What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

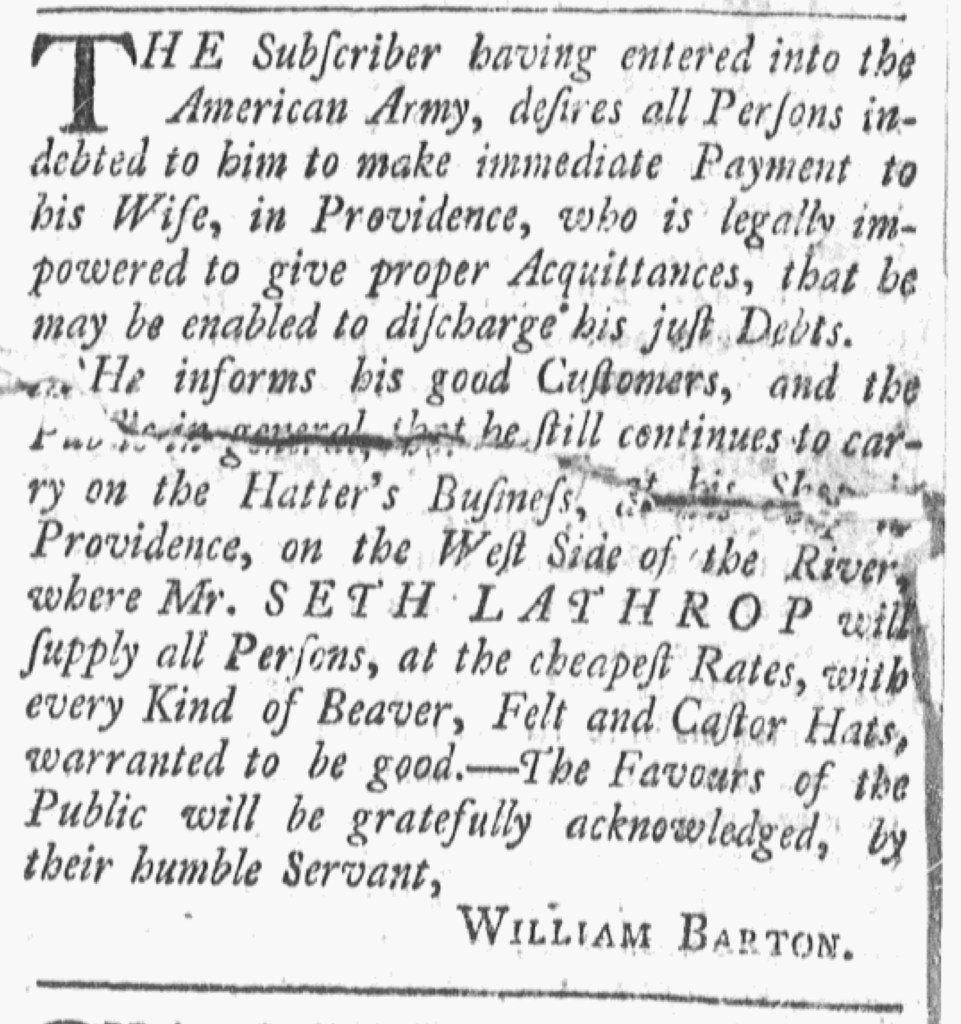

“THE Subscriber having entered into the American Army, desires all Persons indebted to him to make immediate Payment to his Wife.”

When William Barton, a hatter in Providence, “entered into the American Army” in 1775, he ran a newspaper advertisement that delegated responsibilities to his wife and a business associate. He requested that “all Persons to indebted to him … make immediate Payment to his Wife, … who is legally impowered to give proper Acquittances, that he may be enabled to discharge his just Debts.” It may not have been the first time that his unnamed wife oversaw accounts for the Barton household and her husband’s shop. Like many other wives of shopkeepers and artisans, she could have had experience assisting her husband by tending to customers while he was busy or away from the shop. She did not, however, assume responsibility for making sales during her husband’s extended absence while he served in the Continental Army, at least not initially.

Instead, Barton “inform[ed] his good Customers, and the Public in general, that he still continues to carry on the Hatter’s Business, at his Shop … where Mr. SETH LATHROP will supply all Person … with every Kind of Beaver, Felt and Castor Hats.” Barton did not indicate whether Lathrop previously played a role in the business. Had Lathrop been an employee or an apprentice who now ran the shop while Barton was away? Did he take new orders and make new hats according to the tastes of Barton’s “good Customers” and new clients who responded to the advertisement? Or did he merely sell hats already in stock when Barton enlisted in the army? Barton’s notice did promise low prices, “the cheapest Rates,” and made assurances about the quality of the hats available at the shop, proclaiming that they were “warranted to be good.”

Barton also declared, “The Favours of the Public will be gratefully acknowledged, by their humble Servant.” Although he deployed language that often appeared in newspaper advertisement to conclude his notice, he may have intended that his introduction would entice both his existing “good Customers” as well as new customers to support his business and, in doing so, his wife and their household. Barton likely hoped to leverage his service in the “American Army” as a selling point for his hats. After all, he chose to disclose that information first, making sure that it framed the overview of his shop that remained open during his absence. Some advertisers espoused support for the American cause in their newspaper advertisements. More significantly, Barton demonstrated his commitment to his political principles through his enlistment. That merited special consideration for his “Hatter’s Business, at his Shop” that remained open in Providence.