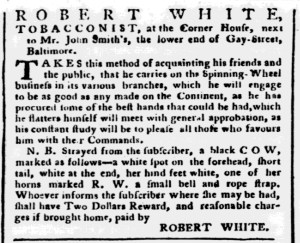

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He carries on the Spinning-Wheel business in its various branches.”

In the final weeks of 1775, Robert White, a tobacconist in Baltimore, diversified his business. He inserted an advertisement in the December 19 edition of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette that announced that “he carries on the Spinning-Wheel business in its various branches.” Why would a tobacconist decide to go into that line of business? The Continental Association, a nonimportation and nonconsumption agreement devised by the Furst Continental Congress, remained in effect. It called on colonizers to replace imported goods, including textiles, with alternatives produced in the colonies. That meant more time spent spinning, a domestic chore that gained political significance. Women styled Daughters of Liberty in newspaper accounts participated in public spinning bees to demonstrate their patriotism and inspire others to follow their example in their own homes. To do so, they needed the right equipment. White saw an expanding market for spinning wheels.

He was not alone in marketing equipment for producing homespun cloth. His advertisement happened to appear immediately above Fergus McIllroy’s notice promoting “LOOMS made properly, for carrying on the Linen and Woolen Weaving-business.” McIllroy, a “House Joiner,” also pursued a new line of work, though in his case doing so did not depart nearly as much from his primary occupation. In addition, he reported that he had previously constructed more than two hundred looms in Ireland before migrating to the colonies. White, the tobacconist, did not invoke such experience when it came to spinning wheels, yet he confidently proclaimed that he “will engage” his spinning wheels “to be as good as any made on the Continent” because “he has procured some of the best hands that could be had.” In turn, White “flatters himself” that his workers and the spinning wheels they produced “will meet with general approbation” or approval from customers. The tobacconist apparently served as a supervisor, an entrepreneur who established a business when he identified need for it during difficult time yet did not participate in making the spinning wheels. Instead, in overseeing his new business, he pledged that “his constant study will be to please all those who favours him with their Commands.” With no resolution in sight for the imperial crisis that became a war the previous April, White’s advertisement likely resonated with readers who understand the political implications of a tobacconist deciding to produce spinning wheels.