Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“RUN away … a mulatto man, named GABRIEL.”

After taking out an advertisement in a competing newspaper on January 27, 1776, an apology for not publishing his Virginia Gazette because he had difficulty acquiring paper, John Pinkney managed to print the next issue on schedule on February 3. He may or may not have published subsequent issues, but today the February 3 edition is the last known one from his press. In his apology, Pinkney lamented, “It gives me the greatest Uneasiness that I cannot publish such Advertisements as ought to have appeared this Week.” The next (and perhaps final) issue included more than two dozen advertisements of various lengths on the last two pages.

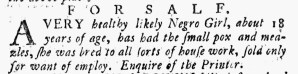

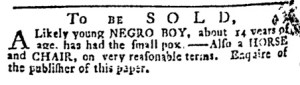

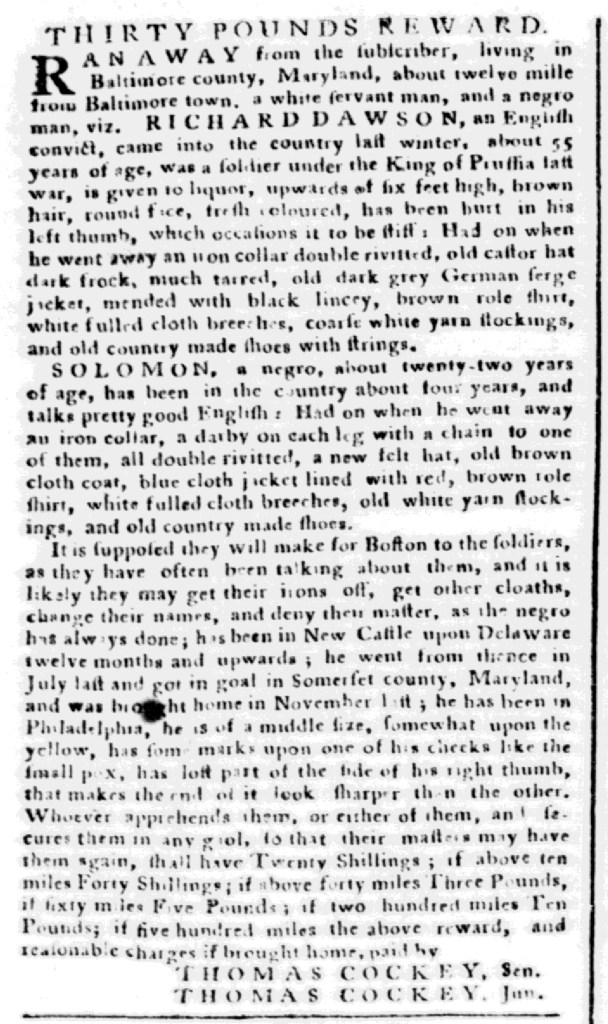

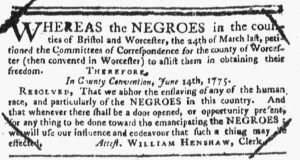

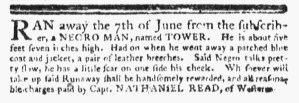

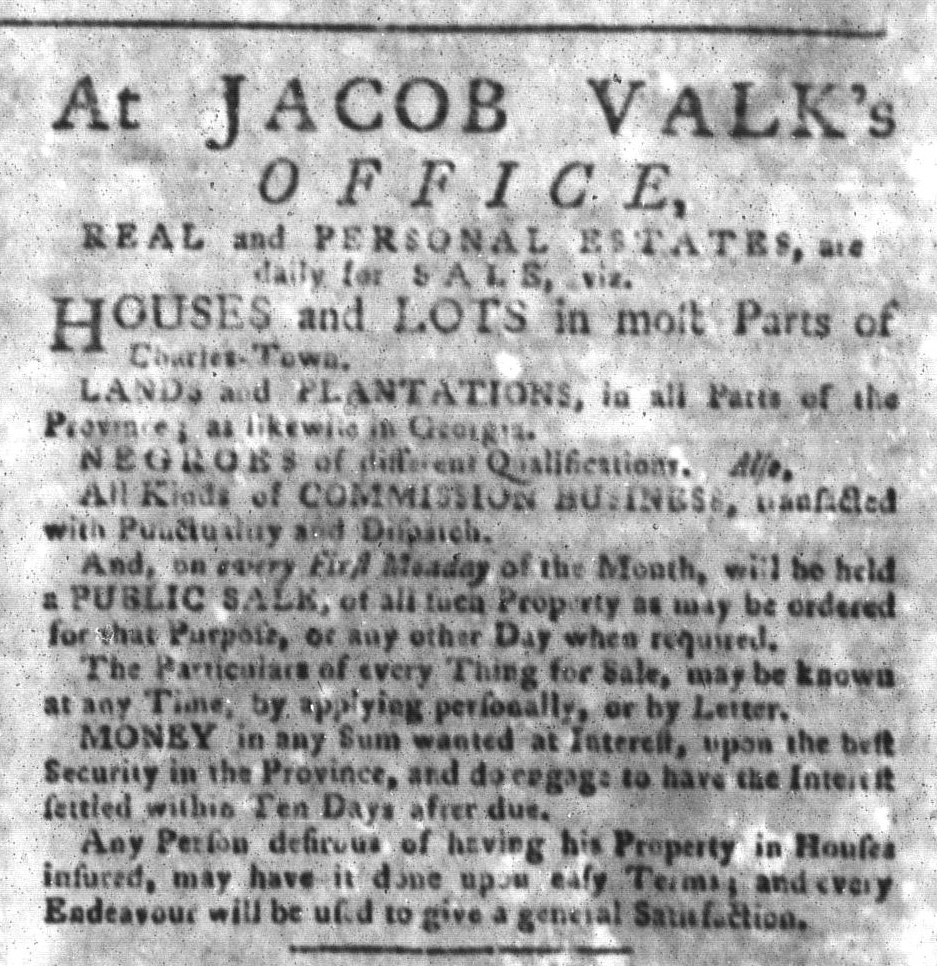

Among those advertisements, Julia Wheatley offered her services as a midwife, Carter Braxton and John Ware described real estate for sale, and Pinkney hawked “A TREATISE on the MILITARY DUTY, By adjutant DAVIS,” a pamphlet that “has met with the approbation of colonel BULLITT, and many other officers.” Six of those notices, accounting for one-quarter of the advertisements by number and far more than that by length, concerned enslaved people. David Meade advertised “ABOUT one hundred Virginia born NEGROES” for sale, including “some female house servants, a carpenter, and shoemaker.” Four described enslaved men who liberated themselves by running away from their enslavers, offering rewards for their capture and return. The advertisers enlisted the public in engaging in surveillance of Black men to determine if they matched the descriptions in the newspapers. John Hudson, for instance, pledged “FIVE POUNDS reward” to “Whoever takes up … and secures” a “mulatto man, named GABRIEL, aged 52 or 53 years,” who had “a free woman for his wife, who goes by the name of Betty Baines.” The other advertisement described “a negro man named Frank,” dressed like a sailor, “COMMITTED to the jaol of Surry county” two months earlier. Thomas Wall, the jailer, called on Frank’s enslaver, Walter Gwin of Portsmouth, to claim the enslaved man and pay the expenses of holding him and running the advertisement.

Such advertisements stood in stark contrast to news about the Revolutionary War and “EXTRACTS from a most excellent pamphlet, lately published, and addressed to the Americans, entitled COMMON SENSE” that appeared elsewhere in that edition of Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette. William Rind founded that newspaper nearly a decade earlier, distributing the first issue shortly after the repeal of the Stamp Act. Eventually, Clementina Rind, his widow, published the newspaper and, following her death, Pinkney did so on behalf of her estate and her children. During that decade, each of those printers published hundreds of advertisements about enslaved men, women, and children even as they circulated news about the imperial crisis and the first months of the Revolutionary War. Revenues generated from advertisements about enslaved people underwrote newspaper coverage of current events and editorials about freedom and liberty.