What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“He has opened an AMERICAN PORTER HOUSE.”

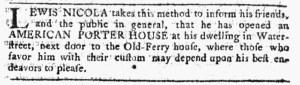

During the first week of 1776, Lewis Nicola took to the pages of the Pennsylvania Evening Post “to inform his friends, and the public in general, that he has opened an AMERICAN PORTER HOUSE at his dwelling in Water-street” in Philadelphia. He promised that “those who favor him with their custom may depend upon his best endeavors to please.

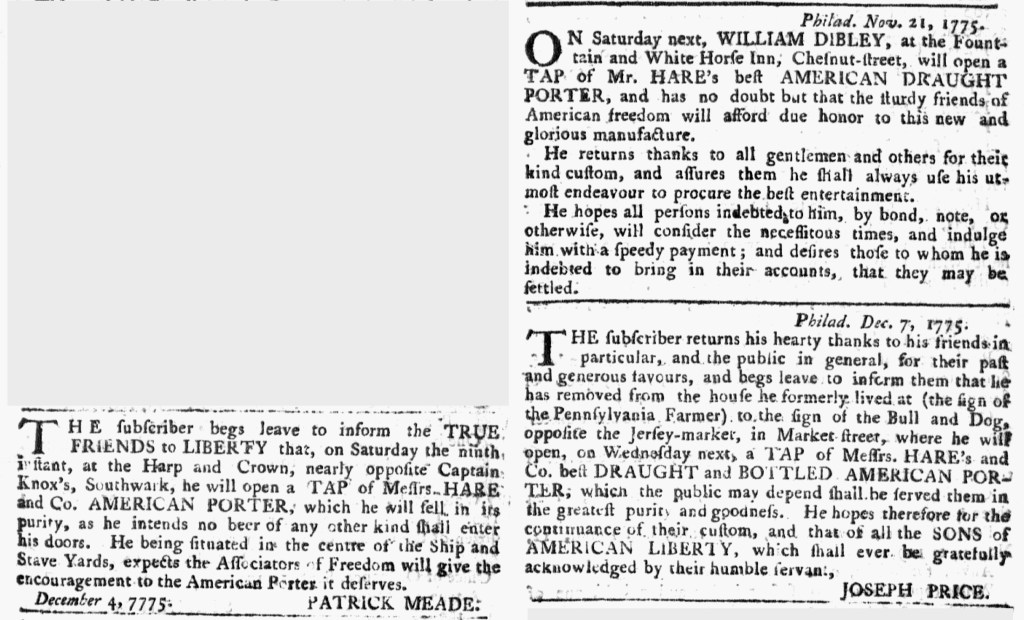

Nicola assumed that readers knew who brewed the porter that he served at his establishment. After all, “Mr. HARE’s best AMERICAN DRAUGHT PORTER” had been the subject of several advertisements that recently ran in the Pennsylvania Evening Post. William Dibley served “this new and glorious manufacture” at the Fountain and White Horse Inn on Chestnut Street. Joseph Price encouraged “all the SONS of AMERICAN LIBERTY” to drink “Messrs. HARE’s and Co. best DRAUGHT and BOTTLED AMERICAN PORTER” at his tavern “at the sign of the Bull and Dog” on Market Street. Similarly, Patrick Meade offered “Messrs. HARE and Co. AMERICAN PORTER” to “the TRUE FRIENDS to LIBERTY” at the Harp and Crown in nearby Southwark.

Robert Hare, the son of an English brewer who specialized in porter, arrived in Philadelphia in 1773. He established his own brewery where he brewed porter, “the first person to brew the drink in America.” The timing worked well for Hare; he commenced brewing American porter as the imperial crisis intensified and the Revolutionary War began. Colonizers looked to support local enterprises by purchasing “domestic manufactures” while they boycotted goods imported from England. That positioned Hare’s brewery for success.

Just as significantly, consumers liked his porter (unlike some of the substitutes for imported tea that some colonizers concocted). When John Adams attended the First Continental Congress in the fall of 1774, he lauded Hare’s porter in a letter to Abigail: “I drink no Cyder, but feast upon Phyladelphia Beer, and Porter. A Gentleman, one Mr. Hare, has lately set up in this City a Manufactory of Porter, as good as any that comes from London. I pray We may introduce it into the Massachusetts. It agrees with me, infinitely better than Punch, Wine, or Cyder, or any other Spirituous Liquor.” With Hare’s porter having such a reputation, Nicola did not need to mention the brewer when he opened his “AMERICAN PORTER HOUSE.” The public knew the porter came from Hare’s brewery.