What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

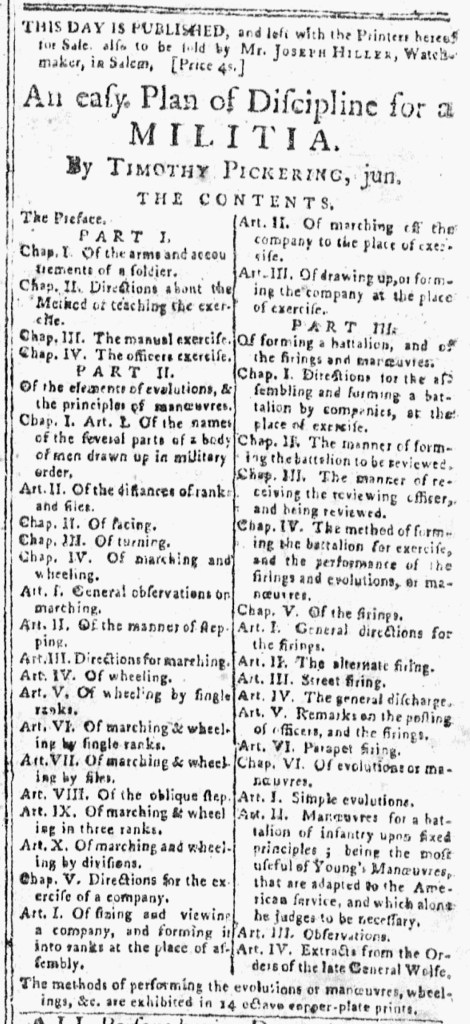

“An easy Plan of Discipline for a MILITIA. By TIMOTHY PICKERING.”

As the imperial crisis intensified when the Coercive Acts went into effect in 1774, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress recommended publication of a manual for training militia throughout the colony, The Manual Exercise as Ordered by His Majesty in 1764: Together with Plans and Explanations of the Method Generally Practis’d at Reviews and Field-Days. Over the next several months, several printers in New England published their own editions. Advertisements for The Manual Exercise appeared frequently in newspapers throughout the region. Printers beyond New England followed their lead. After the battles at Lexington and Concord, advertisements for other military manuals proliferated, including advertisements for Thomas Hanson’s Prussian Evolutions in Actual Engagements published by subscription in Philadelphia.

Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall, printers of the New-England Chronicle, published and advertised yet another military manual, An Easy Plan of Discipline for a Militia by Timothy Pickering, Jr. An advertisement for the work appeared in the July 27, 1775, edition of their newspaper. The Halls indicated that they had copies available at their printing office in Cambridge, where they had only recently moved from Salem and renamed and continued publishing the Essex Gazette. In addition, Joseph Hiller, a watchmaker in Salem, also sold the manual. The advertisement consisted primarily of an extensive list of the contents, demonstrating to prospective customers what they could expect to find in the volume, followed by a short note that the “methods of performing the evolutions or manœuvres, wheelings, &c. are exhibited in 14 octavo copper-plate prints.” The illustrations were an important addition that would aid readers in understanding the various maneuvers described in the book.

In addition to the advertisement the Halls inserted in the New-England Chronicle, Pickering pursued another means of marketing the book. He sent a copy directly to George Washington with a request that he consider “recommending or permitting its use among the officers & soldiers under your command.” Pickering flattered the commander of the Continental Army following his appointment to the post by the Second Continental Congress, declaring that the army had been “committed to your excellency’s care & direction” “to the joy of every American.” Pickering asserted his own “duty & inclination” inspired him to compose the manual and present it to the general for his consideration. He deemed it a “service [to] my country” that he hoped “may well prove advantageous in an army hastily assembled.” Washington did indeed take note. According to the American Revolution Institute, “Washington promoted the use of several published works, including Timothy Pickering’s An Easy Plan of Discipline for a Militia and Thomas Hanson’s The Prussian Evolutions” during the early years of the Revolutionary War. In 1779, Baron von Steuben’s Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States became the first official manual of the Continental Army. Until then, Pickering’s manual was a popular choice for training American soldiers.