What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

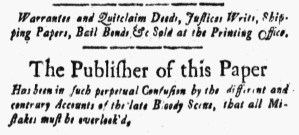

“Warrantee and Quitclaim Deeds, Justices Writs, Shipping Papers, Bail Bonds, &c Sold at the Printing Office.”

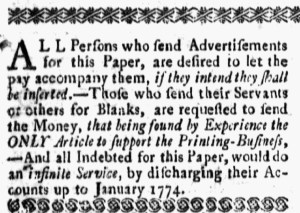

Daniel Fowle, the printer of the New-Hampshire Gazette, managed to keep publishing his newspaper after the battles of Lexington and Concord, though he warned readers that they could not depend on him doing so. On April 28, 1775, just over a week after the battles, he asked for those who owed money to settle accounts. “The Boston News Papers we hear are all stopt, and no more will be printed for the present,” Fowle noted, “and that must be done here unless the Customers attend to this call.” Two weeks later, he stated, “The publisher of this Paper Designs, if possible, to continue it a while longer, provided the Customers who are in Arrear pay off Immediately, to enable him to purchase Paper.” Fowle asserted that he had to price paper “at a great Distance and Charge.” Disruptions in his paper supply and “the disorder’d State of the Continent” (as Fowle described the aftermath of the battles at Lexington and Concord) led him to reduce the size of many issues to two pages instead of the usual four.

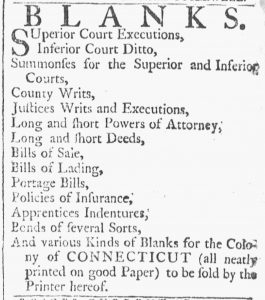

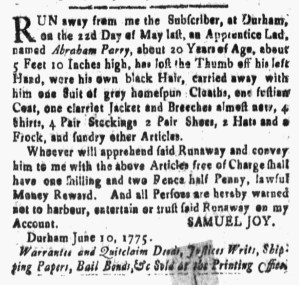

The June 27 edition was one of those, the third consecutive one. Fowle squeezed in as much news as he could, including updates from the Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in Watertown, and the New Hampshire Provincial Congress in Exeter. He also published an account of the Battle of Bunker Hill that occurred ten days earlier. The printer found one space for a couple of advertisements, including one that described Abraham Parry, an apprentice who ran away from Samuel Joy of Durham on May 22. The young man took advantage of the “disorder’d State” to get away from his master, though Joy offered a reward to “Whoever will apprehend said Runaway and convey him to me.” As the very last item on the second (and final) page, Fowle inserted an advertisement, just two lines, for printed blanks: “Warrantee and Quitclaim Deeds, Justices Writs, Shipping Papers, Bail Bonds, &c Sold at the Printing Office.” Such notices often appeared in newspapers during the era of the American Revolution, perhaps more frequently in the New-Hampshire Gazette than most others, because printers sought to diversity their revenue streams. Many of them printed and sold “blanks,” blank forms used for common legal and commercial transactions. In this instance, Fowle did not have enough space to insert a line to separate his notice from the advertisement above it, though he did use italics to distinguish it from Joy’s notice. More than ever, the printer needed whatever revenue he could get. He made sure to remind readers that he stocked and sold blanks.