What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“A SERMON on the present Situation of American Affairs.”

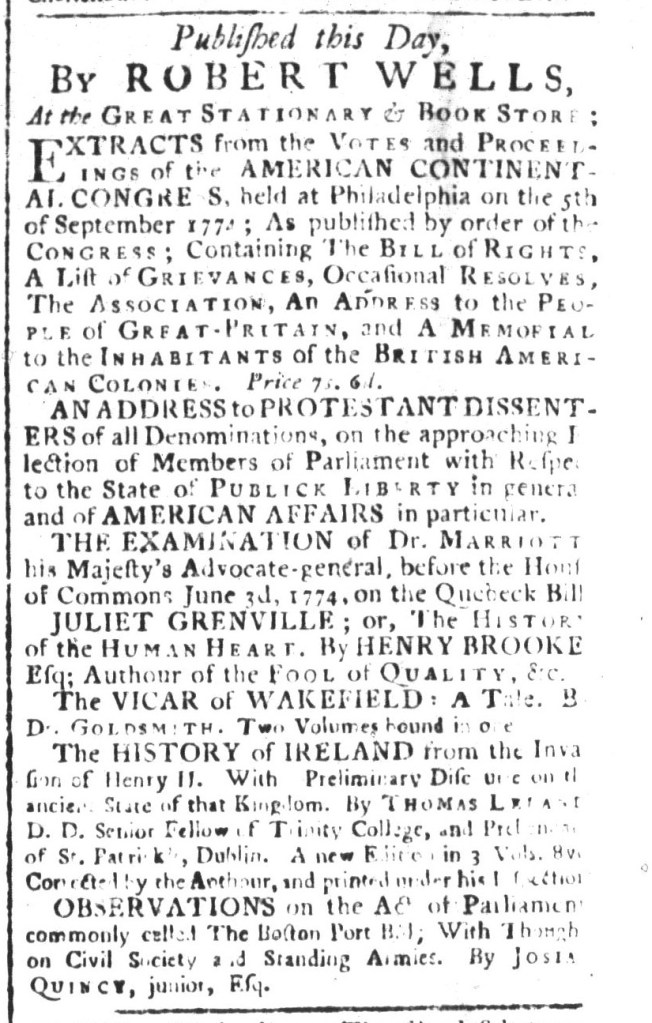

Robert Wells, the printer of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, often inserted advertisements that promoted the merchandise available at his “GREAT STATIONARY & BOOK STORE” in Charleston. On July 21, 1775, he devoted a notice to “A SERMON on the present Situation of American Affairs. Preached in Christ Church, Philadelphia, June 23, 1775, at the Request of the Officers of the Third Battalion of the City of Philadelphia and District of Southwark. By WILLIAM SMITH, D.D. Provost of the College in that City.” Like many other advertisements for books, the copy replicated the title page. Wells added the verse from the Book of Joshua that Smith cited as inspiration for the sermon.

The headline for the advertisement declared, “Just published, and to be sold BY ROBERT WELLS.” Did “Just published” and “to be sold” both describe Wells’s role in disseminating Smith’s sermon? When printers and booksellers linked those phrases together, they often meant that a work had been “Just published” by someone else and made available “to be sold” by other printers and booksellers. Wells may have acquired copies of the sermon printed by James Humphreys, Jr., in Philadelphia and retailed them at his own shop. Another advertisement in the same issue used the headline, “This Day are Published, BY ROBERT WELLS,” to introduce two books, “OBSERVATIONS on the RAISING and TRAINING of RECRUITS. By CAMPBELL DALRYMPLE, Esq; Lieutenant Colonel to the King’s Own Regiment of Dragoons,” and “THE MANUAL EXERCISE, with EXPLANATIONS, as now practised by The CHARLESTOWN ARTILLERY COMPANY.” In contrast to “This Day are Published,” other items certainly not printed by Wells appeared beneath a header that stated, “At the same STORE may be had.” On the other hand, Wells could have published a local edition of Smith’s sermon. James Adams printed and sold a local edition in Wilmington, Delaware.

Christopher Gould includes Smith’s Sermon on the Present Situation of American Affairs (entry 103) in his roster of imprints from Wells’s printing office, along with The Manual Exercise (entry 92) and Observations on the Raising and Training of Recruits (entry 93). For each of them, he indicates that he did not examine an extant copy but instead drew the information from newspaper advertisements. Gould explains that “many of the entries for 1774 and 1775 must be regarded as suspect. Wells advertises them as his publications, but in the absence of extant copies bearing his imprint, the likelihood is strong that they are in fact London editions of popular works bound in Charleston by Wells.”[1] As I have noted, Wells used a headline to introduce Smith’s Sermon that both contemporary printers and readers understood did not necessarily attribute publication to the advertiser. Even if he sold copies of the sermon printed elsewhere, they did not come from London. Smith delivered the sermon on June 23 and Wells advertised it just four weeks later, not nearly enough time for London printers to be involved. Wells advertised an American edition, even if he did not publish it.

Whatever the case, the sermon supplemented the news. Readers of the South-Carolina and American General Gazettefollowed all sorts of “AMERICAN INTELLIGENCE” from New England to Georgia, but the pages of any newspaper could present only so much content. Wells presented readers an opportunity to learn more about the discussions about current events taking place in Philadelphia by experiencing Smith’s sermon themselves. As consumers, they could become better informed and join with others who heard or read the sermon.

**********

[1] Chrisopher Gould, “Robert Wells, Colonial Charleston Printer,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 79, no. 1 (January 1978): 42.