What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

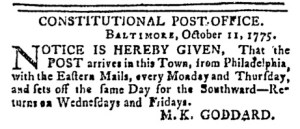

“CONSTITUTIONAL POST-OFFICE. BALTIMORE.”

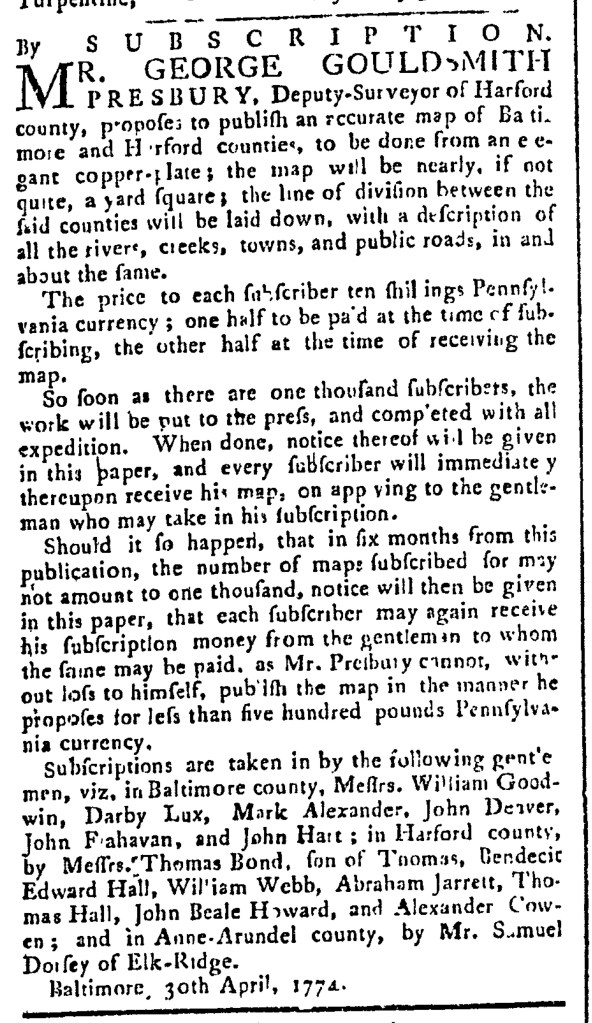

The contents of the October 11, 1775, edition of the Maryland Journal were organized such that the first advertisement that readers encountered promoted the Baltimore branch of the “CONSTITUTIONAL POST-OFFICE” established by the Second Continental Congress as an alternative to the imperial postal system operated by the British government. It completed the middle column on the third page, a column otherwise filled with news from Cambridge, Hartford, New York, and Philadelphia. Two lines separated it from other content, indicating a transition from news to advertising, yet the notice seemed a continuation of updates about current events, including an inaccurate report that General Richard Montgomery had captured Montreal as part of the American invasion of Quebec. Advertisements inserted for other purposes, such as fencing lessons and descriptions of runaway indentured servants, appeared in the next column and on the next page.

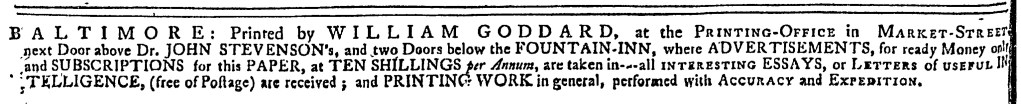

“NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN,” the advertisement proclaimed, “That the POST arrives in this Town, from Philadelphia, with the Eastern Mailes, every Monday and Thursday, and sets off the same Day for the Southward.” It returned from that direction on Wednesdays and Fridays. The notice was signed, “M.K. GODDARD.” The colophon at the bottom of the final page also listed “M.K. GODDARD, at the PRINTING-OFFICE in MARKET-STREET” as the printer of the Maryland Journal. Mary Katharine Goddard operated the printing office in Baltimore. Like many other printers, she simultaneously served as postmaster. Many of them, as Joseph M. Adelman explains, had been “associated with the old imperial system” and “shifted [their] service from the British post office to the American one.” They included Solomon Southwick, the printer of the Newport Mercury, John Carter, the printer of the Providence Gazette, and Alexander Purdie, the printer of the Virginia Gazette. Appointed to the position in 1775, Goddard served as postmaster in Baltimore for fourteen years “until she lost her position in 1789 to a new postmaster more closely connected to the new Federal Postmaster General.”[1]

Women participated in the American Revolution in many ways. They signed nonimportation agreements and made decisions in the marketplace that reflected their political principles, they spun wool and made homespun garments as alternatives to British imports, and they raised funds to support the Continental Army. Some served in more formal roles, including Mary Katharine Goddard as both the printer of the Maryland Journal and the postmaster at the “CONSTITUTIONAL POST-OFFICE” in Baltimore.

**********

[1] Joseph M. Adelman, “‘A Constitutional Conveyance of Intelligence, Public and Private’: The Post Office, the Business of Printing, and the American Revolution,” Enterprise and Society 11, no. 4 (December 2010): 742.