newspaper. He reported that he “already possessed himself of a neat and sizeable set of TYPES … together with every other necessary for carrying on a splendid News Paper.” Soon enough, “the best of hands shall be procured to perform the mechanical part.” Subscribers could expect the New York Packet “will be printed … on a large Paper, of a good Quality, and equal in Size to the other News-Papers published in this City.” Subscriptions cost twelve shillings per year. Loudon also solicited advertisements, indicating that they “will be inserted at the usual Price of Five Shillings, when of a moderate Length, and continued Four Weeks.” As was the practice in other printing offices, “longer Advertisements to be charged accordingly.”

Loudon did indeed launch the New York Packet on January 4, 1776. It lasted only eight months in New York, suspended after the August 29 edition, as Clarence S. Brigham explains, “immediately prior to the entry of the British into New York. Loudon re-established the paper at Fishkill in January, 1777, and at the close of the War returned to New York.”[1] Without changing the volume numbering, he continued publishing the New York Packet from November 13, 1783, through January 26, 1792. By then, Loudon published the newspaper three times a week, part of that explosion of print that occurred during the era of the American Revolution. Shortly after closing the New York Packet, Loudon and his son, Samuel, established a daily newspaper, The Diary; or Loudon’s Register. Unfortunately, the issues of the New York Packet published in 1776 have not been digitized for greater access, though the run for 1783 through 1792 is available via Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers. That means that advertisements and other content from that newspaper will not be featured in the Adverts 250 Project, its story confined to the subscription proposals that ran in other newspapers.

**********

[1] Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820 (Worcester, Massachusetts: American Antiquarian Society, 1947), 675.