What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The GRAND AMERICAN CONTINENTAL ASSOCIATION … to be pasted up in every Family.”

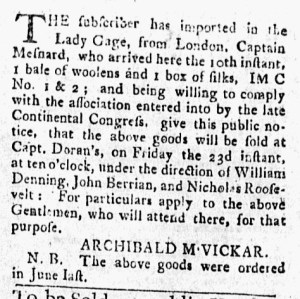

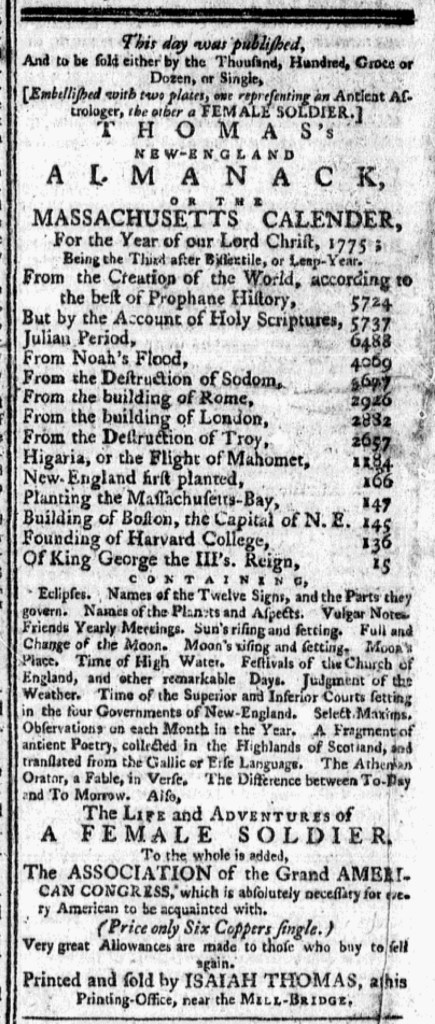

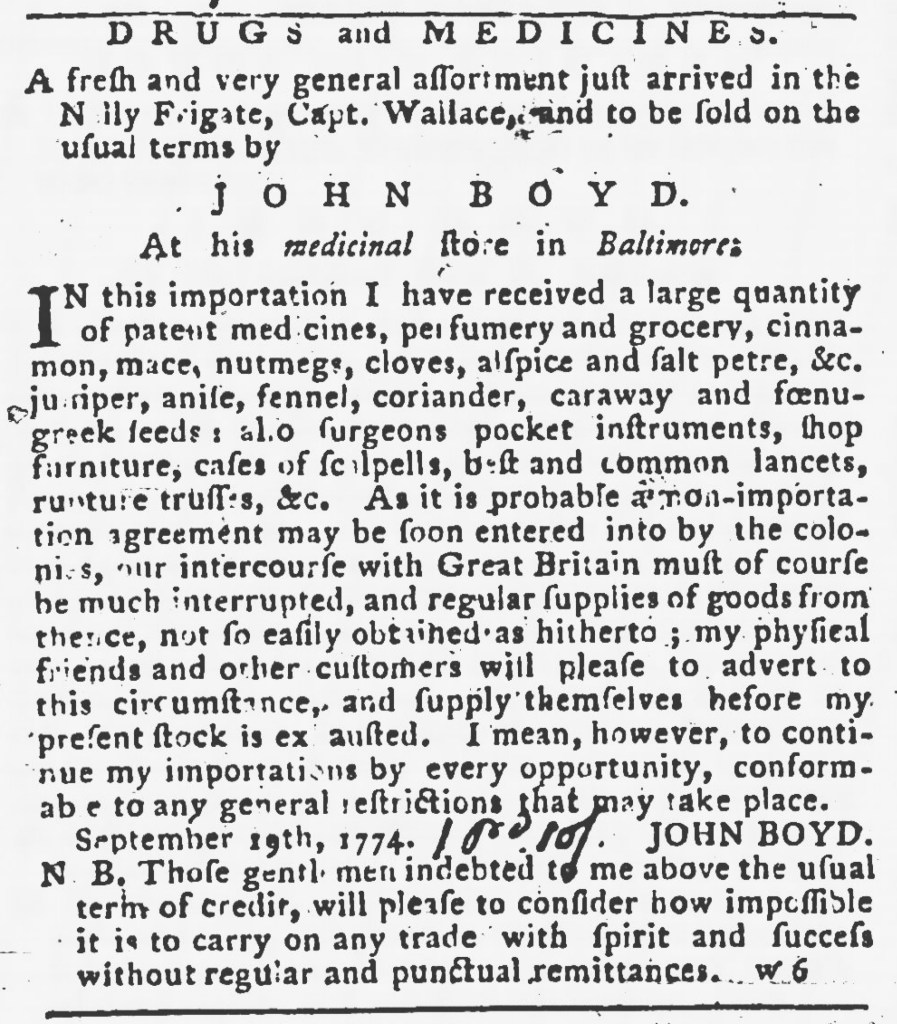

In the first issue of the Boston-Gazette published in 1775, Benjamin Edes and John Gill, the printers, opened with a notice concerning the Continental Association as the first item in the first column on the first page. The First Continental Congress had devised that nonimportation, nonconsumption, and nonexportation pact when it met in Philadelphia in September and October 1774, intending for it to go into effect on December 1. The Continental Association answered the Boston Port Act, the Massachusetts Government Act, and the other Coercive Acts that Parliament had passed in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party, perhaps not expecting a unified response from the colonies. The First Continental Congress, however, devised a plan that allowed consumers from New England to Georgia to express their political principles through the decisions they made in the marketplace., drawing inspiration from the nonimportation agreements that went into effect to protest the Stamp Act and the duties on imported goods in the Townshend Acts.

Edes and Gill helped to raise awareness of the Continental Association not only through newspaper coverage but also by disseminating copies far and wide. “ANY Town or District within this Province,” their notice advised, “may be supplied by Edes and Gill, on the shortest Notice, with the GRAND AMERICAN CONTINENTAL ASSOCIATION, printed on one Side of a Sheet of Paper.” They offered the pact as a broadside “on purpose to be pasted up in every Family.” The printers wished for local governments to purchase their edition of the Continental Association and distribute them to households for constant reference. Putting the pact on display demonstrated support for the American cause against Parliament or at least signaled an intention to comply. Posting it in homes as well as public spaces made it easy to consult, reminding everyone that they had a part to play in the protest. The Continental Association made decisions about participating in the marketplace inherently political, making it impossible for any individual or household to take a neutral stance. Edes and Gill recognized that was the case. Although they stood to generate revenue from selling broadside copies of the Continental Association by the dozen or gross, the political stance they consistently advanced throughout the imperial crisis suggested that increasing awareness of the pact and encouraging compliance with it motivated them as much or even more.