Isaiah Thomas, patriot printer and founder of the American Antiquarian Society, was born on January 19 (New Style) in 1749 (or January 8, 1748/49, Old Style). It’s quite an historical coincidence that the three most significant printers in eighteenth-century America — Benjamin Franklin, Isaiah Thomas, and Mathew Carey — were all born in January.

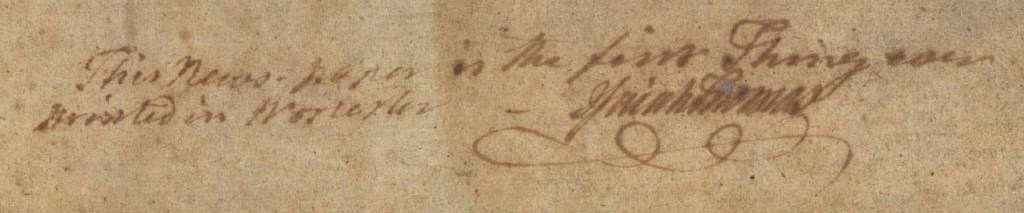

The Adverts 250 Project is possible in large part due to Thomas’s efforts to collect as much early American printed material as he could, originally to write his monumental History of Printing in America. The newspapers, broadsides, books, almanacs, pamphlets, and other items he gathered in the process eventually became the initial collections of the American Antiquarian Society. That institution’s ongoing mission to acquire at least one copy of every American imprint through 1876 has yielded an impressive collection of eighteenth-century advertising materials, including newspapers, magazine wrappers, trade cards, billheads, watch papers, book catalogs, subscription notices, broadsides, and a variety of other items. Exploring the history of advertising in early America — indeed, exploring any topic related to the history, culture, and literature of early America at all — has been facilitated for more than two centuries by the vision of Isaiah Thomas and the dedication of the curators and other specialists at the American Antiquarian Society over the years.

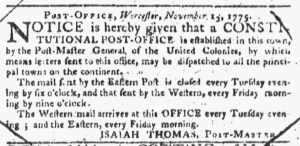

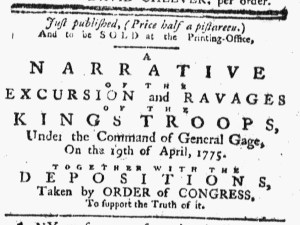

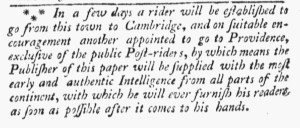

Thomas’s connections to early American advertising were not limited to collecting and preserving the items created on American presses during the colonial, Revolutionary, and early national periods. Like Mathew Carey, he was at the hub of a network he cultivated for distributing newspapers, books, and other printed goods — including advertising to stimulate demand for those items. Sometimes this advertising was intended for dissemination to the general public (such as book catalogs and subscription notices), but other times it amounted to trade advertising (such as circular letters and exchange catalogs intended only for fellow printers, publishers, and booksellers).

Thomas also experimented with advertising on wrappers that accompanied his Worcester Magazine, though he acknowledged to subscribers that these wrappers were ancillary to the publication: “The two outer leaves of each number are only a cover to the others, and when the volume is bound may be thrown aside, as not being a part of the Work.”[1]

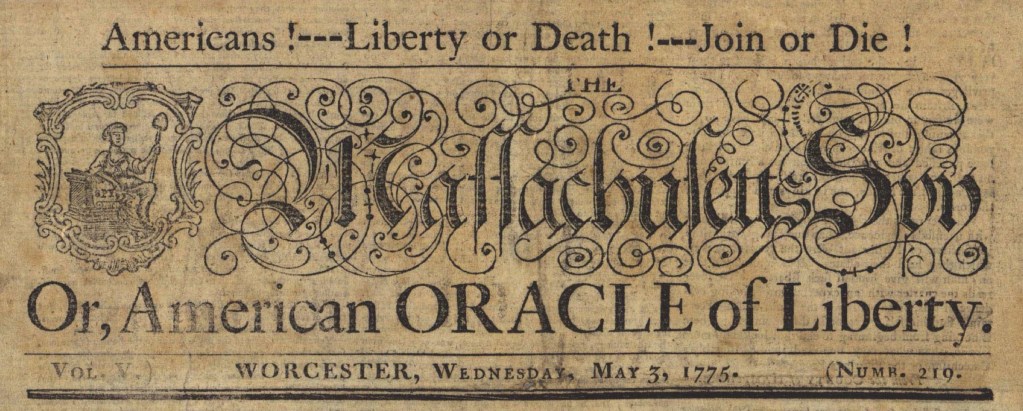

Thomas’s patriotic commitment to freedom of the press played a significant role in his decision to develop advertising wrappers. As Thomas relays in his History of Printing in America, he discontinued printing his newspaper, the Massachusetts Spy, after the state legislature passed a law that “laid a duty of two-thirds of a penny on newspapers, and a penny on almanacs, which were to be stamped.” Such a move met with strong protest since it was too reminiscent of the Stamp Act imposed by the British two decades earlier, prompting the legislature to repeal it before it went into effect. On its heels, however, “another act was passed, which imposed a duty on all advertisements inserted in the newspapers” printed in Massachusetts. Thomas vehemently rejected this law as “an improper restraint on the press. He, therefore, discontinued the Spy during the period that this act was in force, which was two years. But he published as a substitute a periodical work, entitled ‘The Worcester Weekly Magazine,’ in octavo.”[2] This weekly magazine lasted for two years; Thomas discontinued it and once again began printing the Spy after the legislature repealed the objectionable act.

Isaiah Thomas was not interested in advertising for its own sake to the same extent as Mathew Carey, but his political concerns did help to shape the landscape of early American advertising. Furthermore, his vision for collecting American printed material preserved a variety of advertising media for later generations to admire, analyze, ponder, and enjoy. Happy 277th birthday, Isaiah Thomas!

**********

[1] Isaiah Thomas, “To the CUSTOMERS for the WORCESTER MAGAZINE,” Worcester Magazine, wrapper, second week of April, 1786.

[2] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers, vol. 2 (Worcester, MA: Isaac Sturtevant, 1810), 267-268.