What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“HARE’s and Co. best DRAUGHT and BOTTLED AMERICAN PORTER.”

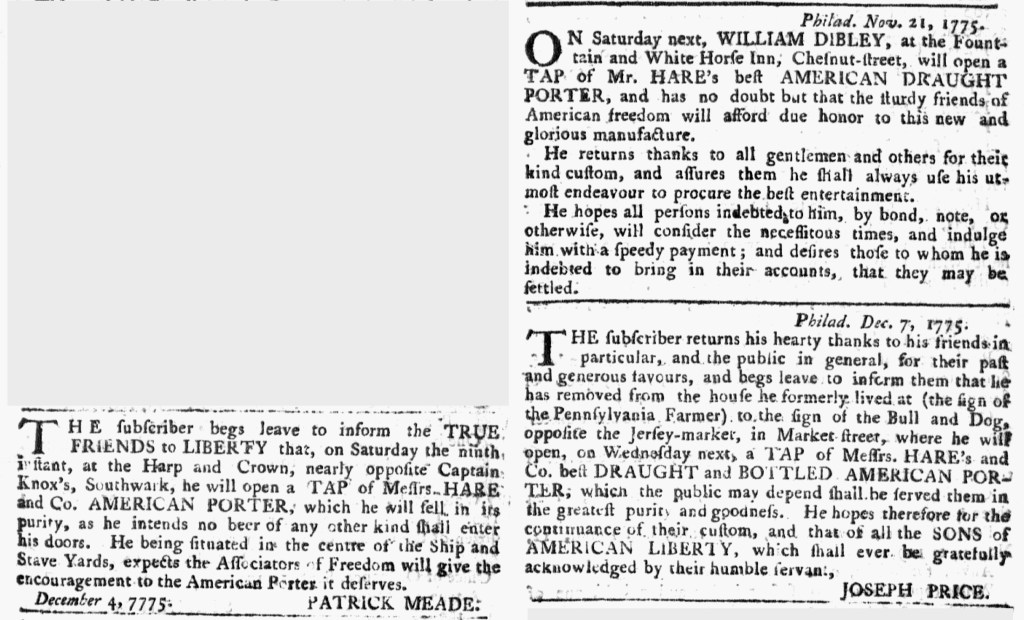

In December 1775, Philadelphia tavernkeeper Joseph Price ran an advertisement to express his gratitude to “his friends in particular, and the public in general,” while simultaneously alerting them that he had moved to a new location. They could now find him at “the sign of the Bull and Dog” on Market Street rather than at “the sign of the Pennsylvania Farmer.” To entice readers to visit his new location, he announced that “he will open … a TAP of Messrs. HARE’s and Co. best DRAUGHT and BOTTLED AMERICAN PORTER, which the public may depend shall be served them in the greatest purity and goodness.”

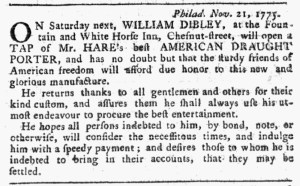

Price was not the only tavernkeeper promoting Hare and Company’s American porter, nor was he the only one associating that beer with support for the American cause. He proclaimed that he “hopes … all the SONS of AMERICAN LIBERTY” would affirm their commitment by choosing Hare and Company’s American porter. Price joined two other tavernkeepers who already promoted that brew. All three of them placed advertisements in the December 12, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. William Dibley’s advertisement ran immediately above Price’s notice. He confidently declared that he “has no doubt but that the sturdy friends of American freedom will afford due honor to this new and glorious manufacture.” Immediately to the left of Price’s advertisement, Patrick Meade stated that he “expects the Associators of Freedom will give the encouragement to the American Porter it deserves.” Readers who did not know much about Hare and Company’s American porter encountered endorsement after endorsement, encouraging them to take note of a beer that local tavernkeepers promoted over any others. Tavernkeepers usually did not mention which brewers supplied their beer, making these advertisements even more noteworthy. For their part, Hare and Company did not need to do any advertising of their own when they had such eager advocates for their American porter encouraging the public to demonstrate their political principles through the choices they made when they placed their orders at taverns in Philadelphia and nearby Southwark.