What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“WILL BE PUBLISHED … A JOURNAL OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS.”

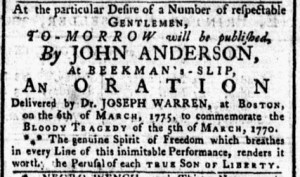

On Thursday, December 21, 1775, John Anderson, the printer of the Constitutional Gazette, ran an advertisement in the New-York Journal to stimulate interest in one of his forthcoming projects. “On SATURDAY NEXT,” he announced, “will be published, by JOHN ANDERSON … A JOURNAL OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS.” Just two weeks earlier, William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, the printers of the Pennsylvania Journal, advertised that they would soon publish the “JOURNAL OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONGRESS, HELD AT PHILADELPHIA, May 10, 1775.” It appears that Anderson quickly acquired a copy and set about printing a local edition for the New York market, making him the first printer outside of Philadelphia to publish an overview of the Second Continental Congress when it convened after the battles at Lexington and Concord. The volume that Anderson published had a slightly different title than what appeared in the advertisement: Extracts from the Votes and Proceedings of the American Continental Congress: Held at Philadelphia, 10th May, 1775. In the rush to take it to press, the compositor introduced several errors in the page numbers, according to the American Antiquarian Society’s catalog.

Neither the Bradfords nor Anderson merely printed these collections of records of the Second Continental Congress and then advertised them. Instead, both encouraged readers to anticipate their publication, making the eventual announcements that they were available for purchase even more enticing and persuasive. On Saturday, December 23, Anderson’s own newspaper featured an advertisement promising that “This Day will be published by the Printer. A Journal of the Proceedings of the Continental Congress.” Eager customers could visit his printing office “at Beekman’s-Slip” to see if copies were ready for purchase. By December 27, they were certainly available. In the issue of the Constitutional Gazette distributed that day, Anderson described the volume as “Just published by the Printer” and listed three local agents who also sold it. An updated advertisement also appeared in the New-York Journal on December 28, nearly identical to the one from the previous issue with the first two lines replaced with a single line. Anderson’s advertisement began, “Just published, and to be sold by” instead of “On SATURDAY NEXT / WILL BE PUBLISHED, by.” Using a series of advertisements in two of New York’s newspapers, Anderson announced the forthcoming publication of a local edition of “THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS” and kept the public informed of its progress and availability.