GUEST CURATOR: Nicholas Commesso

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

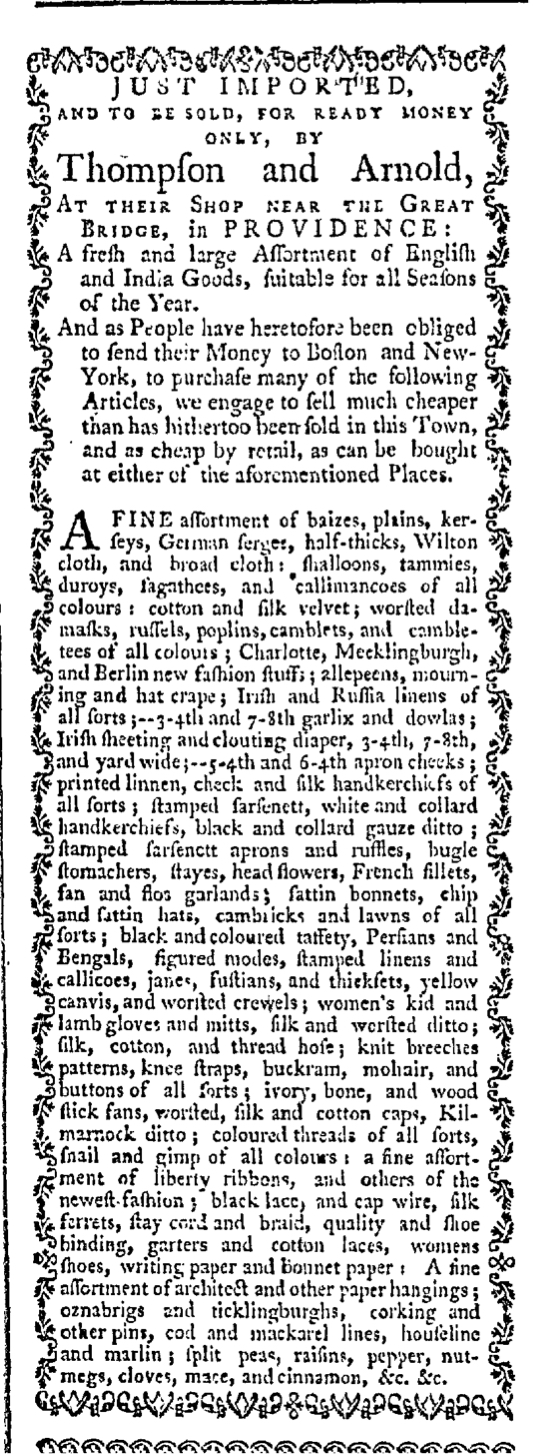

“A fresh and large Assortment of English and India Goods.”

This advertisement in the Providence Gazette features a lengthy list of newly imported goods at the shops of Thompson and Arnold. “TO BE SOLD, FOR READY MONEY ONLY,” these goods had been imported from both from England and India. Included in this “FINE assortment” were different textiles, clothing, and related items, such as “Irish and Russia linens of all sorts,” satin bonnets, shalloons, tammies, “colored threads of all sorts,” and countless other products. Why was importation so important? Business for the British was truly booming in colonial America. As T.H. Breen notes, newspapers “carried more and more advertisements for consumer goods,” and all Americans were a part of this “consumer revolution.”[1]

This shop clearly emphasized fashion, as they offered many different options in terms of colors and materials, which especially interested women. For women, shopping was an exhibition of liberty, and “with choice came a measure of economic power.” They had choices of products and choices of shops to visit. A variety of options allowed customers to gain leverage as they asked questions and made demands. Additionally, Breen argues, choice “reinforced the Americans’ already strong conviction of their own personal independence.”[2]

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

I originally intended to feature this advertisement a week ago today, but when Nick submitted the same advertisement (printed a week later) for approval I decided to hold off for a week. I figured that the chances were quite probable that he and I would approach the advertisement from very different perspectives, that discussion of this advertisement would be enhanced from both of us examining it.

That turned out to be the case. I initially selected this advertisement because I wanted to discuss its format. In some regards it looks quite similar to an advertisement previously published by Thompson and Arnold (which appeared for the first time in the August 9, 1766, issue of the Providence Gazette and then many more times in subsequent issues.) The original iteration of this advertisement deployed graphic design in several unique ways. It surely caught the attention of readers and potential customers.

This version of the advertisement reverted to some of the more standard aspects of eighteenth-century newspaper advertisements. In particular, it inhabited a single column within the issue, whereas the earlier version spanned two columns. The previous version also used three columns to delineate Thompson and Arnold’s merchandise, but in today’s advertisement their inventory collapsed into a dense list instead. This did not have the same visual resonance, nor did it make it as easy for potential customers to locate specific products of interest.

Still, the updated version of Thompson and Arnold’s advertisement featured design elements intended to continue drawing the eyes of readers. Like the previous version, it retained a decorative border made of printing ornaments. Very few newspaper advertisements in the 1760s had such borders (though we have previously seen that Jolley Allen made sure that his advertisements in Boston’s newspapers were easily identified by their borders). In addition, Thompson and Arnold’s advertisement was much longer than most that appeared in the Providence Gazette. Its size alone merited notice. Finally, today’s advertisement appeared in the first column of the first page of the Providence Gazette, right below the masthead. In design, layout, and location, there was no way for readers to overlook Thompson and Arnold’s updated advertisement.

**********

[1] T.H. Breen, “An Empire of Goods: The Anglicization of Colonial America, 1690-1776,” Journal of British Studies 25, no. 4 (October 1986): 486-487.

[2] Breen, “Empire of Goods,” 489.