What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A neat Mezzotinto Print of the Hon. JOHN HANCOCK, Esq.”

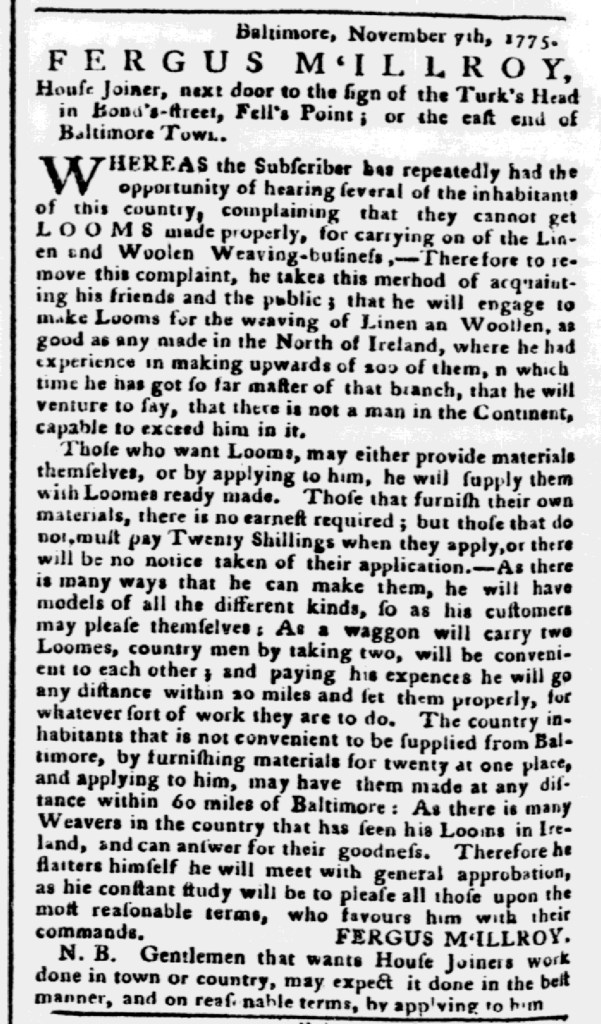

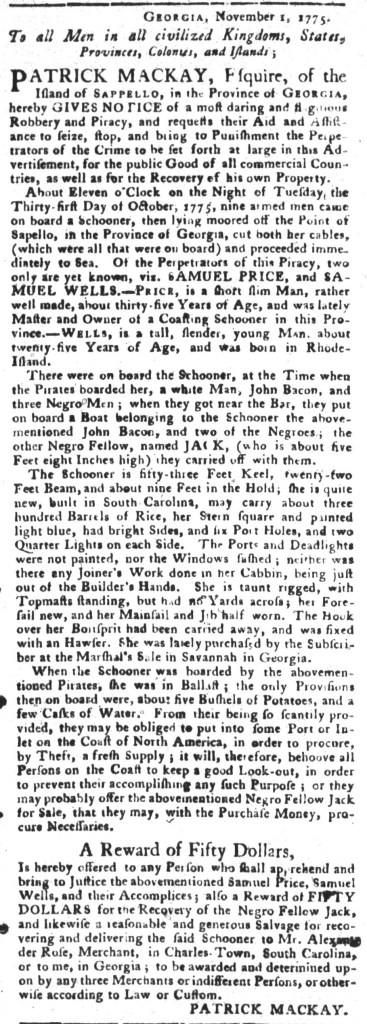

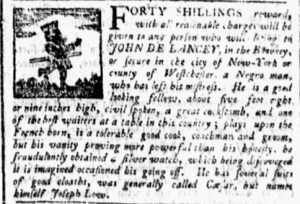

Richard Sause, a cutler in New York, became a purveyor of patriotic memorabilia during the Revolutionary War. In October 1775, he advertised “ROMAN’s MAP OF BOSTON,” billing it as “one of the most correct that has ever been published.” He described the cartographer, Bernard Romans, as “the most skilful Draughtsman in all America,” noting that he earned credibility because he “was on the spot at the engagements of Lexington and Bunker’s-Hill.” Nicholas Brooks, a shopkeeper who specialized in prints, and Romans collaborated on the project in Philadelphia. Sause acted as a local agent for marketing and distributing the map in New York.

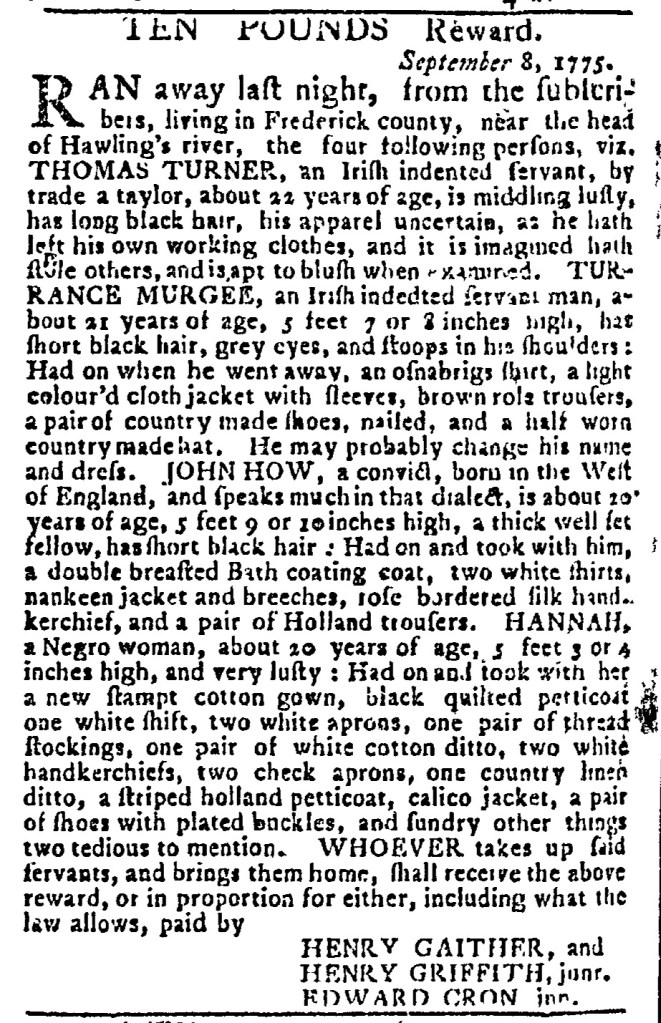

That was not the only item commemorating current events that Sause advertised and sold. At the end of November 1775, he took to the pages of the New-York Journal once again, informing the public that he sold a “neat Mezzotinto Print of the Hon. JOHN HANCOCK, Esq.” The print depicting the merchant from Boston who served as president of the Second Continental Congress was another one of Brooks’s projects. In addition, Sause also stocked “a view of the BATTLE at Charlestown” and “an accurate Map of the Present Seat of Civil War, taken by an able Draftsman.” Sause seemingly worked closely with Brooks in acquiring the various prints and marketing them to patriots in New York, perhaps even providing him with advertising copy to adapt for his own notices. The prints that Sause offered for sale appeared in the same order in his advertisement in the New-York Journal that they did in Brooks’s advertisement in Pennsylvania Journal. Brooks may have sent a clipping along with the prints that he dispatched to the cutler in New York.

Although Sause had established himself as a cutler who also sold hardware and jewelry in a series of advertisements in New York’s newspapers, his activities in the marketplace in 1775 emphasized his commitment to the American cause. Before he began selling prints, he promoted “SMALL SWORDS” to gentlemen who anticipated participating in the defense of their liberties and their city. Even though he continued to advertise an “assortment of Jewellery, Cutlery, Hardware, and Haberdashery,” he made items related to the conflict with Parliament and British troops quartered in the colonies the focal point of his advertisements.