What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

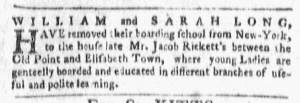

“WILLIAM and SARAH LONG, HAVE removed their boarding school from New-York.”

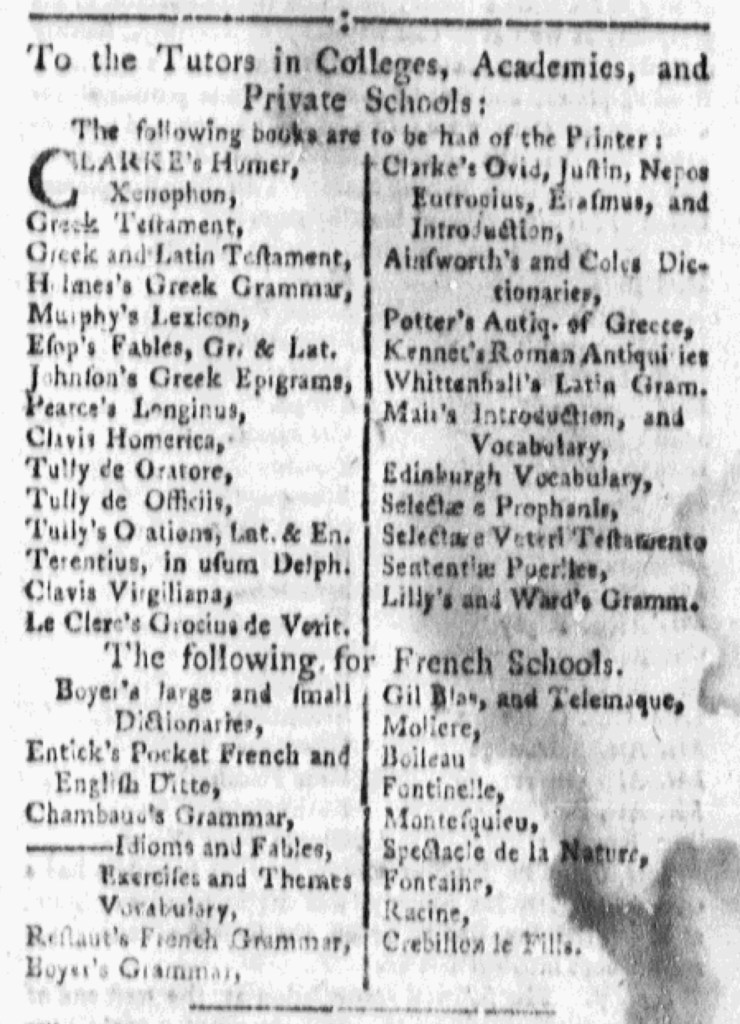

Late in November 1775, William and Sarah Long placed an advertisement for their boarding school “where young Ladies are genteelly boarded and educated in different branches of useful and polite learning” in the final edition of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, though they did not know that it would be the last issue. They advised prospective students and their parents that they “removed … from New-York, to the house late Mr. Jacob Rickett’s between the Old Point and Elisabeth Town” in New Jersey. What prompted the Longs to relocate outside the city? With the siege of Boston continuing, the uncertainty of where and when British soldiers would attempt to assert their authority likely played a role in their decision. A few months earlier, Andrew Wilson ran an advertisement for his grammar school in Morristown, New Jersey, emphasizing its distance from the coast. He invoked the “dangerous and alarming times [for] the inhabitants of large cities” and suggested that they “may wish to have their children educated in the interior parts of the country, at a distance from probable, sudden danger and confusion.” Similar thoughts may have inspired the Longs when they “removed” their school from New York.

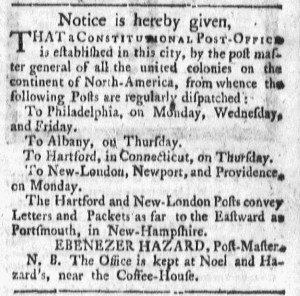

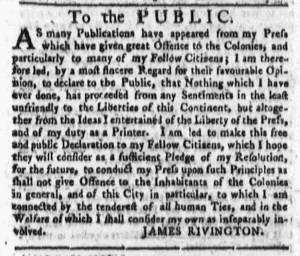

On November 27, “sudden danger and confusion” did indeed occur at James Rivington’s printing office on Hanover Square. Angry with the Tory perspective that Rivington often expressed in his newspaper, the Sons of Liberty attacked his printing office. It was not the first time, but the damage was much more significant than the previous attack. The Sons of Liberty destroyed Rivington’s press and type, preventing him from continuing to publish his newspaper or anything else. The printer decided to leave the city, sailing for London. He returned in 1777, during the British occupation of New York, and established Rivington’s New-York Gazette. It continued the numbering of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. That tile lasted for only two issues before he updated it to Rivington’s New York Loyal Gazette for several weeks and then the Royal Gazette throughout the remainder of the war. Rivington’s newspaper changed names one more time, becoming Rivington’s New-York Gazette for just over a month before ceasing publication with the December 31, 1783, edition. In his History of Printing in America (1810), patriot printer Isaiah Thomas noted that “for some time Rivington conducted his paper with as much impartiality as most of the editors of that period.”[1] Adhering to that impartiality longer than other printers contributed to the perception that Rivington favored Tory sentiments when he claimed that he merely exercised freedom of the press. Earlier in 1775, he advertised “Pamphlets published on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.” In addition to the Longs’ advertisement about their boarding school, the final issue of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer also carried an advertisement for the Constitutional Post Office in New York. The Second Continental Congress authorized the Constitutional Post as an alternative to the imperial system.

William and Sarah Long and their students “removed” from New York before “sudden danger and confusion” found them. James Rivington, on the other hand, fled the city after repeated attacks on his printing office made it impossible for him to continue printing his newspaper.

**********

[1] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 511.